The Doina Cornea Ad-hoc Collection at CNSAS includes all the documents confiscated by the Securitate from Doina Cornea and the persons who supported her oppositional activities, as well as documents created by the Securitate in the course of its activity of keeping under surveillance and repressing this prominent Romanian dissident. The files created by the Securitate on Cornea’s case reflect on the one hand the complexity and uniqueness of her dissident activities in communist Romania, and on the other the prodigious efforts of the secret police to keep her under surveillance, intimidate, isolate, and repress her. The collection illustrates that oppositional activities in Ceauşescu’s Romania were “a transnational enterprise” for several reasons (Petrescu 2013, 383). More than in other countries of the Soviet bloc, in Romania the broadcasts of Western radio stations played a key role in keeping people informed about the activity of the very few, who openly opposed the regime. The effectiveness of the repressive apparatus in cutting the channels of communication between Romanian citizens and preventing collective displays of solidarity against the regime partially explains this special role. In this respect, the Doina Cornea Ad-hoc Collection depicts through the eyes of the secret police how Cornea (with the help of her relatives and friends in the West) managed to create a network of communication with Radio Free Europe (RFE) and members of the Romanian exile community through which her critical voice reached the ears of Romanian citizens.

The Securitate’s tremendous endeavours to prevent her oppositional activity from 1982 to 1989, which contrast with her fragile appearance, epitomise the asymmetric conflict between state and dissidents in communist Eastern Europe. The complexity of the Securitate’s operations concerning her case is mirrored by the quantity of files produced by the secret police dealing with Cornea’s oppositional activities (forty-five volumes of documents). Her files also exemplify the most important surveillance techniques and strategies of intimidation used by the Securitate during the 1980s in order to prevent or stop oppositional activities. The files could be divided into two parts, taking into account the inner logic of their creation by the Securitate. The first part, comprising the greater part of the volumes (forty-one out of the total amount) is made up of the so-called “informative surveillance file” (dosare de urmărire informativă) against her name. As its name shows, this kind of file is mainly the result of the gathering of information by the secret police through surveillance activities. The second part is made up of the “criminal file,” which is the result of the criminal investigation conducted by the Securitate on Doina Cornea and her son Leontin Horaţiu Iuhas in 1987 after their arrest for political offences. Although both sharing the general inner rules of the Securitate’s bureaucracy, these two files are different due to the distinct aims of the activity behind them: 1. in the first case, surveillance activities performed in order to prevent oppositional initiatives against the regime; 2. in the second case, repression of the oppositional initiatives.

The “informative surveillance file” was not only aimed at providing the repressive apparatus of Ceaușescu’s regime with information about Cornea, but also at influencing her to stop her dissident activities. This file is made up of: 1. documents produced against her name by the Securitate’s officers and “collaborators”; 2. documents created by Doina Cornea, her relatives, friends, and acquaintances which were intercepted by the secret police (e.g., via interception of letters). The informative notes and the transcripts of her phone conversations intercepted by the secret police make up a significant part of the files. These documents give us a detailed insight into the process of drafting and sending to the West the documents by which Doina Cornea opposed the policies of Ceauşescu’s regime in the fields of education, culture, religion, the economy, and urban and rural planning. They help us to grasp the intellectual atmosphere of the 1980s and the difficulties of everyday life in a country heavily affected by shortages of almost all basic products. Another part of the files is made up of administrative documents that reflect the inner functioning of the Securitate’s bureaucracy. This part is also a source for documentation on the strategies and techniques used by the Securitate in order to keep under surveillance, contain, intimidate, and repress Romanian dissidents.

As Katherine Verdery observed while studying her personal file created by the Securitate, the secret police paid special attention to the social milieu of the people under surveillance (Verdery 2014, 187). In fact, the Securitate perceived, planned, and conducted policies on individuals taking into account their social network. In Cornea’s case, the Securitate aimed on the one hand to identify her contacts, to penetrate her milieu with informers in order to get more information about her thoughts and actions, and on the other hand to influence and isolate her in order to stop her oppositional activities. Her surveillance file is a perfect example of how the Securitate “colonized social relationships” and tried to manipulate them in order to reach its aims (Verdery 2014, 26).

