Youth Subcultures Ad-hoc Collection at CNSAS

The Youth Subcultures Ad-hoc Collection at CNSAS comprises documents created or collected by the Romanian secret police, the Securitate, about the emergence and development of Western-inspired subcultures among the members of the younger generation in Romania, subcultures which the communist regime considered harmful for their education and whose influence it thus tried to counteract. This collection illustrates that young people even in an isolated country like Romania in the 1970s and the 1980s still became exposed via Western broadcasting agencies to Western cultural goods, especially to music, which made them adopt alternative life styles and wear provocative outfits in order to build distinctive collective identities. Out of the many young people who attracted the unwanted attention of the Securitate two cases stand out and are featured in this ad-hoc collection: Clubul Regilor Liberi (The Club of the Free Kings) in Brăila and Organizația Tinerilor Liberi (The Organisation of Free Young People) in Bistrița.

Location

-

București Strada Matei Basarab 55, Romania 030167

Show on map

Languages

- Romanian

Provenance and cultural activities

-

The Youth Subcultures Ad-hoc Collection at CNSAS reflects the cultural opposition of young people to the Romanian communist regime. They not only refused to obey the communist regime and its plans for the cultural and social uniformisation of its citizens but also sought and found in foreign music and musical subcultures an appealing way of asserting their identity and control over their free time. Of the five fonds of the archives of the former Romanian secret police, the Securitate, the documents of the Youth Subcultures Ad-hoc Collection can be found in three: the documentary, informative, and criminal fonds. For the Securitate, the beginning of the “youth problem” in relation to young people’s consumption of Western music related to two legal and ideological changes, which occurred at the beginning of the 1970s. First, Decree 153/1970 incriminating so-called “social parasitism” created the legal framework to harass those young people who refused to engage in “useful activities,” as the regime defined its educational activities, and preferred to spend their time according to their own ideas, not only in private places, but also in public spaces, such as parks, coffee shops, or cake shops, mostly listening to Western music and adopting obviously alternative and deliberately provocative outfits. The decree allowed the communist Militia to pick up young people in the streets and force them to cut their long hair and even to destroy their Western-inspired pieces of clothing, such as blue jeans or mini-skirts. Second, the so-called “Theses of July 1971,” which redefined the ideological tenets of the regime in the field of culture, also shaped the policy of the Securitate towards the younger generation. In July 1971, the Romanian state and party leader, Nicolae Ceaușescu, delivered a long speech in which he highlighted the need to improve the “political, ideological, and Marxist education” of all Romanian citizens. This was to be done by implementing a series of measures aimed at fostering the making of the “new man” whose ascribed role as the “builder of socialism” required a high level of consciousness. The arts, culture, and education were considered essential to this effect. Thus, they were not only to be subordinated to the political sphere and its ideological tenets, but they also needed to find sources of inspiration in contemporary Romanian realities. This change in cultural policy gradually led to severe limitations in the import of Western cultural products and the circulation of Romanian citizens across the Iron Curtain.

The files from the documentary fonds that the Securitate created under the label of “problem youth–education” (over 60 files) and “problem art–culture” testify to the interest shown by the communist authorities in the emerging Western-inspired youth subcultures, such as hippy, punk, new wave, and rock. In this context it should be mentioned that due to weak connections with the West, information about youth subcultures reached the communist countries with some delay. This is the reason why, for example, during the 1970s, many Romanian young people formed hippy groups at the moment when in the West this subculture had lost most of its appeal. Given the fact that Romanian youth stubbornly refused to comply with the new regulations about the banning of the consumption of Western cultural products, the Securitate tried to identify the sources from which the youngsters could find out about foreign music. As a result, a substantial part of the documents written by the Securitate’s county branches describe how young people, alone or in small groups, listened to foreign radio stations, such as Radio Free Europe (RFE), Voice of America, or Radio Luxembourg, in the safe comfort of their family homes, in school dormitories, or even at school parties. Relating to the activity of listening to foreign radio stations, the Securitate also collected information about the Romanian fans who wrote letters to the producers of Western radio programmes requesting that they air their favourite songs. In fact, writing this kind of letter was the main reason for which young people atracted the unwanted attention of the Securitate. Aware of the fact that their letters could not reach the destination by normal postal services, which were under strict surveillance, the young people identified and used alternative means to send their letters to foreign radio stations. Thus, the documents identify numerous cases of adolescents who managed to send their letters with the help of tourists, truck drivers, friends, foreign students, or relatives who travelled abroad and posted the letters from there.

According to Securitate estimations, there were three sources from which young people in Romania could inform themselves about Western youth subcultures. First, those young people who disregarded the official restrictions on Western music with which local radio stations had to comply recorded songs broadcast by foreign radio stations. Consequently, many documents identified individual cases of high-school pupils, students, and even workers who recorded foreign music on magnetic tapes or on cassettes and played them at small parties or lent them to their peers. Besides foreign radio stations, another way of gathering information about foreign music and musical subcultures was through travel abroad. Only a small proportion of Romanian young people could travel abroad because such trips were not only expensive, but also depended on the approval of an exit visa by the secret police. The Securitate documents record that these young people bought and smuggled into Romania vinyl discs, cassettes, and magazines, such as Bravo from the Federal Republic of Germany and Ifjúsági Magazin (Youth Magazine) or Világ Ifjúság (Youth of the World) from Hungary, attended concerts, or simply met up and became acquainted with hippy, punk, new wave, rock, or csöves (lit. “tubular” – a Hungarian subcultural movement) friends. On their return home, they began to express their allegiance to these subcultures by making changes to their appearance and behaviour that were quickly copied by their peers who had not had the chance to travel. Finally, the Securitate noted that the official media was another source of information for young people interested in musical subcultures. In fact, these media products such as television programmes or articles published in various magazines were highly critical and specifically designed to counter such tendencies, but young people selected and imitated precisely the highlighted “negative aspects” of the Western subcultures which the official media criticised (ANCSAS D 8833vol. 10, ff. 227 f–v, 262–262 f–v, 335–336, 441; vol. 11, ff. 23 f, 118 f–v; vol. 14, f. 300; vol. 15, ff. 211 f–v, 217f–v, 415–419; vol. 18, f. 318 f; vol. 25, f. 395; vol. 36, ff. 107–109; vol. 43, ff. 146–147; vol. 47, f. 342, 432; D 18306 vol. 7, f. 184 v; vol. 11, ff. 250–251).

