The secret police organisations that arbitrarily seized and used for their own purposes the published and manuscript writings of oppositional intellectuals of the communist era paradoxically became the most committed preserver of the memory of cultural opposition in Romania. Today this material is kept by CNSAS in Bucharest; however, the size of these records on file makes them rather difficult to handle. After receiving in custody the documents of the former Securitate, the CNSAS archivists had to work out a new viable classification for the material they had been provided with, while keeping in mind that according to the Romanian Archival Law in force a given unit of documents cannot be decomposed and rearranged. Before 1989 the purpose of documents collected as a result of procedures labelled as inspection files was to punish, whereas according to today’s legislation in force the focus had to be placed on disclosure: the foundations of the lustration process had to be laid with the help of archival material. This has a separate administrative, judicial stage to it, a procedure that determines what role the person in question played in a given case. This is the context in which the archives of CNSAS in Bucharest must be placed: a physical space for storing all kind of Securitate files, including those pertaining to documentation, investigation, networking, observation, and other records. (István Bandi’s and Ladislau Antoniu Csendes’s statements).

The CNSAS archives in Bucharest house the Éva Cs. Gyimesi Collection, comprising 1,444 pages in six volumes. The records on file here can be divided in two categories. The first category contains documents compiled by the Securitate, archival materials related to Gyimesi that served the institutional purposes of the secret police. The second category comprises Gyimesi’s published writings, her memoranda addressed to the authorities, unpublished manuscripts, correspondence, documents originating from other private individuals that were collected and processed by Department I/B of the Department for State Security of the Ministry of Interior (DSS), responsible for Cluj-based Hungarian nationalists and also in charge of Gyimesi’s case. The subject of the various texts on file – reports, denunciations, action plans, shadowing reports, technical instructions, intercepted conversations and phone calls, letters, home search protocols, etc. – is “Csekéné Gyimesi Éva” (also named “Cseke Éva,” “Gyimesi Éva,” etc.), as well as persons she maintained more or less close contacts with (family members, friends, colleagues, allies, and other opposition members or collaborators in disguise).

