The case of Gheorghe Muruziuc is somewhat atypical compared with the usual pattern of opposition to the Soviet regime, and all the more fascinating for this reason. Muruziuc was a person of working-class background, with no previous history of “anti-Soviet” activity. His main act of defiance consisted of raising the Romanian tricolour flag over a sugar factory in Alexăndreni, Lazovsk District (now Sângerei District), on 28 June 1966, i.e. on the twenty-sixth anniversary of the annexation of Bessarabia by the Soviet Union. The initial impetus for his rebellious act seems to have come from a blend of social dissatisfaction (couched in ethnic terms) and an acute sense of inequity, which his investigators at the KGB noted as a dominant character trait. At some point in 1965, he came into conflict with the factory administration. This conflict was mostly due to the fact that the plant manager, Korobka, an ethnic Ukrainian, had brought a major part of the workforce from Ukraine and Russia and seemed to disregard or even “mistreat” the local workers. Muruziuc’s dissatisfaction led to his first (minor) act of dissent, which occurred in May 1965. On this occasion, Muruziuc sent a telegram directly to Brezhnev, in which he complained about certain irregularities and cases of mismanagement and abuse at the factory. As a result, he was reprimanded at a special meeting of the factory party cell, while his standing with the management deteriorated. Starting from March 1966, he began to express his dissatisfaction in ethnically based terms and openly voiced his opinions regarding the discrimination to which the “Moldavian nation” was subjected to by the dominant Russians. Muruziuc extrapolated from several incidents occurring at his factory and expressed increasingly radical opinions in several conversations held with a number of co-workers, friends, and acquaintances. Essentially, his views were that Bessarabia rightfully belonged to Romania and had been illegally annexed by the USSR in June 1940. Therefore, the policies pursued by the Soviet state were leading towards ethnic discrimination against the “Moldavian nation” and might result in the disappearance of Moldavian national culture, language, and customs. Muruziuc openly stated that the majority population of the MSSR had “much more in common, linguistically, culturally, and historically with the Romanians than with any of the other Soviet nationalities.” Obviously defying and rejecting the official Soviet doctrine of “friendship of the peoples,” Muruziuc advocated the secession of the MSSR from the USSR and its subsequent union with Romania, which he saw as the only way to preserve the Moldavians’ ethnic specificity and national culture. Interestingly, during his later interrogation by the KGB, he changed his position, arguing for the creation of an independent Moldavian state also comprising the Romanian region of Moldavia, although completely separate from the USSR. It is not clear what the reason for this change of opinion was. It led his KGB investigators to doubt his sanity, but was more likely caused by pragmatic considerations and the partial recognition of his “guilt.”