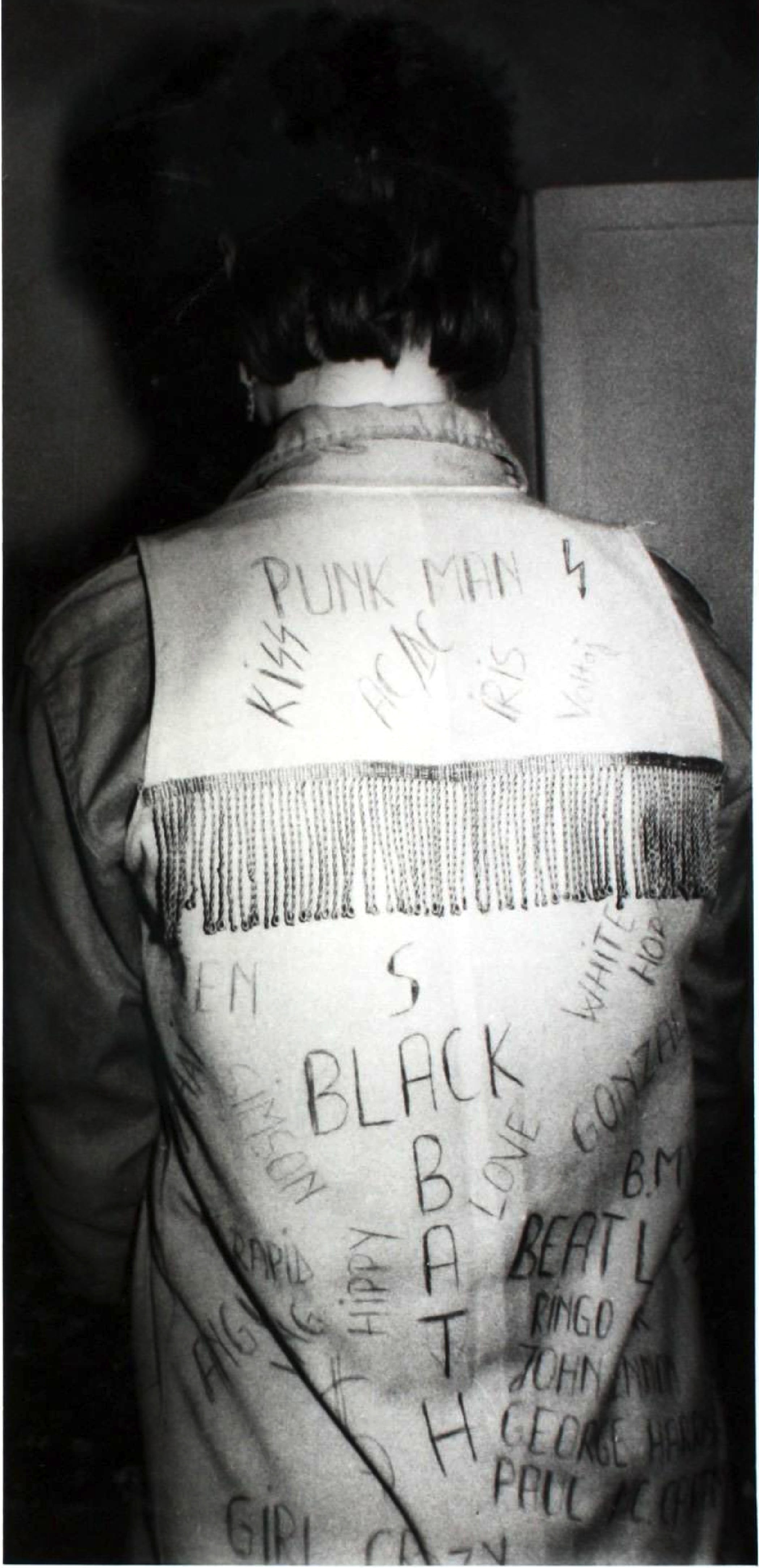

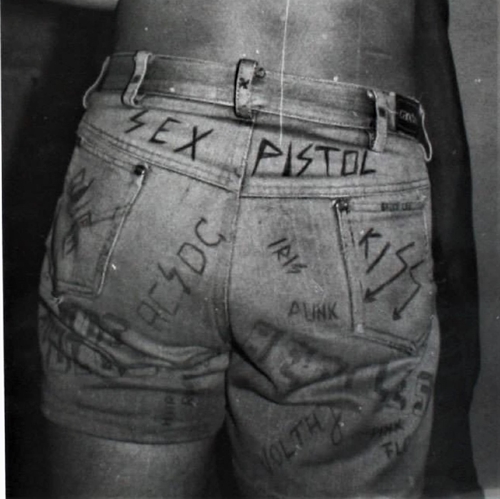

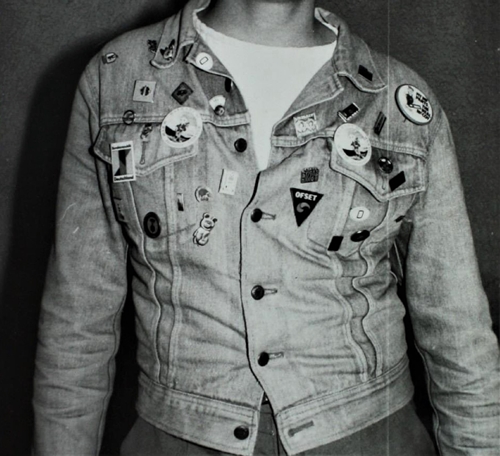

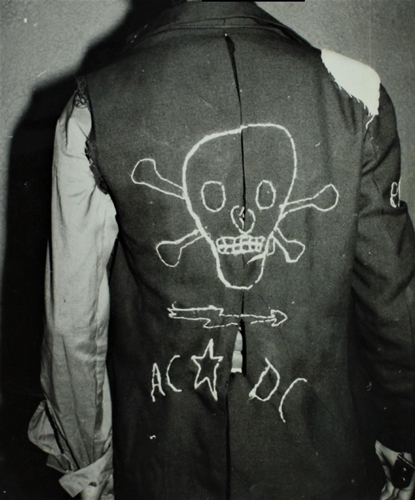

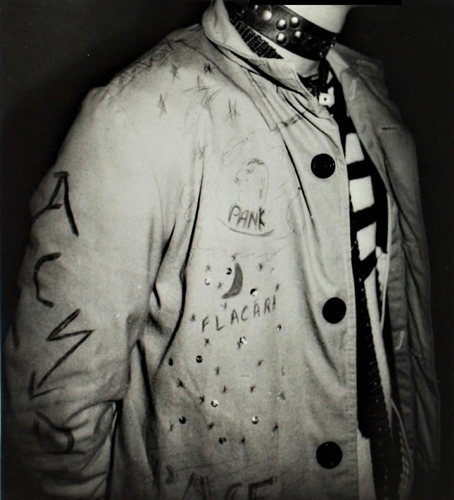

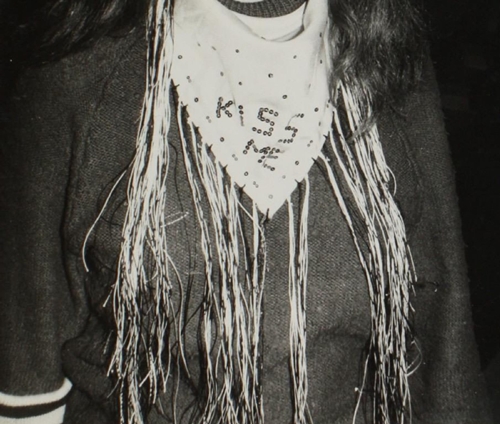

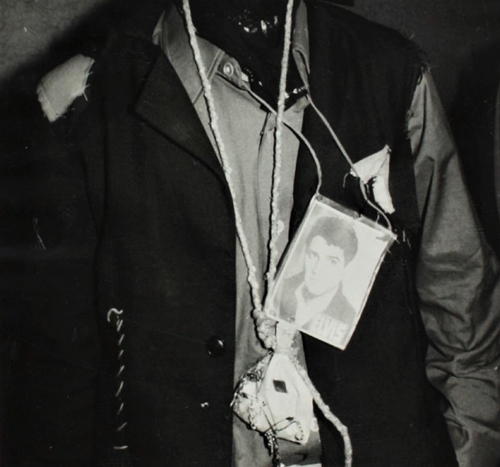

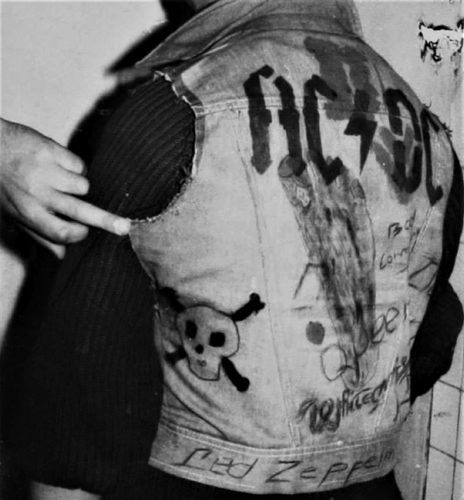

The Securitate even became interested in curtailing the private consumption of Western music once it observed that this resulted in changes in the behaviour and dressing style of the younger generation. Accordingly, many documents written by the Securitate’s county branches enumerate the negative consequences of listening to Western music broadcast by foreign radio stations. As registered by the secret police officers dealing with such issues, young people engaged in “tendentious comments, praising the capitalist way of life,” would “praise the freedom enjoyed by young people in the capitalist countries, [or] denigrate the social-political achievements of our country,” tried to cross the Romanian border illegally, or chose English names for themselves and their hippy, punk, or rock bands. The secret police documents painstakingly enumerate such nicknames as Michael Jackson, Rod Stewart, Fredy Mercur (sic!), Bruce Lee, King Fufu, King Arthur, Billy Boy, Dire Straits, The Club of the Free Kings, The Kid Klan, Punk, etc. It should be mentioned that the nicknames were used by these young people not only when interacting with each other but also when signing their letters to Radio Free Europe in hope of avoiding easy and immediate identification by the Securitate (ACNSAS, D 8833 vol. 50, f. 162 f; vol. 36, f. 107; vol. 11 f. 13; D 8687, ff. 54 v, 62, 64, 67, 69, 153; I 906390; I 3032 vol.1; I 855732 vol. 1). Apart from choosing English nicknames, the Romanian fans used bricolage and artefacts to imitate the subcultural styles using whatever was available. According to the secret police evaluation, punk fans opted for “eccentric outfit, clothes in strident colours” that they adorned with “large safety