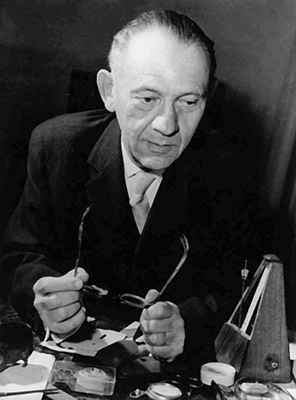

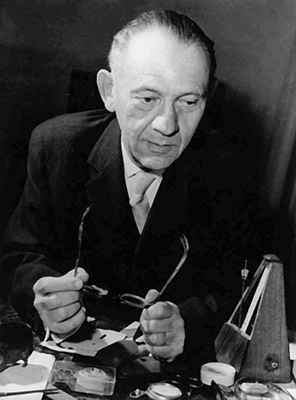

László Lajtha was born in Budapest (Hungary), on 30 June 1892. He was a composer, ethnomusicologist, and conductor.

His parents were Ida Wiesel and Pál Lajtha.

As a child, he was quite impressed by Transylvanian folk music. He also liked French music, and his favorite composer was Claude Debussy.

Lajtha studied composition, piano, and music at the Academy of Music in Budapest, where he earned his degree in 1913. He also studied in Leipzig, Geneva, and Paris, where he was a pupil of the famous French composer, Vincent d’Indy. Lajtha began collecting folk music and folk songs in 1910, and he joined the great movement launched by Béla Bartók. In 1913, he started work as a civil servant at the Museum of Ethnography in Budapest. That same year, his first work, D’un cahier d’esquisses (From a Musician’s Sketchbook), appeared in print. News of this work spread rapidly, and Lajtha became famous as an avantgarde musician. Two other piano pieces, The Sonata and Tales, were published in 1914 and 1915. Lajtha’s musical career was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I, which also forced him to break with his French connections. In 1919, he became a professor of composition and chamber music at the National Conservatory of Music in Budapest. In 1928, he became an active member of the International Commission for Popular Arts and Traditions, and two years later he was elected as the president of the Music Department of the commission. Between 1928 and 1939, he became well known throughout Europe, where his chamber music and symphonic works were played. His ties with France were strong, and he made several friends among prominent French composers (Ravel, Roussel, Ibert, Rivier, and Barraud). During this successful period, he became an honored member of the École de Paris, but the outbreak of World War II broke these ties (despite his efforts to keep in touch with his friends and, when possible, to leave Hungary for Paris). In 1947–48, he spent a year in London working with T. S. Eliot on the score for the film Murder in the Cathedral, an adaptation of one of Eliot’s works. Lajtha returned to Hungary in 1948, and he became involved in the resistance against the new political regime. Although he was a world-famous composer, Lajtha was denied a passport at home and was thereby forced to remain in Hungary. The new political regime felt threatened by his fame, and it hindered his career to the point that he was only allowed to collect folk music and songs. He received the most prestigious state award, the Kossuth Prize, in 1951. He donated the prize money to the poor. In the 1950s, following the ban on religious practice, he wrote symphonies (e.g. Op. 63-as VII.) and masses, and he composed his Magnificat in 1954 and wrote Marian anthems in 1958. He began collaborating with Margit Tóth and Zsuzsanna Erdélyi in 1953. Together, they collected folk songs, folk music, and archaic prayers in Transdanubia (the western part of Hungary). They referred to themselves as “Noah’s Ark.” In 1955, Lajtha, as the only Hungarian composer, was elected as a corresponding member of the Institut de France (Académie des Beaux-Arts). In 1962, he was finally allowed to travel to France.

László Lajtha was married to Róza Hollós. They had two sons.

Lajtha died in Budapest on 16 February 1963.