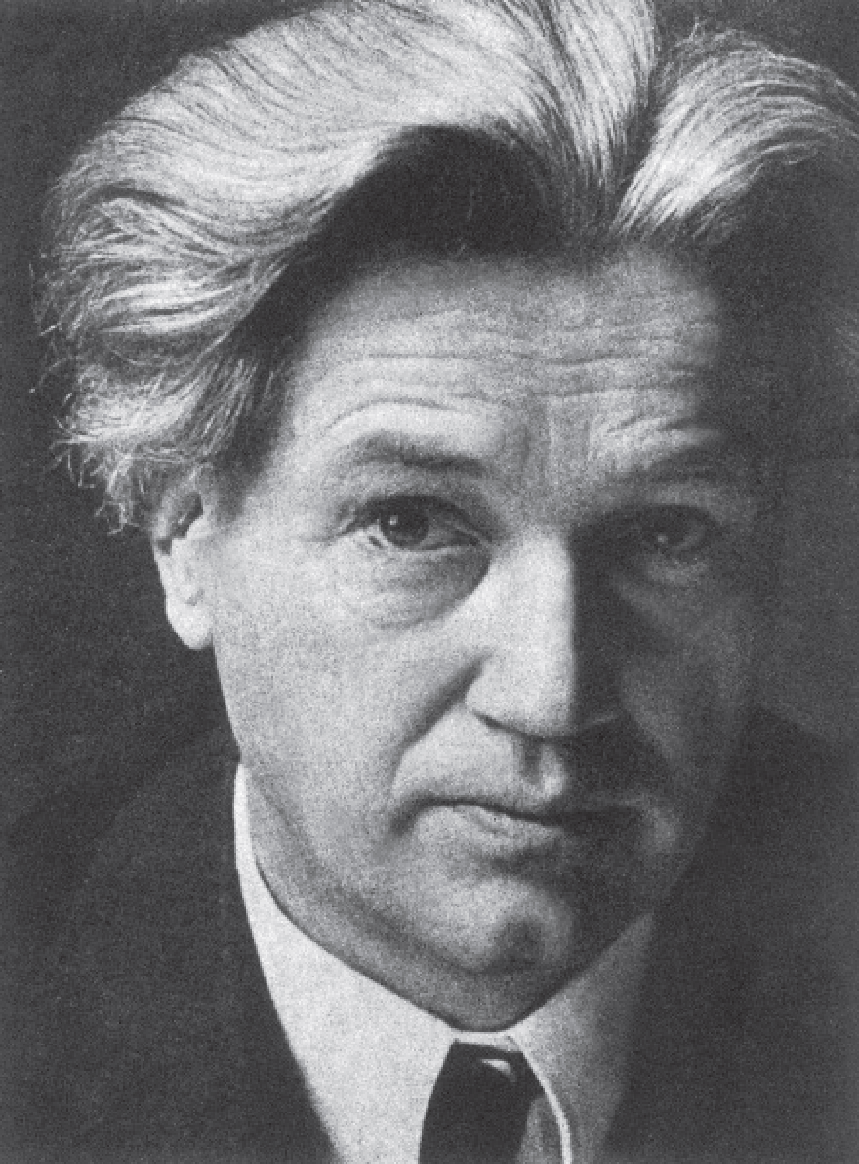

Ivan Supek was a Croatian physicist and writer and one of the most prominent Croatian engaged intellectuals in the latter half of the 20th century. He was born in Zagreb in 1915, where he graduated with degrees in mathematics and physics from the Faculty of Humanities and Social Science in 1939. At the end of 1940, he obtained his doctorate in physics in Leipzig, after which he became an assistant to Werner Heisenberg and worked on research into superconductivity and quantum electrodynamics. As a young man in the early 1930s, he joined the League of Communist Youth of Yugoslavia (SKOJ), and then the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ). However, at the end of the same decade, during the so-called “conflict on the left,” he refused to “inherit the dogmatically understood dialectical materialism which he considered incompatible with modern knowledge, freedom and creativity,” and when he refused to accept Stalin's infallibility, “he was excluded from the KPJ in 1940” (Kutleša & Hameršak 2015).

In March 1941, because of his anti-fascist attitudes and activities, he was arrested by the Gestapo, but after several months he was released at Heisenberg's intervention. Instead of continuing his work with Heisenberg, Supek returned to Zagreb and joined the anti-fascist movement in Croatia. As a member of the Presidency of the First Congress of Croatian cultural workers in Topusko in June 1944, he held the only speech on science, emphasising the potential danger of developing nuclear weapons (http://info.hazu.hr/en/clanovi_akademije/osobne_stranice/ivan_supek).

After the Second World War, he was the first professor of theoretical physics at the Faculty of Science and Mathematics (University of Zagreb), where he founded the school of theoretical physics. He was also the founder and the first director of the Ruđer Bošković Institute (IRB), founded in 1950 for research in the field of atomic physics. Supek was “the most prominent opponent of the political drive in Yugoslavia aimed at the development of nuclear weapons” (Ilakovac 2013, 37). That is why he was forced to resign from the IRB in 1958 (Ilakovac 2013, 16).