pins, fibulae, beads, badges, lacing, animal teeth” and preferred “T-shirts with bizarre animal figures and skulls, with chains and wires on which they had strung nuts and washers, etc. and wore them around their necks, with metallic clips and safety pins of unusual size” in order to create “a behaviour and an appearance out of the ordinary” (ANCSASfile D 8833 vol. 41, f. 68 f–v). In contrast, young new-wave fans dressed in “green shirts and wide-legged trousers,” or “white trousers and black underwear,” while “some shaved above the ears, with a Mohawk in the middle of the head, and the others combed with many partings or with hair falling over their eyes to the chin” (ACNSAS, D 8833 vol. 18, f. 4 f).In addition to the subcultures directly inspired from Western youth subcultures, the Securitate single out csöves, or “tubular,” a version of the punk subculture that developed in Hungary at the end of the 1970s (Ryback 1990, 171) and was subsequently adopted by Hungarians living in Romania. Despite their connection with punk subculture, the csöves in communist Romania, according to the description made by the secret police, wore outfits which were more typical of hippies: “tight pants, long and large shirts, overabundant hair, shoes with sharp edges” or “red ties with white dots, some rubber bracelets, blue jeans, T-shirts with different initials, etc.” Their outfits were, however, highly accessorised with “metal chains, ornaments made of razor blades, scallops, crosses, knives introduced in the loops of their clothes,” which were indeed specific to the punk subculture. Also, the csöves outfit was completed with adornments on their bodies that included “safety pins under their skin in the visible parts of their bodies: on hands, throat and face.” The greetings between csöves in Romania were made in Hungarian – “servus csü” (sic!) (hello tube!) or “elgen csü” (sic!) (long live the tube!) – and were accompanied by the specific gesture of raising the arm and forming a “V” shape with two fingers (ANCSAS D 8833 vol. 10, f. 343 f; vol. 11, f. 23 f–v; vol. 14, f. 322 f).

