Atanas Vasilev Patsev was a Bulgarian painter and illustrator. As a secondary-school boy, Patsev joined the communist revolutionary movement and became a partisan.

In 1949, he graduated from the State Academy of Arts, in the class of Prof. Dechko Uzunov.

During the 1960s, his method of work changed in favour of the modern means of the expressive sculpture and painting. In 1968, his exhibition "Weightlessness" provoked confusion among the authorities responsible for the ideological correctness of art. The exhibition was accompanied by a small brochure containing text by the author as well defining weightlessness as a leading principle of the composition. "The form has no weight. It becomes unstable, transparent. The familiar silhouette loses shape. As if the inner construction of the body becomes visible. As if the range of visibility expands. The motion becomes six-way, rotary, supple and undulating" (Patsev, quoted after Iliev 2016: 153). The exhibition took place in a time when the situation in Paris was revolutionary and the Prague Spring was at its height.

Patsev's call for plastic revolution was initially wrapped in silence but afterwards defeating reviews were published: "roughly deformed bodies and practices", "a mixture of styles". The exhibition was attacked for "not containing any new problems" and the author was accused of "discrepancy between theory and practice" (Iliev 2016: 153). The philosophy of weightlessness was perceived as a threat to the regime whose ideology was based on the theorem of control of the Party-state over all processes. "The deprivation of gravity of the person represented is determined as theoretical vandalism similar to anarchism because the concept of the place of the particular individual puts him in a strict rank, together, united, in the group, in the team, at the meeting, at a manifestation. The idea of the different points of view is opposite to the only true uniform line represented by the Party" (Iliev 2016: 153).

Paradoxically, Patsev was simultaneously accused of secession, cubism and expressionism – styles defined by the party ideologists as "noxious", "decadent", "effete" bourgeois forms of plastic thinking.

In the next years, Atanas Patsev created big cycles of paintings on subjects related to the anti-fascist resistance ("Partisan Recollections"). The themes were ideologically orthodox – the events were promoted to mythologized heroism. However, the plastic language did not correspond to the pattern. The paintings of the cycle "The Man and the Things" were perceived as an attack of Patsev on the communist ruling crust tempted by gaining.

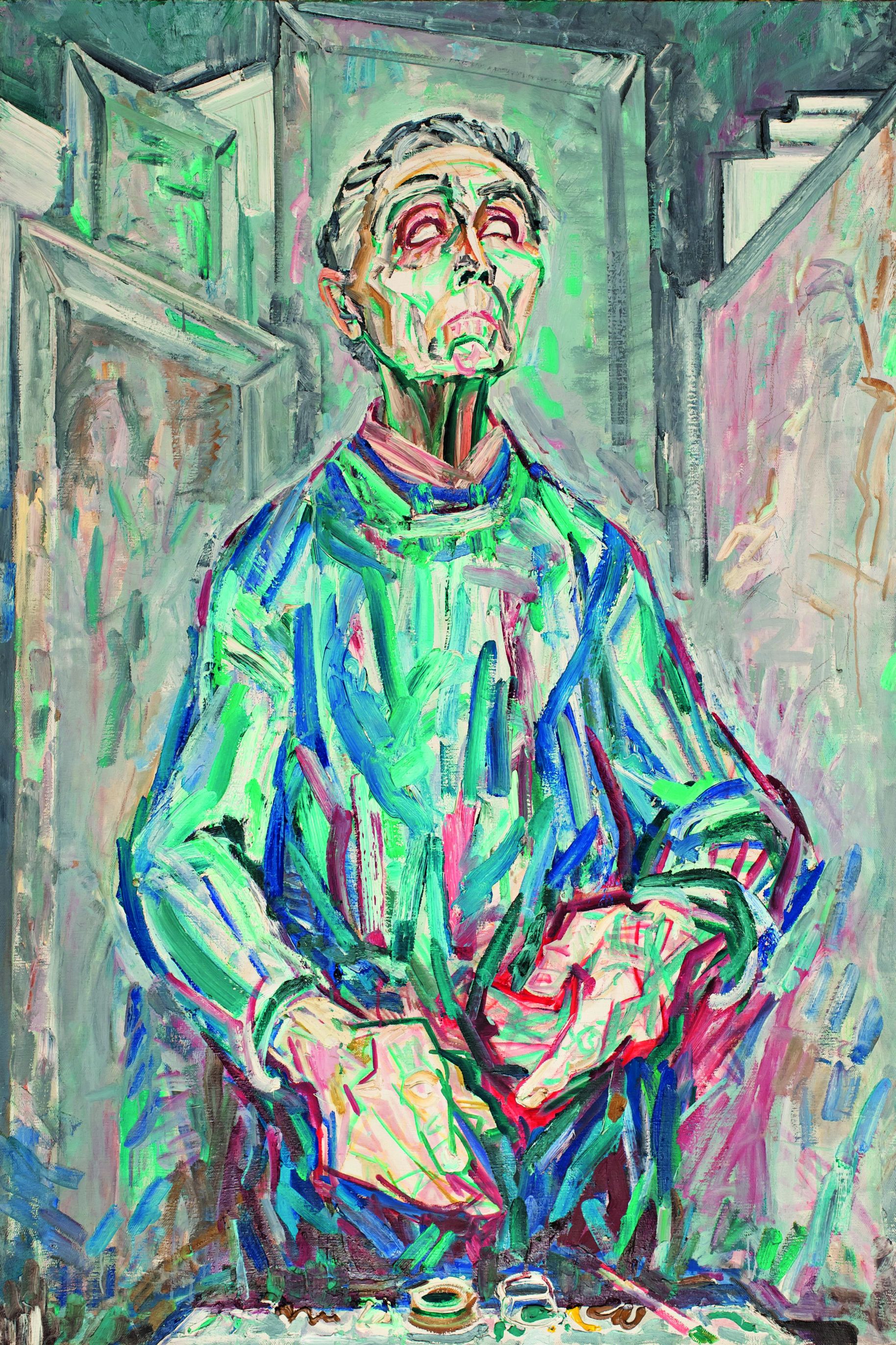

The portraits painted by Atanas Patsev combine "analytical mind and emotional expression" (Iliev 2016: 156). The portrait of Kiril Petrov (1976, Kiril Petrov – a painter who spent many years in estrangement and self-isolation from the public art life after being accused of "formalism") is created with dynamic contrasting colours so that the view of the head is from below and that of the arms is from above. Using the means of perspective, Patsev upsets the balance of the viewer's static contemplation. "Kiril Petrov forecasts through the hatches of Patsev [...] The resistance of Atanas Patsev against the System is the resistance of a man religiously believing in its ideological righteousness, on the one hand, but on the other hand, of a painter who sees its visible ugliness. The painter fights against its main principle – the submission to the rules, standards and instructions. And sometimes, flying on the wings of the subconscious sense of the divine, he manages to escape the locked room of the ideologized mind" (Iliev 2016: 156-157).

There is no monograph published.