This special attention paid to social networks is also reflected by the schemes drafted by the Securitate with all the persons with whom Doina Cornea entered into contact (ACNSAS, vol. 10A, ff. 403–409). The secret police kept a strict record of these contacts, trying to get information about their nature, but also putting much effort into attracting persons among them to become informers. Consequently, the secret police attracted members of her close social milieu to collaborate, and even managed to infiltrate informers within the network used by Cornea to send her letters to the Western press. Although initially successful in preventing a few letters from reaching their addressees, the secret police did not manage either to block her communication with the West, especially with RFE (and thus with its Romanian listeners), or to influence her to cease her oppositional activities (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol. 2, ff. 69–70).

The surveillance file created by the Securitate on Doina Cornea has its roots in 1949, when the Romanian dissident (at that time a student at Victor Babeş University of Cluj, later Babeş-Bolyai University) was interrogated by the Securitate. Cornea was picked up by the secret police, who found in her possession a circular letter drafted by the Greek-Catholic bishop Ioan Suciu (the first Greek-Catholic bishop arrested by the communist authorities in 1948). After giving a statement at the Securitate in January 1949, Doina Cornea was released (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol. 1, f. 4). In her post-1989 interviews, Doina Cornea confessed that she had intended to pass that circular letter to other persons, but had not managed to do so. The circular letter, her statement, and other documents summarising her personal information were kept in her personal file. Although, the file created on this occasion did not contain any significant oppositional activity, the Securitate’s department in charge of archiving the files of the secret police decided in July 1963 to keep her file by invoking its pertaining to the field of “religious activity” (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol. 1, f. 2).

From 1949 to 1979, the Securitate did not manifest any interest in her, and consequently no document can be found in her surveillance file from this period. In the meantime, Doina Cornea graduated in Philology from the University of Cluj and in 1958 she became a lecturer in French literature at the same institution. In the 1970s, Cornea started to listen frequently to the radio programmes broadcast by RFE, through which she managed to be informed about the activity of Paul Goma and (later) of other Romanian dissidents (Cornea, 2006). In 1977, she took the initiative to translate literary texts by Goma with her students during her classes at the University of Cluj. This was considered by Cornea to be a gesture of solidarity with Goma’s dissident activity (Cornea 2009, 161–165).

In 1976, her daughter Ariadna Iuhas chose not to return to Romania after visiting France with a scholarship. Afterwards, Doina Cornea received from her daughter by post or through friends and relatives publications from Western Europe, including many books that were forbidden in Romania. The books sent by her daughter, especially those by the Romanian philosopher and historian of religions Mircea Eliade, who had remained in the West at the end of the Second World War, exercised a deep influence on her. During the late 1970s, Doina Cornea started to mention works by Eliade, which were not authorised by the censorship, during her teaching at the university. One of these works was the book L’épreuve du labyrinthe: Entretiens avec Claude-Henri Rocquet (Eliade and Rocquet, 1978), in fact a volume comprising interviews conducted by Claude-Henri Rocquet with Eliade. This book gave Cornea’s students an insight into interwar Romania, but also into the international academic career of a Romanian intellectual living in exile. Later, she translated this book into Romanian and circulated it as a samizdat publication in more than 100 copies. The copies were made with the help of her son Leontin Horaţiu Iuhas and of other friends, who supported her financially and logistically (Cornea 2009, 188–190). As she confessed in the interviews, she distributed these copies and other materials as if she was living in a free country and assumed that among those receiving them might be informers or Securitate employees: “I was thinking that even giving them [books and copies of them] to a possible informer or a Securitate employee was not meaningless. I was telling myself ‘he learns something by reading a book’” (Cornea 2009, 190–191; Cornea 2006, 40). On the occasion of their searches of her home in November 1987, the Securitate confiscated a copy of this translation, which was archived in the criminal file (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 1, ff. 54–58). Another copy of this samizdat is now preserved in the Museum of the Sighet Memorial.