Apart from these descriptions of the subcultural styles adopted by the Romanian fans, the Securitate documents also contain assessments on the purpose of the musical subcultures. The starting point of their evaluations was the belief that Romanian punk, heavy metal, and new wave fans were driven by the same rebellious stance toward authority and the status-quo as their Western counterparts. As a result, the Securitate county officials looked for and recorded in their reports any signs of oppositional behaviour of the punks or csöves in Romania: “The young csöves and punk adopt a parasitic lifestyle, refuse to carry out socially useful activities, promote a strong maverick spirit, of parasitic type, wishing to live at the edge of so-called complete liberty; they enter into a moral conflict with their society and families; they indulge in antisocial actions; prone to violence, having a profound aversion towards everything that renders order and discipline in the society, some of them leave their homes, surviving on expedients, thefts, and begging; they wear clothes of tubular type, live under bridges and in sewerage pipes (hence the name csöves – tube people)” (ACNSAS, D 8833 vol. 14, ff. 322–323).

The Romanian secret police paid a special attention to what it identified as “youth entourages,” which mushroomed in Romania during the 1970s and 1980s. In fact, these “entourages” were informal gatherings that young people created for hanging out and listening to foreign music, usually broadcast by RFE. Thus, the local branches of the Securitate wrote reports about the many groups created by Romanian fans, in which they recorded the name of the groups, personal information about the founders of the groups, the members of the “entourages,” their behaviour and outfits. In this context, it is important to mention that in some cases the Securitate identified these young people based on the letters they sent to the Romanian department of RFE. Consequently, the Securitate officers explained the youngsters’ nonconformist and oppositional behaviour as resulting from their exposure to the musical programmes of RFE. The fact that the members of the groups strove to build a distinct identity for themselves based on their allegiance to one of the musical subcultures was a constant source of worry for the Securitate. Thus, its officials thoroughly record in their reports that members of groups such as Kid Klan, Instigatorii (Instigators), Victory Organisation-1971, Uniunea Forțelor Disco (The Union of Disco Forces), Discomanii (Discomaniacs), etc. openly express their allegiance to hippy, punk or rock subcultures, that they hang out in specific places (parks, discotheque, bars, cake shops), and distinguish themselves from their peers by wearing distinctive signs imprinted on T-shirts, insignia, or badges (ACNSAS, D 8833 vol. 25, ff. 279–280; vol. 11, f. 118 f–v; vol. 15, f. 217 f–v; D 13365 vol. 1, ff. 116, 38).

The secret police reports also mention the measures taken by various local branches against these subcultural groups. In most of the cases, action was limited to breaking up the “entourages” by resorting to warnings, public debates, and so-called “positive influencing measures.” Consequently, many reports briefly describe the meetings between a young person and Securitate officers at local headquarters, usually ending when the former “fully admitted and apologised for his deeds, and made a written commitment not to engage in similar types of behaviour in the future.” In other cases, the Romanian secret police with the help of officials from the local youth organisation or from the high-school or factory administration organised public debates. During these meetings, the behaviour of the young person found guilty, for example, of being “an admirer of punk” was publicly incriminated as “anti-social and potentially harmful” to the general interests of Romanian society. The reports of the Securitate also included references to how the network of informers, family members, and educational agents was used to “positively influence” the young person or to deter them from further embracing behaviour specific to an alternative subculture (ACNSAS, D 8833 vol. 10, ff. 335–337; vol. 11, f. 23;vol. 43, ff. 143, 146–147; vol. 45, f. 427v; D 12550 vol. 1, f. 9 f–v; D 13365 vol. 1, ff. 38–39, Ţârău 2009, 64).

In most cases the warning, public debate, or positive influencing measures put an end to young people’s encounters with the Securitate. In other cases, the surveillance continued but soon ended when the Romanian secret police was sure that the youngsters had abandoned their public allegiance to the respective subculture. However, there were cases when the Securitate opened a file of informative surveillance on the name of the members of a hippy, punk, or rock group and some of these young people even received prison sentences for their daring act of opposing the communist regime culturally. Among the many examples two cases stand out: Clubul Regilor Liberi (The Club of the Free Kings) in Brăila and Organizația Tinerilor Liberi (The Organisation of Free Young People) in Bistrița.