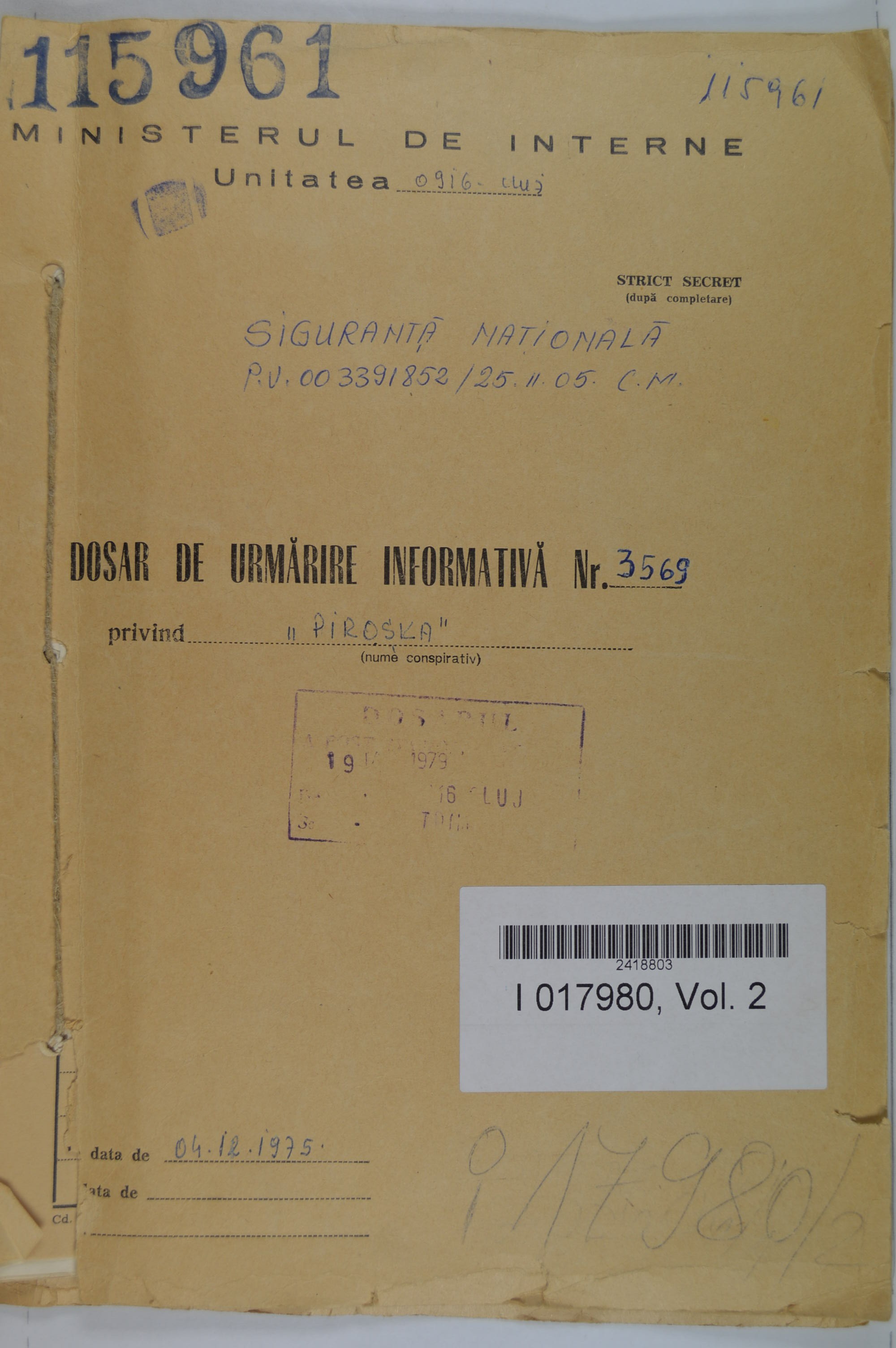

The files pertaining to the Informative Fonds cover events that took place between 1975 and 1989, and were regarded as of operative interest from the point of view of the secret police. They fit into the classification based on the “anti-regime, irredentist, nationalist” enemy image. In the case of Gyimesi, this documentation process lasted from the mid-1970s until the change of regime, but beginning with the mid-1980s a greater importance was attached to her case and it gained a higher value from the operational point of view. The files reveal to what extent the Securitate was able to get to know Gyimesi, how much effort was invested in her case, and how efficiently it acted against her. In this regard, beside Gyimesi’s teaching and lecturing activity, which was monitored as of 1976, there is information as to her being physically monitored in Bihor, Brașov, Covasna, Arad, Timiș, Sălaj, and Harghita counties, along with records of her permanent, almost daily monitoring between 1986 and 1989. The first observations were included in the file codenamed “Piroska,” and then the incoming materials were collected in a new file codenamed “Elena.” As of the second half of the 1960s, imprisonment as a result of declared “anti-regime” activity became outdated and prevention was placed in the foreground; the secret police planned to achieve this by means of warnings issued to the target person. Gyimesi received warnings in 1976, 1978, 1983, and again in 1985. Then, due to a failure to yield results and to radicalisation on the part of the target person as of the mid 1980s, the Securitate resorted to various methods of intimidation. The third, fourth, and fifth volumes of the file allow a better insight into the operational patterns of the system. Light is shed on the strategy that, beginning with the mid 1980s, the secret police used both informal collaborators and formal employees who were instructed by the liaison officer to mislead public opinion by compromising the target persons. This involved manipulating people whom Gyimesi respected and believed to be well-intentioned, in an attempt to make the target, Gyimesi, “more prudent” and more “self-contained”. This strategy included the dissemination of false information aimed at presenting Gyimesi as a Securitate informer. These files contain records relating to not only to Gyimesi’s oppositional manifestations and activity, especially from the second half of the 1980s, but also to Hungarian oppositional groups of the late communist period in Transylvania, from the samizdat Ellenpontok (Counterpoints) in 1981–1982 to the manifesto Kiáltó Szó (Screaming Word) in 1989. These files also illustrate the role private informers and professional agents had in the investigative actions taken against Gyimesi. The records also reveal that during the 1980s the secret police moved on to instruct university party leaders, party secretaries, and rectors in their investigative work against a member of the teaching staff of Babeș-Bolyai University in Cluj-Napoca. The translator of the manuscript of Pearls and Sand, confiscated on the occasion of home searches conducted in 1985 and 1989, belongs to the category of intellectuals in hierarchical positions who were also party members. This category included all those members of local power structures – such as party secretaries, heads of department, deans, rectors, etc.), who issued reports to the Securitate by virtue of their professional status, without signing any declaration of engagement, that is leaving no trace behind of their cooperation with the political police. The examination of the documents of the collection sheds light on the working instruments applied against the target group of “Hungarian irredentists,” which are, for the most part, identical to those used in dealing with leading representatives of religious minorities. (ACNSAS I017980/1-6).

The destiny of the collection was – to a certain extent – also influenced by the so-called “file-burning of Berevoiești.” In a press conference on 20 May 1991, Petre Mihai Băcanu, editor of the daily newspaper România Liberă, spoke about a large amount of Securitate files that had been buried. On 22 June 1990, thirty tonnes of documents were reportedly transported by the Romanian Intelligence Service (SRI) to the confines of the village of Berevoiești, close to Bucharest, where these records were buried in clay. Photos of the event were published in the daily paper Romániai Magyar Szó (Hungarian Word in Romania) and the weekly paper Valóság (Reality), as well as in most Romanian-language periodicals. These photos also show the name of Éva Cseke (Gyimesi) on the front page of one of the slightly scorched files in the ditch. The weekly paper Valóság published sequels of materials on the Hungarian persons involved, among others about Éva Cs. Gyimesi, Calvinist pastor László Tőkés, Géza Domokos, Károly Király, János Pusztai, Gábor Tőrös, Kálmán Zsuffa, Lajos Kuthy, Jenő Szikszay, and Roman Catholic priest Gábor Jakab at the end of the list.

After her files had been found “by accident,” Gyimesi entered into possession of a CNSAS-volume on 6 March 2006. Upon finishing her manuscript based on the materials of the first volume, she received a letter from the CNSAS informing her that further records relating to her person had been found. On 2 February 2009, Gyimesi examined a huge part of the newly discovered files in the CNSAS Archives in Bucharest. The texts of the first volume of files were identical to the materials of the file obtained in 2006. When reviewing the other five volumes she tried to focus on determining to what extent the material confirmed or refuted the hypothesis presented in her manuscript, so that she could turn down publication if appropriate; however, the records only served to confirm the message conveyed by her book. The story of the confrontation with the Romanian secret police files kept on her person is told by Gyimesi herself in her work entitled Szem a láncban: Bevezetés a szekusdossziék hermeneutikájába (Piece in a Chain: Introduction to the Hermeneutics of Securitate Files) which at the same time constitutes the most significant event of the collection (Cs. Gyimesi 2009).