During some classes taught in 1979 she conveyed to the students her thoughts about Eliade’s works and stated that he would not have been able to create them in communist Romania due to the lack of intellectual freedom (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol.2, f. 51–52). She also encouraged the students to express their thoughts freely despite the censorship and the pressures of the state authorities. The books published in the West that Cornea circulated, together with her non-conformist classes, stirred a strong interest among her students (Cornea 2009, 167–168). Due to these non-conformist classes which took place in the period from 1979 to 1981, Doina Cornea became a main target of Securitate surveillance activity at the Faculty of Letters of the University of Cluj. The secret police assessed her activity in this period as “dangerous” for state security (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol. 2, ff. 1–8). After receiving a detailed report on her activity on March 1981, a head of department of the Cluj county branch of the Securitate asked for “urgent measures” because “such an attitude towards the students could not be tolerated [by the state authorities]” (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol. 2, f. 28).Consequently the Securitate opened an “informative surveillance file” (dosar de urmărire informativă) on Doina Cornea’s case on 25 October 1981 and gave her the code name “Diana” (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol. 2, ff. 1-8). The “informative surveillance file” was a more complex and intense form of surveillance, which involved the most important techniques used by the secret police: close monitoring of her everyday life and social contacts through the activity of informers and Securitate employees, intercepting telephone conversations and correspondence, placing microphones in private homes (CNSAS 2018). Following the instructions of the secret police, Doina Cornea was “unmasked” at a meeting of the staff of the Faculty of Letters in February 1982, during which she was criticised by the rector of the university and summoned to give up her critical attitudes towards the regime (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol. 2, f. 12).

Another turning moment in the evolution of the surveillance file was in August 1982, when a letter by Doina Cornea was read during a radio programme broadcast by Radio Free Europe. The letter was sent to the West through her daughter, Ariadna Combes (née Iuhas), who visited her family a month before the broadcast (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol. 2, f. 11). The letter identified the causes of the general crisis that affected Romania during the 1980s in the decay of moral and cultural values, and conveyed a vocal critical stance towards the conformism of Romanian intellectuals and asked for a reform in the educational system. Doina Cornea did not want her name to be mentioned by RFE, but her identity was revealed by mistake by the editors of the RFE programme (Cornea 2006). The broadcasting of her letter by RFE had a strong impact on the Securitate’s policies on her case, leading to an intensification of their surveillance activity. This effect is perceivable in the evolution of the surveillance file. More than ninety-five percent of the documents issued by the Securitate on her case were produced in the period from August 1982 to December 1989. Due to the pressures from the secret police, the university fired her in June 1983 (Cornea 2009, 176–177).

Despite the fact that she and her family became the target of various harassments and threats from the state authorities, Cornea continued to send open letters of protest to RFE. From 1983 to 1987, she criticised in her open letters the official cultural policies and the educational system in Ceaușescu’s Romania, the obedience and conformism of Romanian intellectuals when faced with these policies, and generally the habit of the majority of Romanian citizens of accepting the lies promoted by official propaganda. She managed to send these letters by using not only the network of relatives and friends living in the West, but also foreign journalists and tourists visiting Romania. In a few cases the Securitate intercepted these letters (ACNSAS, FI 000 666, vol. 2, ff. 69–70). However, as her son Leontin Horaţiu Iuhas reveals, Cornea would send multiple copies of the same letter using different channels in the hope that at least one copy would reach its destination (Interview with Leontin Horaţiu Iuhas). Due to the Securitate’s special interest in her Western contacts, a significant part of the documents from the Cornea’s surveillance file are reports on the monitoring of these contacts, transcriptions of tape-recorded phone conversations, copies of her foreign correspondence, and reports about RFE broadcasts regarding Cornea’s activity. All these documents reflect in detail her oppositional activity and its international impact through the eyes of the secret police.