The Club of the Free Kings was a group of fourteen- to sixteen-year-olds in Brăila who would gather and listen to RFE’s musical broadcasts, especially to Cornel Chiriac’s programme, Metronom. The Securitate opened an informative file (dosar de urmărire informativă) against the name of the initiator of the group, Puiu Apostolescu, nicknamed “Harisson,” on 27 November 1971. In fact, the investigation of the Romanian secret police had started on 4 November 1971, when its local branch in Brăila intercepted a letter sent by the group to Cornel Chiriac at RFE. Although the letter was signed by three members of The Club of the Free Kings, who used their English nicknames, it was Puiu Apostolescu, alias “O’Brien McHarisson,” who had written it and sent it to RFE through the Romanian postal system. In their message, the young people described the impact of the “Theses of July 1971,” which imposed an embargo on foreign cultural products of all kinds, and made a harsh criticism of the cultural policies of Ceaușescu’s regime and the economic difficulties that Romanians had to face in their daily life (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, file 3032 vol. 1, ff. 1–3, 21–22). The informative file against the name of Puiu Apostolescu paradoxically starts with the decision to close informative surveillance by the Securitate on 11 July 1972. Although chronological order is not strictly observed, the documents trace step by step the development of the investigation. The first documents are reports of the Brăila branch of the Securitate from November 1971 about the identification of “Harisson” as the author of a letter sent to RFE and initiator of the group called The Club of the Free Kings and also contain several pieces of information on his close friend, Marinică Odagiu. The Securitate devised a plan of measures that aimed at collecting as much information as possible about the activity of these two teenagers. This plan included recruitment of sources, interception of their correspondence, stakeout, and monitoring of their personal relations. In order to substantiate their investigation, the Securitate officials also included in the file the original letter that Apostolescu sent to RFE and the result of the graphological analysis that confirmed he was its author (ACNSAS, I 3032 vol. 1, ff. 1–22).

The Securitate collected information about Apostolescu and Odagiu using its sources. Thus, the file contains several informative notes collected in November 1971 and signed by classmates and acquaintances in which the teenagers are incriminated for listening to RFE musical programmes, for recording foreign music and sharing it with their peers, and also for creating a group called The Club of the Free Kings. More specifically, the Securitate was interested in the psychological profile of the group and the way in which listening to RFE influenced its members’ criticism of the “Theses of July 1971” and the ban on Western cultural products. As the investigation progressed, in December 1971 the Securitate started to collect the testimonies of those directly involved in the activity of The Club of the Free Kings. The testimonies, which can also be found handwritten in the informative surveillance file, present a detailed picture of the group, its members, and their activity. The development of the investigation also entailed a collaboration between different local branches of the Securitate, as some of members of the group resided in other counties than Brăila. The collaboration with the Dâmbovița county branch proved to be specifically fruitful. It not only provided new information on one member of the group, Eugen Mircea, but also brought further evidence of the cultural opposition of the group. Eugen Mircea handed over to the Securitate two badges made of wood. On one side the badges contained the name of the group, and the word “hippy”. The reverse sides of the badges contained the English nicknames of the Eugen Mircea and Puiu Apostolescu (ACNSAS, Informative Fonds, file 3032 vol. 1, ff. 23–211).

At the beginning of January 1972, the Securitate finished its investigation on The Club of the Free Kings and made a report that summarises its findings and lists the measures taken against the Club’s members. The report stated that the group was formed in July 1971 as reaction to the measures taken by the communist regime in the same month to foster the social and political education of the population. The members defined their club as hippy and imitated the hippy subculture in terms of their outfit and opposition to mainstream society and the political regime. Thus, in order to distinguish themselves from the rest of their peers, the initiator of the group, Puiu Apostolescu, created for each member badges made of wood with the name of the group and their English nicknames. Moreover, all of them agreed to wear a yellow T-shirt and an insignia with the name of the group and a flower. The main activity of cultural opposition of the members of the group was listening to the musical programmes, especially Metronom, broadcast by the Romanian department of RFE. They not only listened to foreign music broadcast by a radio station officially banned in Romania but also began to develop a critical position towards domestic policies, especially in the cultural realm. From the Securitate’s point of view, listening to RFE and especially to Cornel Chiriac’s programmes “had negatively influenced the way of thinking of those concerned as they tendentiously discussed some economic, political and cultural-educative aspects from our country, at the same time praising the capitalist lifestyle, the so-called freedom and greater chances of affirmation of the youth of those countries.” Moreover, The Free Kings expressed their discontent about the measures taken by the party leadership in July 1971 in the cultural realm, which reinforced ideological control over local cultural products and criticised subservience to Western cultural trends. The cultural opposition of this subcultural group was expressed in the letter sent to Cornel Chiriac at RFE and also during their occasional gatherings after listening to programmes broadcast by the same RFE. As for the measures taken against the members of the group, these included public debates and warnings. In January 1971, most of The Free Kings, including Puiu Apostolescu, were excluded from the communist youth organisation after their case was discussed and their behaviour incriminated in a public debate involving their colleagues and teachers. Others received warnings from the Securitate. The file also recorded the exchange of correspondence between the different branches of the Securitate that were involved in the investigation of The Club of the Free Kings. Thus, the Securitate branch in Brăila sent its final report about the group to the headquarters in Bucharest and all the county branches with which it had collaborated in this case to inform them about the conclusions and resolution of the file. The public debate and warnings of January 1972 did not end the informative surveillance of Apostolescu which continued until July 1972 (ACNSAS, I 3032 vol. 1, ff. 1–2, 29–60). Between January and July 1972, the Securitate intercepted Apostolescu’s correspondence to make sure that he had abandoned his dissident activities. The Securitate resumed its informative surveillance of the former members of The Free Kings, Puiu Apostolescu and Marinică Odagiu, in 1976 and 1981 respectively, when they were required to perform their mandatory military service. The two small informative files opened against their names consist of a general note that the Securitate sent to their military superiors to warn them about the recruits’ membership of a hippy group and a series of handwritten informative notes. The sources pointed out that these rebellious young men continued to listen to foreign radio stations and their musical programmes, to disobey authority, and to crave a bit of freedom to be themselves (ACNSAS, I 3032 vol. 2 and 3).