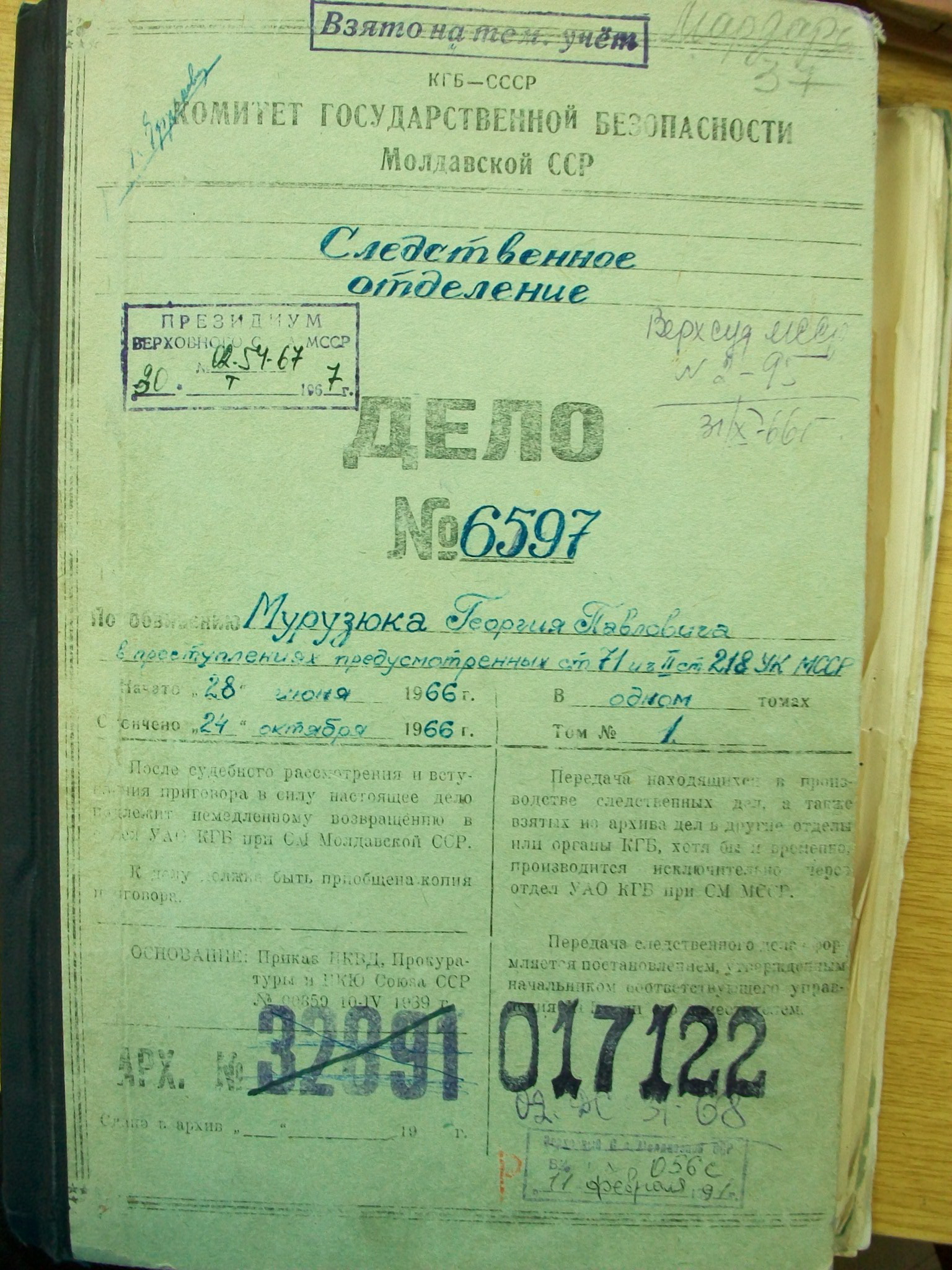

The current collection is part of the collection of judicial files concerning persons subject to political repression during the period of the communist regime that is currently stored in the Archive of the Intelligence and Security Service (SIS) of the Republic of Moldova. Muruziuc’s file was registered under No. 6597. The file was begun on 28 June 1966 (during Muruziuc’s interrogation) and finished on 24 October 1966 when the verdict was delivered. The file contains the following items: the decision concerning the opening of the criminal case against him (pp. 1–2), the decision concerning the searching of his house and the subsequent protocol (pp. 3–5); a letter confiscated from Muruziuc’s house, which he had written to Brezhnev in 1965 to complain about irregularities at the factory (p. 6–7); a brief report of the local KGB district officials and the testimonies of Muruziuc’s co-workers, which provided the essential details of the case (p. 8–10); the official file on Muruziuc compiled after his arrest (p. 12–13); various official procedural documents concerning the transfer of the trial from the jurisdiction of the prosecutor’s office to the KGB, given the nature of Muruziuc’s acts (pp. 14–18); detailed minutes of Muruziuc’s interrogations, which represent a substantial part of his file (pp. 19–81), detailed interrogation of witnesses with the aim of confirming or disproving Muruziuc’s testimonies, including his wife, various co-workers, friends, and acquaintances (pp. 82–210), the records of confrontations between Muruziuc and various witnesses in order to corroborate the existing evidence (pp. 211–35), the examination of incriminating evidence, including several photos of the flag made by Muruziuc (pp. 235–39, see Masterpiece 2); several papers related to the psychiatric report on Muruziuc’s sanity, including the official conclusion of the expert confirming the lack of any mental disorder (pp. 243–49); the official accusatory act concerning the case of Gheorghe Muruziuc (pp. 260–8) and, finally, the judicial decision rehabilitating Muruziuc, which the Moldavian Supreme Court adopted in March 1991 (pp. 338–44). For the purposes of this collection, the most important documents are those relating to Muruziuc’s testimony (which he confirmed by his own signature) and the incriminating material evidence, including photos of the flag, which was later destroyed by the KGB. The final accusatory act is also of some interest, since it provides a synthetic account of Muruziuc’s actions, his perceived motivations, and the official grounds for the accusation (see Masterpiece 1). Muruziuc’s testimony is revealing for the sources of his opposition to the regime. Even if his discontent was first formulated for purely material reasons, he gradually became aware of the national dimension of the injustice he perceived. Apparently his conversations with some of his more educated acquaintances and his reading of some “subversive” poems by classic Romanian writers were the direct incentives for his action.

Muruziuc’s case raises a number of questions, especially in view of his relatively mild punishment of only two years of forced labour. The leniency of his sentence is even more evident when compared to some later cases of “nationalist opposition” in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Apparently, the Soviet authorities did not wish to attract undue attention to the actions of someone they considered a “lone wolf.” Conversely, the attitude towards any organized opposition was much less tolerant, as was proven by the harsher punishments meted out for “nationalist propaganda” in the changed post-1968 context. Nevertheless, Muruziuc’s claim to represent the collective opinion of the “Moldavian nation,” however spurious, did raise concerns, as is shown by the trial files. At the same time, Muruziuc’s social background might have played a role. Most other cases featured intellectuals or people with an “unreliable” family history, whereas Muruziuc was a worker and came from a peasant milieu, while his siblings were thoroughly integrated into Soviet society. The importance of social status is also apparent when the authorities assessed the impact of Muruziuc’s ideas, clearing the two people most closely involved in his case (Trachuk, a policeman, and Scripcaru, a lawyer) of all charges, following a protest filed by Scripcaru in 1968.