The 1987 anti-communist revolt of workers in the city of Braşov and Cornea’s display of solidarity with them represent a key moment not only for the oppositional activity of this prominent Romanian dissident, but also for the evolution of her files. After listening on RFE to the news about the revolt and its violent repression by the state authorities in November 1987, Cornea openly manifested her solidarity with those revolting against the regime. She displayed in front of her house a placard with a message declaring solidarity with them and drafted 160 manifestos that were spread with the help of her son Leontin Horaţiu Iuhas in various public spaces in Cluj (Cornea 2009, 194–195). The 1987 revolt in Braşov had a deep impact on the policies of the Securitate regarding Doina Cornea’s case. On 19 November 1987, she and her son were arrested and a detailed home search of her private dwelling was conducted by the secret police (Cornea 2006, 203). The documents concerning her arrest and interrogation by the Securitate, the manuscripts and drafts of her works, and the correspondence confiscated during the home searches of 19 and 23 November 1987 were archived by the Securitate in the “criminal file” created against her name and that of her son. Most of the documents of this file were created or gathered by the secret police in the period from November to December 1987.

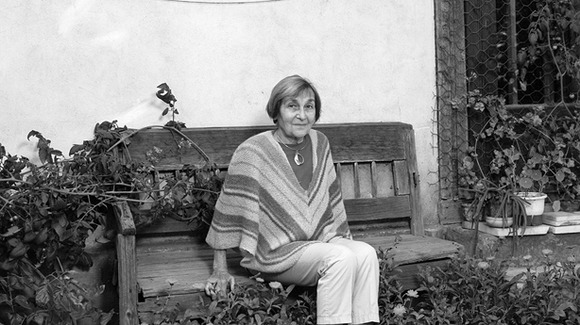

Among the documents confiscated during the home searches are the most valuable pieces of this ad-hoc collection, such as the draft of the first letter sent by Doina Cornea to RFE in July 1982, the drafts of the letters “About truth and how to resist the terror of history,” “What to is to be done? – or how not to render unto Cesar what belongs to God” [Ce e de facut? - Sau cum să nu dăm Cezarului ce se cuvine lui Dumnezeu”], and “Open letter addressed to the President of the State Council,” and handwritten copies of the manifestos of solidarity with the 1987 Braşov workers’ revolt (ACNSAS, P 000 014, vol. 2, ff. 62–66, 73–76, 109). These documents were archived by the secret police as proofs of Doina Cornea’s actions against the regime and were invoked during their interrogations of her in late November 1987. Besides these documents, the Securitate archived in the criminal file arrest warrants, minutes of the home searches, minutes of the interrogations, and various legal documents concerning the criminal investigation. At the end of December, Doina Cornea and her son were released by the Securitate due to the pressure of the Western mass media. Cornea’s case became internationally known due to the documentary film directed by Christian Duplan and broadcast in December 1987 by French television, which comprised also an interview with her (Deletant 1998, 249). Her internationally visibility was extended by the documentary film The Red Disaster, directed by the Belgian journalist Josy Dubié, which many Western television stations broadcast. This film showed Cornea as a small and fragile old lady confronting alone the ruthless dictator Nicolae Ceauşescu. This inspired image made her an iconic image for the equally fragile yet courageous anti-communist Romanian dissent. The Mother Theresa look-alike woman who was standing alone against Ceauşescu’s oppressive regime touched Western viewers. Although her words were not intelligible, she seemed to embody the nation’s redemption from a miserable and humiliating existence. In short, her image enhanced the message of the documentary and contributed to international grassroots solidarity with Romania. The interview in this documentary film and the open letter sent to Ceaușescu in September 1988 and broadcast by RFE conveyed her opposition to the so-called “rural systematisation,” a national programme promoted by Ceaușescu’s regime, which envisaged the demolition of more than 7,000 Romanian villages (Ceaușescu 1989, 395). Cornea’s critical statements against the “rural systematisation” inspired the collective initiative Opération Villages Roumains (OVR), “the largest ever network of transnational support against the abuses of Ceauşescu’s regime” (Petrescu 2013, 317).