Among the few young people in Romania who were imprisoned because of their passion for foreign music were Emil Hidoș and Carol Pall. Members of an informal group called Organizația Tinerilor Liberi (The Organisation of Free Young People – OTL), these two young people lived in the town of Bistrița, in Bistrița-Năsăud county. In September 1970, they received prison sentences of six years and two years six months respectively, having been found guilty of “propaganda against the social order.” Their guilt related mainly to forming OTL and writing and sending letters to Cornel Chiriac, the producer of the very popular musical programme Metronom, broadcast by the Romanian department of RFE. Apart from requesting his “popp” (sic!) musical preferences, Emil Hidoș underlined in his letter to RFE the lack of liberty which young people wishing to listen to and express their attachment to foreign music and subcultures had to confront, especially the impact of Decree 153/1970, which incriminated “social parasitism” and limited even more drastically the liberties of young people. In addition to his letters to RFE, Emil Hidoș authored a samizdat in handwritten version, which he entitled due to his poor knowledge of English as Wald old popp.

The three files in the CNSAS Arhives contain relevant documents resulting from the Securitate penal investigation of Emil Hidoș and Carol Pall. In fact, the first volume of the file in divided into two main parts, corresponding to the unfolding of the penal investigation in each of the cases of the incriminated persons. The investigation started at the beginning of October 1969, when the Romanian secret police found out about a young man who used the nickname “Braim Iones” and a fictive address to send “letters containing slander and denigrating remarks about the socialist order” to RFE. The documents reconstitute the development of the investigation and identify the main actors involved in establishing Emil Hidoș as the author of the above-mentioned letters. It is interesting to remark that the Bistrița-Năsăud county branch of the Securitate wanted to be legally covered in its investigation of this case, so it started by requesting permission from the Military Prosecution Service in Cluj to intercept and confiscate the letters signed by “Braim Iones.” Having secured this permission, the Securitate asked the county postal service to intercept and send to its headquarters any letter of the sender “Braim Iones.” The investigation led to a result only few months later when the Securitate organised a search at Emil Hidoș’s home on 5 June 1970. The file contains the handwritten permission of Hidoș’s mother in which she agreed to the house being searched and also the record of what the Securitate found and confiscated as evidence. The incriminating evidence taken from Emil Hidoș’s home included ten copies of the hand-written musical samizdat Wald old popp, a chart with the names of OTL’s members, an OTL membership card in the name of Emil Hidoș, letters with “hateful content,” in original or copy, that Emil Hidoș and one of his friends had written to Cornel Chiriac at RFE, and a tape deck. In order to establish with certainty that Emil Hidoș was also the author of the letter intercepted in 1969, the Securitate asked the Cluj forensic laboratory to compare the specimen of his handwriting from this letter with that on other letters confiscated during the house search. The result that reached the Bistrița-Năsăud branch of the Securitate on 22 June 1970 confirmed that Emil Hidoș was the author of both of the analysed documents. The Securitate investigation also identified one of Hidoș’s friends, Carol Pall, who had not only signed one of the letters sent to Cornel Chiaric but had handwritten it. On 10 July 1970, the Securitate finished its report, which included an overview of the preliminary findings in the case of the two young men. Based on this report, it requested the Military Prosecution Service of Cluj to issue a warrant of preventive arrest for thirty days against the name of Emil Hidoș. Thus, the penal investigation of Emil Hidoș started on 14 July 1970 and the file contains official documents pertaining to Hidoș’s arrest, such as the warrant, his initial declaration, the choosing of a lawyer, and a record of the ID documents confiscated from the defendant (ACNSAS, P 14400 vol. 1, ff. 1–38 f–v).

The following part of the file contains seven testimonies, both handwritten and typed, signed by Emil Hidoș and taken by the Securitate officers between mid-June and the end of July 1970. The questions were aimed at identifying the circumstances in which Emil Hidoș and one of his friends wrote the letters with “hateful content” to Cornel Chiriac, how he convinced Carol Pall to sign with him a letter to RFE, who his close friends were who knew about these letters and his samizdat publication, who were members of the OTL and when and where they began to listen to Cornel Chiriac’s programme Metronom at RFE, and what “hateful” comments about the socialist order they engaged in after their collective listening to this broadcast. The file also contained the record of the confrontation between Emil Hidoș and his friend Carol Pall about the circumstances in which they wrote together the letter to RFE. On 5 August 1970, Emil Hidoș was informed about the content of his penal file and the accusations on which he would face prosecution (ACNSAS, P 14400 vol. 1, ff. 39–92 f–v). The following part of the file consists of the five testimonies of Hidoș’s co-defendant, Carol Pall, which essentially focused on the episode of their writing together the letter to RFE. This was followed by a series of testimonies of fourteen witnesses selected from those who had met and known about Hidoș’s “hostile” actions. The interrogations that lasted between mid-June and end of July 1970 focused on the circumstances in which the witness had met the defendant, when OTL was created and what its purpose was, how they had gathered to listen to the foreign “popp” (sic!) music broadcast by RFE, the comments they made at the end of the Metronom broadcast, and the contents of the letters sent to RFE and of the samizdat publication Wald old popp (ACNSAS, P 14400 vol. 1, ff. 93–180 f–v).