Besides his work in the field of physics, he made a significant contribution to the philosophy of science, striving to link the natural sciences with philosophy, art, humanism, religion and ethics. He was the first professor of philosophy of science at the University of Zagreb. In the Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts (JAZU, today the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, HAZU), of which he was a full member since 1961 (he became a corresponding member in 1948), he founded the Institute for the Philosophy of Science and Peace in 1965. The foundation of this institute was a part of his efforts in the struggle for the principles of peace, prosperity and disarmament, which was then most actively promoted at the global level by the Pugwash Movement. He joined the movement in 1961 and initiated the formation of its Yugoslav branch. On this agenda, Supek developed intense international cooperation and initiated and edited the journal Encyclopaedia moderna, which was also based on the principles of the Pugwash Movement.

During the Croatian Spring, he was the chancellor of the University of Zagreb (1968-1972) and encouraged the establishment of the Inter-University Centre in Dubrovnik (1970). Because of his disapproval of the conclusions of the twenty-first session of the Presidency of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia in December 1971, which condemned the goals of Croatian Spring, and because he expressed solidarity with the persecuted Croatian intellectuals after the fall of the Croatian Spring, he came under attack by the regime and in the 1970s he was marginalized as politically unfit. Then he turned to the literary work that had preoccupied him since his youth.

He wrote mostly novels and plays. In 1959, he wrote his first novel Dvoje između ratnih linija (Two Between the Firing Lines), inspired by the so-called “conflict on the left” before the Second World War and concerned with the fate of an individual caught between conflicting collectives. In the same year, he published the play Na atomskom otoku (On the Atomic Island), which was soon banned, because the censors realised that it was a critique of the secret nuclear bomb project in Yugoslavia (http://info.hazu.hr/hr/clanovi_akademije/osobne_stranice/ivan_supek).

In the 1960s, he wrote several historical novels and dramas, some of which may be seen as expressions of disagreement with the social and political system in Yugoslavia. The biographical-historical drama Heretik (The Heretic, 1968) was the only of his plays that was well received by audiences and critics. While telling the story of the Renaissance heretic Mark Antun de Dominis, Supek alluded to the status of dissidents in the latter half of the 20th century. In this drama, he also alluded to his own position as a man acting against the dominant social streams (Senker 2015, 45), although at that time (in the 1960s) he still had a distinguished position in public life (interview with Marotti, Bojan). After the fall of the Croatian Spring, his works became undesirable to the authorities. The first edition of his novel Opstati usprkos (Surviving in Spite, 1971), was burned at the beginning of government’s clash with the Croatian Spring, and his novel Extraordinarius was withdrawn from sale in 1974 because of content that alluded to the Croatian Spring, (Kutleša & Hameršak 2015).

In the 1980s he fell into even greater disfavour due to his writing. The book Krivovjernik na ljevici (Heretic on the Left) had a significant impact. The book was published in Bristol in 1980. It depicted the most recent history of Croatia from Suepk’s perspective and criticised the repressive methods by which the Communist Party built its totalitarian rule in Yugoslavia. That is was why he found himself in the line of fire by dogmatic communists. These attacks intensified after 1983, when a portion of Supek’s memoirs was published in the book So Speak Croatian Dissidents (Norval: Ziral), and especially when he published his book Krunski svjedok protiv Hebranga (Crown Witness against Hebrang) in Chicago (in English and Croatian). Supek described the circumstances of Andrija Hebrang's murder and the role of the UDBA (State Security Service) in that act. The regime unjustifiably began to label Supek as an “Ustasha” and a “leader of hostile émigré communities.” He was called for interrogations by the police, and his passport was confiscated, which was particularly difficult for him as an internationally renowned scientist.

As the crisis of the communist system in Yugoslavia escalated, Supek renewed his public activity and welcomed the introduction of the multiparty system (Ilakovac 2013, 21). In 1991 he was elected president of the JAZU (which was soon renamed HAZU) and remained at its head until 1997. He was a vocal opponent of the military aggression against the Republic of Croatia in the early 1990s and sought support from the global public for Croatia's struggle for independence. He was also a harsh critic of all democratically elected Croatian governments, stressing certain negative social phenomena (Ilakovac 2013, 40-41).

According to some of his associates, Supek liked to act outside of institutions. Though he was a left-wing intellectual, the militant aspect of socialist regimes deterred him from fostering closer co-operation with communist rulers (interview with Marotti, Bojan). Bojan Marotti describes him in an interview for COURAGE as an individual who liked his heretical position, as a man who always walked in the opposite direction, who opposed the state and the prevailing currents in everything. Even after the collapse of communism, when Croatian patriotism became the dominant paradigm, he soon moved to a specific heretical position, although he was a Croatian patriot (interview with Bojan Marotti). Supek received the Ruđer Bošković Award for Science (1960) and the Republic of Croatia Lifetime Achievement Award (1970), and the Croatian Post Office issued a stamp bearing his image in 2015 (Kutleša & Hameršak 2015). He died in Zagreb in 2007. He was the brother of sociologist and philosopher Rudi Supek.