The period of her arrest from November to December 1987 had a contrary effect on Doina Cornea’s attitude towards the regime than what was intended by the Securitate. After December 1987, her open letters became more virulent and dealt more with political issues than those before 1987 (Cornea 2009). Her intense and increasingly vocal oppositional activity from 1987 to 1989 caused a change in the strategy of the Securitate. Because her arrest caused protests from Western governments and mass media, the Securitate tried to completely isolate her and forced her practically into house arrest. Her phone connection was cut off. Militia and Securitate employees picketed her private dwelling day and night in order to prevent her contacts with foreign journalists or other Romanian dissidents.

Illustrative of Cornea’s isolation as dissident due to the strict surveillance of the secret police and the implicit limitation of her ability to convey any messages to the public is the way in which she managed to send messages to the conference organised by Solidarity in 1988 in Krakow, to which she had been invited by Lech Wałesa, though she was not allowed to go. Her text, written on a cigarette paper and hidden in the head of a handcrafted doll, was smuggled out of Romania by Josy Dubié, whom she met first by chance in Cluj. He not only assumed the trouble of carrying the message across the border, but also managed to double-cross the police later in order to interview Cornea for his highly critical documentary on Ceauşescu’s communism (Cornea 2002).

The intense Securitate activity to keep her activity under surveillance and monitor its national and international impact is largely reflected in the “informative surveillance file.” The reports of the secret police relate and analyse in detail the broadcasts of the Western radio and televisions stations dealing with Cornea’s oppositional activity. These documents represent a valuable source for how information warfare was carried on during the late Cold War period and what roles the Western radio stations and TV channels played in this conflict. Duplicates of many documents in Cornea’s “informative surveillance file” were integrated by the Securitate in the files of the so-called “Operation Ether” (Operaţiunea Eterul), a complex of strategies, plans, and measures conceived by the Securitate in order to prevent the oppositional activity of Radio Free Europe and its effects in communist Romania.

The custody of the Securitate files was officially transferred in December 1989 from the Securitate to the Ministry of National Defence, which kept them until 1990, when the Romanian Intelligence Service (SRI) was established. The SRI became the institution in charge of their custody and preserved the Securitate files (including those regarding Doina Cornea) until June 2001. According to the mentions made by SRI employees on the covers of the volumes of Cornea’s “informative surveillance file,” the file was officially closed on 23 September 1991 and was microfilmed in February 1996. From June 2001 to March 2002, the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives (CNSAS), the main institution in charge of carrying out transitional justice in post-communist Romania, gradually received them into its custody.

The Doina Cornea Ad-hoc Collection at CNSAS illustrates on the one hand the variety of surveillance techniques and strategies of intimidation used by the Securitate during 1980s in order to prevent or stop any act of resistance to Ceaușescu’s dictatorship, and on the other hand the complexity and uniqueness of Cornea’s cultural opposition activity. The files created by the Securitate on Doina Cornea represent a veritable inventory of the most important surveillance techniques and strategies of intimidation used by the Securitate during the 1980s in order to prevent or stop oppositional activities. Taking into account its evolution it is also a barometer of the increasingly repressive character of Ceaușescu’s regime during 1980s. However, the failure of the secret police to stop her oppositional activities despite mobilising such a wide-ranging repertoire of techniques suggests that the repressive apparatus was not as infallible as its image in the post-1989 Romanian collective memory would suggest.

The uniqueness of her case lies in her ability to use transnational networks in order to pass her messages to the West and from there to reach her fellow citizens through the RFE broadcasts. This ad-hoc collection is a valuable historical source for reconstructing these networks, but also for researching the process of drafting the open letters authored by Doina Cornea. The collection comprises the first drafts of the letters sent by Cornea to RFE from 1982 to 1987. By using the networks mentioned above, she succeeded in conveying her vocal criticism of Ceaușescu’s absurd policies not only to a local audience, but also to an international one. Due to her international visibility, she was able to attract the attention of Western governments and mass media to the abuses and human rights infringements of Ceaușescu’s regime. She used this visibility not only to promote her oppositional agenda, but also to bringing to the fore other critical voices among those opposing communist regime in Romania. Due to her coherent and stubborn opposition to Ceaușescu’s regime, she became a role model for those very few who “did not give up thinking with their heads” and followed her path of opposing dictatorship.