The next part of the file contains evidence used to build the case against Emil Hidoș. This mainly consists of copies and originals of Emil Hidoș’s letters and a copy of the samizdat publication Wald old popp. Some fragments of the documents are underlined by the Securitate officers to ease the identification of the arguments in support of the accusation of “propaganda against the socialist order.” The fragments essentially underlined the revolt of their author against the Romanian communist regime that denied him and his peers the right to spend their spare time as they wished, to listen to foreign music and to express their musical preferences through unusual outfits (ACNSAS, P 14400 vol. 1, ff. 181–244 f–v). The file also contains documents pertaining to the penal investigation of Carol Pall. It consists of the same types of documents collected in the case of Emil Hidoș, such as those relating to granting and receiving permission to intercept his correspondence sent under the nickname of “Furmanek Alexandru,” the organisation and result of his house search, the forensic analysis of his hand writing, the issuance of a warrant of preventive arrest for thirty days, and Carol Pall’s initial declaration and appointment of a lawyer. The file also contains five testimonies of the defendant, Carol Pall, three testimonies of Emil Hidoș and a record of the confrontation of their declarations. These documents were collected between June and July 1970 and some are identical to those used in the course of Hidoș’s penal investigation. They dealt especially with the episode of the writing and sending of a letter to Cornel Chiriac at REF. The Securitate also collected three testimonies from witnesses that testify to the interest shown by Carol Pall in foreign music broadcast by RFE and attached to the file a series of items of evidence, including the letter handwritten by him for sending to RFE and a list of foreign songs and bands. On 6 August 1970, Carol Pall was informed about the content of his penal file and the charges brought against him. On 15 august 1970, the Military Prosecutor in Cluj agreed to put Emil Hidoș and Carol Pall on trial and sent the file to the Military Tribunal in Cluj. The file preserves the traces of the organisation of the trial which included the citations of the defendants and witnesses, the appointment of defence attorneys, the declarations of the defendants and witnesses during the trial on 8 September 1970 and the pronouncement of the sentence on 9 September 1970. Both defendants appealed against the sentences received and the trial was transferred to the Military Tribunal in Bucharest which confirmed the initial verdicts. Accordingly, the file contains the appeal requests of the two defendants, their motivations of appeal, the final decision of the Military Tribunal in Bucharest, and other documents needed for their detention at the Vacărești Penitentiary in November 1970 (ACNSAS, P 14400 vol. 1, ff. 245–417 f–v).

The second volume of the file reconstructs the fate of Emil Hidoș and Carol Pall during their time in prison. In 1972 and 1973, Carol Pall and Emil Hidoș were pardoned and released without serving the rest of their sentences. Thus, the file contains the correspondence between the Aiud Penitentiary, the General Directorate of Penitentiaries, the lawcourt of Alba county (where Aiud is situated), and the Bistrița-Năsăud branch of the Securitate about the release of the two defendants. Again the documents in the file are separated into two parts, one for each of the convicted. The first concerns Carol Pall and includes the rejection of his appeal made to the State Council, the documents about his imprisonment at Văcărești Penitentiary and his transfer in December 1970 to Aiud Penitentiary, and several positive evaluations of his behaviour during imprisonment. The other documents go back to the judicial events that led to his prison sentence. With few exceptions, the materials concerning Emil Hidoș are identical with those in the first volume, and capture the development of the penal investigation from his preventive arrest and his and witnesses’ questioning to the pronouncement of the sentence, imprisonment in Văcărești Penitenciary after the rejection of his appeal, and the subsequent transfer to Aiud Penitenciary in December 1970. Additionally, the file contains evaluations of Hidoș’s behaviour during the prison sentence and administrative decisions for his confinement in isolation due to his recalcitrant behaviour and disobedience towards prison authorities and rules (ACNSAS, P 14400 vol. 2). The third volume of the file contains only copies of the documents regarding the penal investigation of Emil Hidoș and Carol Pall that can also be found in the first two volumes (ACNSAS, P 14400 vol. 3).

Description of content

-

The documents in the Youth Subcultures Ad-hoc Collection at CNSAS were organised by the Romanian secret police, the Securitate, depending on its operative interests and bureaucratic rules, into three categories of files: files from the documentary fonds about “problem youth–education” and “problem art–culture,” files regarding the surveillance of groups of persons who expressed their passion for foreign music and Western musical subcultures (the so-called informative surveillance files (dosare de urmărire informativă), and files from the criminal fonds about the Securitate’s investigation that led to the imprisonment of some young Romanian fans of alternative subcultures. The files from the documentary fonds contain reports of the county branches of the Securitate concerning the emergence of Western-inspired youth subcultures, such as hippy, punk, new wave, or rock, and the csöves subculture, which Hungarians in Romania adopted under the influence of punk subculture in Hungary. Consequently, the Securitate increasingly started to focus on identifying the sources from which young people could find out about foreign music. The documents show how young people, alone or in small groups, listened to foreign radio stations, tried to get in contact with the producers of Western radio programmes to request the broadcasting of their favourite songs, and made recordings of foreign music on magnetic tapes or on cassettes and shared them with their peers. The Securitate reports also document the travels of those young people who were allowed to cross the border, but then smuggled back into Romania vinyl discs, cassettes, and musical magazines, which could not be bought in local shops. Under the influence of these foreign cultural products, they started to express after their return their allegiance to Western youth subcultures by changing their public outfit and behaviour. The Securitate reports paid a great attention to how the consumption of Western music changed the way in which young people behaved and dressed. As a result, the secret police officers noted, young people chose English names for themselves and their alternative groups, began to comment negatively on living conditions in Romania, stressed their lack of freedom in comparison to their Western peers, and used bricolage and artefacts to imitate the alternative life styles using whatever was available to them. The Securitate reports also paid a great deal of attention to “youth entourages,” or informal gatherings that young people created for hanging out and listening to foreign music, usually broadcast by RFE. Thus, the county branches began to gather information about the names of the groups, and personal information about their founders, about the members of the “entourages,” their behaviour, and their outfits, while underlining what kind of measures (warning, public debate, and “positive influencing” measures) were taken in order to dismantle the groups and made sure that their members abandoned their alternative behaviour.

