The history of this collection is closely linked to the professional career of Mihai Stănescu, the creator of the most well-known cartoons of a political nature in the last decade of Romanian communism. Mihai Stănescu’s profile as a draughtsman and cartoonist began to take shape in the 1970s, after a long institutional apprenticeship, beginning with high school followed by the Institute of Fine Arts and continuing with a number of years of experience in advertising graphics. The same decade also saw his debut in the “satire and humour” magazine Urzica (The nettle), the most prestigious cartoon magazine of the day, founded in 1949 on the model of the Soviet magazine Krokodil. It was a debut that rapidly brought him fame. Thus by the mid-1970s, Mihai Stănescu was effectively a freelancer, living on what he made from the sale of his works. He received a minimal income from a collaboration with Fondul Plastic (the Union of Visual Artists retail outlet), for whom he designed postcards. It was in the 1980s that, on the one hand, Mihai Stănescu’s nonconformist art as a cartoonist received both national and international acclaim on a number of occasions, while on the other hand, it aroused a harsh reaction on the part of the communist authorities. Thanks to his international success, he managed to supplement his income with variable and occasional sums of money from prizes awarded at various competitions. In the course of the 1980s, Mihai Stănescu states that he won between thirty and forty prizes. Frequently the money was not sent to him in Romania, so, he says: “I went on hunger strike or something and they allowed me to go to the festival and collect my prize.” Regarding the consequences at the national level of his international fame, Mihai Stănescu recalls the manner in which his first book was received by the communist authorities: “I behaved like a free person, meaning that I drew what I wanted, they didn’t publish them, I went with them in a briefcase, and I showed them to people in the street. I won a prize in Japan in 1982, in Japan, where there had been about 10,000 competitors. They praised me in the press in this country too. Immediately after I returned, I brought out a book, an album that had no title – it was just called Mihai Stănescu. I took advantage then, because Ceauşescu had just decided that there was no more censorship, that each institution was responsible for what it did. And I immediately brought out the book; I went to the Union [of Visual Artists], we signed for it, printed it at our printing workshop, and sold it at Fondul Plastic. At the launch, at the House of Art, there were five people (me, two girls, and the Dinescu family). The next day, people found out and began to buy it,” relates Mihai Stănescu. And he adds, regarding the consequences that he had to bear on the part of the communist regime: “About four days later, the minister of culture, Mrs Suzana Gîdea, found out, and she banned it, issued punishments at the Artists’ Union, punished those who had signed for it. They couldn’t do anything to me, because I had already won a prize abroad and they had just been praising me. But the police [the Militia] came to my home, opened the door, entered in my absence, and looked for books. This album was printed in 5,000 copies; 4,000 were sold in four days and 1,000 were withdrawn. They handled things badly, because the book was reproduced all the same, and I became famous.”

With the withdrawal from public circulation of those 1,000 copies of his debut volume, the subversive potential of Mihai Stănescu’s creations was identified, and the Securitate entered him in its files. A surveillance document issued by the Securitate, which Mihai Stănescu himself published in one of his post-1989 volumes, mentions that: “With the approval of the Party structures, on 18 May 1982, he was put under observation, it being pointed out that during his journey of January 1982 to Japan, where he was invited to be awarded the grand prize won at an international cartoon competition, he gave an interview for the Tokyo newspaper Yomiuri, in the course of which he made negative statements with regard to the economic situation in Romania. In April 1982, under the aegis of the Union of Visual Artists, he published a volume of cartoons, in which some drawings were of an interpretable character, so that the Council for Socialist Education and Culture ordered its withdrawal from sale. The publication of the album generated a series of negative comments on the part of artists, specialists, and other persons. Some drawings taken from the album were published in France and Britain, and the radio station Radio Free Europe, in its broadcasts, made comments on the event and the artist” (Stănescu 2009, 24).