Among the cases in which the Securitate opened a file of informative surveillance against the name of the members of a hippy, punk, or rock fan group was Clubul Regilor Liberi (The Club of the Free Kings) in Brăila. The club was, in fact, a group of fourteen- to sixteen-year-olds in Brăila who liked to hang out and listen to RFE’s musical broadcasts, especially to Cornel Chiriac’s programme Metronom during their spare time. The Securitate opened an informative surveillance file against the name of Puiu Apostolescu, nicknamed “Harisson,” on 27 November 1971. Puiu Apostolescu was the creator of the group and the author of a letter to Cornel Chiriac which was intercepted by the Securitate. The letter contained a harsh criticism of the “Theses of July 1971.” The documents in the informative surveillance file consist of several types. There are reports of the Brăila and Dâmbovița branches of the Securitate about Harisson and his friends, the findings of their surveillance activity, the impact of the measures taken to dismantle the group, and plans for measures of informative surveillance aimed at collecting as much information as possible about Puiu Apostolescu and other members of the group. Equally important are the informative notes and testimonies of those directly involved in the activity of the club, which present a detailed image of the group, its members and activity. A distinct category of documents is represented by the evidence collected by the Securitate in its efforts to assess the nature and the purposes of the club. These included the letter (in original) that Apostolescu sent to RFE and photographs of two badges made of wood that were the distinctive sign of the members of The Club of the Free Kings.

A second interesting case of persecution against young people who embraced alternative subcultures is that of Organizația Tinerilor Liberi (The Organisation of Free Youth – OTL). Two members of this group, Emil Hidoș and Carol Pall, stand out among the cases of Romanian young people who were punished by the communist regime because of their passion for foreign music. In September 1970, they received sentences of six years and two years six months respectively having been found guilty of “propaganda against the social order.” In fact, their guilt was related to their membership of OTL and their writing and sending letters to Cornel Chiriac at RFE. Apart from requesting their “popp” (sic!) musical preferences, the two young people deplored the lack of freedom for young people who wanted to listen and to express their attachment to foreign music and subcultures, and the limitations imposed by Decree 153/1970 on “social parasitism.” Moreover, Emil Hidoș authored a samizdat handwritten publication that due to his poor knowledge of English had the misspelled title Wald old popp. The three files in the CNSAS Arhives contain relevant documents resulting from the penal investigation of Emil Hidoș and Carol Pall mounted by the Romanian secret police. They were created between October 1969 and 1972 and 1973 respectively, when Carol Pall and Emil Hidoș were released from prison. These documents deal with the development of the investigation and identify the main actors involved in establishing Emil Hidoș and Carol Pall as authors of the letters sent to RFE. The materials include official correspondence between the local Bistrița-Năsăud branch of the Securitate and the Military Prosecutor and Tribunal in Cluj and between the General Directorate of Penitentiaries and the Văcărești and Aiud Penitentiaries regarding the collection of evidence against the two defendants, the conclusions of the investigations, the sentences, their appeal, their imprisonment, and finally, their release before the completion of their sentences. Another category of documents includes the papers concerning the unfolding of the penal investigation, such as the testimonies of the defendants and of witnesses, a record of the confrontation between the testimonies of Emil Hidoș and CarolPall, and the lists of evidence used to build the case against the two. A special category of documents consists of the evidence gathered by the Securitate. This includes the letters written and sent by Emil Hidoș to Cornel Chiriac at RFE, the letter written together with Carol Pall, the internal documents of the OTL (list of members, membership card), lists of the two defendants’ favourite artists, bands, and songs, and ten copies of the samizdat publication Wald old popp (sic!).

Content

- grey literature (regular archival documents such as brochures, bulletins, leaflets, reports, intelligence files, records, working papers, meeting minutes): 1000-

- manuscripts (ego-documents, diaries, notes, letters, drafts, etc.): 10-99

- photos: 10-99

- publications (books, newspapers, articles, press clippings): 0-9

Owner(s)

Stakeholder(s) of the collection

Geographical scope of recent operation

- international

Topics

Place of founding

-

Bucharest, Romania

Show on map

Creator(s) of content

Collector(s)

Important events in the history of the collection

Featured items

Access type

- completely open to the public

Author(s) of this page

- Marin, Manuela

References

ACNSAS, Fond Documentar (Documentary fonds), files: D 8833 vol. 10, 11, 14, 15, 18, 25, 36, 41, 43, 45, 47, 50, D 8687, D 12550 vol. 1, D 13365 vol. 1, D 18306 vol. 7, 11.

ACNSAS, Fond Informativ (Informative fonds), files: I 3032 vol. 1–3, I 855732 vol. 1, I 906390;

ACNSAS, Fond Penal (Penal Fonds), files: P 14400, vol. 1–3

Burlacu, Liviu. 2009. “Preventive Measures Used by the Securitate.” In Learning History through Past Experiences: Ordinary Citizens under the Surveillance of Securitate during the 1970–1980s. Edited by Virgiliu Țârău, 64–66. Bucharest: Editura CNSAS, 2009.

Ryback, Timothy W. 1990. Rock around the Bloc: A History of Rock Music in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Țârău, Virgiliu, interview by Marin, Manuela, July 15, 2018. COURAGE Registry Oral History Collection

How to cite this page?

COURAGE Registry, s.v. "Youth Subcultures Ad-hoc Collection at CNSAS", by Manuela Marin, 2018. Accessed: January 26, 2026, doi: 10.24389/125104