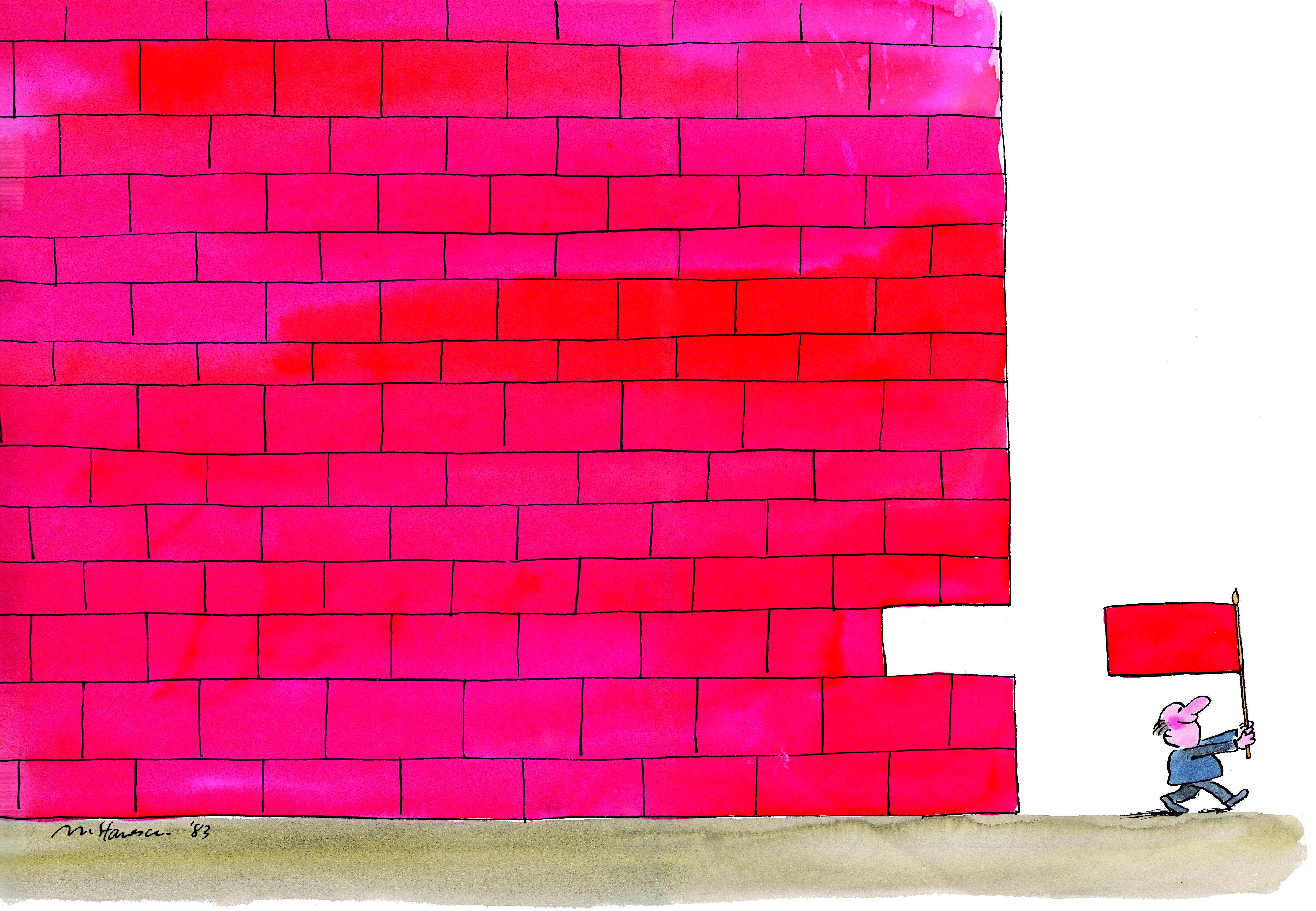

After this episode in 1982, Mihai Stănescu was to face continual problems on the part of the communist authorities, with more and more serious consequences for his albums, whose publication could no longer be easily approved. In 1985, another album of his was banned, this time even before leaving the printers: “In 1985, I tried to make another book called Umor 50% (Humour 50%), because there were cuts to heating, food, gas, everything, and I said that cuts would have to be made in humour too. It was printed, but it didn’t get as far as leaving the printers,” recalls Mihai Stănescu. The album began with one of the remarkable items in the collection, the cartoon entitled “Flag-wall”, which depicts a little man pulling a symbolic brick from the base of a wall of red bricks to make a red flag, a Communist Party flag, with which to go proudly straight to the march, while behind him the wall, deprived of a solid foundation, is about to collapse. The improvising of a flag from a brick of the wall satirises, on the one hand, the shortages of the last decade of communism, when many objects that could not be found in shops were improvised from other objects made for other purposes. On the other hand, it is a very subtle criticism of the forced mobilisation for marches on 1 May and 23 August, the national day under communism. Read from a post-communist perspective, it is a premonitory allusion to the collapse of communism precisely because of these shortages, which the cartoon suggests have come to erode the ideological symbols of the Party. The same volume includes a series of cartoons showing a shipwrecked man on an island waiting for a ship to rescue him. The ship is named Future, and it is seen from the island in inverse perspective, getting smaller instead of larger as it approaches. Quite transparently, this drawing is a criticism of the fact that the luminous future promised by communism had become ever darker in the Romania of the 1980s. Here are the terms in which the communist officials spoke of the initiative and of the context in which Mihai Stănescu wanted to publish this 1985 album of cartoons: “On 31 September 1984, Stănescu Mihai left for the USA, as the beneficiary of a thirty-day scholarship offered by the American state, which gave him the possibility a further month after the scholarship, bearing the resulting costs. […] Returning from abroad, he busied himself with the publication of a new album of cartoons. On his presenting the works for this album to the leadership of the Union of Visual Artists, a part of them were rejected. This was communicated to him and he was given the works so that he could take those approved by the Council for Socialist Education and Culture (CCES) for counter-approval. Taking advantage of this occasion, he introduced among the approved works also those that had been rejected, and presented them to Comrade Secretary of State Hegeduș Ladislau at the CCES, who approved them all. On finding out about this manoeuvre, the vice-president of the Union of Visual Artists, Mărginean Viorel, forbad the publication of the album, appreciating that the artist’s action was an act of professional indiscipline” (Stănescu 2009, 44).

In 1989, he had yet another book banned, Acum nu e momentul (Now is not the time), although in the meantime he had published in France Rire en Roumanie, which he tried without success to smuggle into Romania, as he recounts: “When I saw that I was banned, I began to send my books through friends at the American embassy, and they were published in France. In 1988 I went there too; I spoke on Radio Free Europe; I said what came into my head. I arrived here with eleven copies of my book, which was called Rire en Roumanie, and they confiscated all the books at the border, at Arad. The train was ready to leave and the police shouted beside the train: ‘Which one is Stănescu?’ I got out of the train and said: ‘I am.’ ‘Aren’t you ashamed of yourself? We have orders to confiscate the lot, because you talk there.’ And I was left without books. […] I also created an album called Now Is Not the Time in June 1989, and I multiplied [the drawings] at the American Library, at the Fine Mechanics Factory, where they had photocopiers. And that’s why people knew about it, and after the Revolution the first book that appeared in Romania was mine, at the beginning of January, because all the writers had withdrawn their books, to remove from them the compromises that they had made. I had mine ready and I had nothing to remove, so [I took advantage of the fact that] the whole House of the Spark was free, and I printed [the album] in 100,000 copies.” Already in 1989, the volume had been send over the border to France, where it had appeared in the same year under the title C'est pas le moment. In Romania, the huge print run at the beginning of 1990 immediately sold out, while Mihai Stănescu’s exhibitions were a great success. Speaking of the eternal significance of the volume Now Is Not the Time, the drawings that Mihai Stănescu multiplied by his own means during the last year of communism in order to circulate them clandestinely among acquaintances, the writer Octavian Paler, one of the leaders of opinion in Romania, observes in his foreword to the volume: “And I remember how he would walk about at the seaside, through the hall of the Writers’ House at Neptun, with a bag containing, wrapped up, a subversive book, this one, ready to be sent to France, to be printed there, because here ‘it was not the time.’ In fact no one suspected that Mihai Stănescu had the impertinence to walk about at Neptun, just a stone’s throw from the ‘reservation’ of a dictator who had no taste for irony, with the corpus delicti of his intended recidivism, given that he had published a book in France before. I found out after he held the package out to me and asked me to look, alone of course, at his drawings. I went to my room and I understood from the cover that Mihai Stănescu was determined to remain himself, not to retreat, not to share in the ravages of wisdom, to be inconvenient and inopportune. In fact, the great value of this artist with the allure of a man of the world starts from his inopportunity. At a time when prudence had become a form of complicity, he took the admirable liberty of mocking those who banked on our fear. And I would permit myself to draw attention to one detail. Now everyone proclaims their hatred of the dictatorship. Mihai Stănescu’s drawings may seem, from this point of view, almost conformist. But look at them with the eyes with which I looked at them in August 1989, when no one knew whether there would ever be an end to the nightmare through which we were fumbling, waiting for a miracle that seemed to get more remote the longer we waited for it. Then you will understand better, I think, how grave is the seriousness behind Mihai Stănescu’s smile.”