The current collection, the Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur Ad-hoc Collection, was defined by separating it from the collection of judicial files created by Soviet Moldavian KGB concerning persons who were subject to political repression under the communist regime. The Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur group, or National Patriotic Front, is a significant example of ethnic Romanians’ resistance to the Soviet “nationalities policy” in the MSSR. This group appears to have been the only well-structured oppositional organisation in the MSSR in the post-Stalinist period. Its members formulated clear-cut demands, spelled out in numerous documents produced by Alexandru Usatiuc and, in particular, Gheorghe Ghimpu. Those documents were critical of the Soviet regime and suggested that the situation could be changed via the unification of formerly Romanian territories with Romania. The leaders of this group argued that, since the USSR and Romania were communist countries, their initiative had a chance to succeed, provided that Ceauşescu agreed to negotiate with Moscow. In this context, it appears that the group’s activities were directly linked to the post-1968 context and, more broadly, to what Amir Weiner astutely calls the “socialist irredentism” of the Soviet satellites (Weiner 2006, 164). The Soviet authorities had been anxiously observing the policy of the Romanian authorities at least since early 1964, when the first intimations of Romania’s allegedly independent stance in foreign affairs were discernible. Soviet security concerns framed this vision of the Romanian leadership’s policy, although the irredentist claims in the official Bucharest’s position were rather marginal. This exaggerated apprehension of the timid Romanian irredentist claims was especially strong among the leadership of the MSSR, who felt threatened by any intimations of “local nationalism.” Fears concerning the stability of western frontier areas (including the MSSR) only increased following the Prague Spring and Romania’s apparent defiance of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968. This context both prompted the articulation of Usatiuc and Ghimpu’s “national dissident” message and augmented the fears of the Soviet authorities, who resorted to repression against “local nationalism” in the western republics, notably in the Baltic republics, Ukraine, and Moldavia.

Judging by the documents in the collection, the leaders of the National Patriotic Front did not question the nature of the communist regime, but rather the legitimacy of Soviet rule in Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina. Anti-communism was merely an implicit dimension of the National Patriotic Front’s programme. However, given its nationally inspired message, the Soviet regime perceived this organisation as a real danger, with nationalism being the main count of indictment. Although the members of the organisation were demanding the unification of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina with Romania, in the final verdict the Soviet regime emphasised the organisation’s intention to “break the MSSR and part of Ukraine away from the USSR.” The group’s members were viewed as extremely dangerous because they were vehemently contesting several myths and implicit principles of the Soviet nationalities policy as applied to the MSSR, notably the existence of an independent Moldavian nation and of a distinct “Moldavian” language, as well as the cornerstone idea of the Soviet nationalities policy epitomised by the slogan of “equality among nations.” All the main members of this “anti-Soviet” organisation condemned the policy of Russification and ethnic discrimination to which the Moldavians were allegedly subjected by the Soviet authorities. This organisation fits the pattern of the other dissident movements at the Western Soviet periphery. This was obvious both from the nature of its oppositional message, expressed in strong national terms, and from the way in which its members manipulated Soviet legislation during the trial and appealed to foreign audiences (notably the UN and Radio Free Europe).

The materials in the collection fit into two main categories. First, it features the documents produced by the members of the National Patriotic Front before their arrest by the KGB, including various memorandums and open letters addressed to foreign audiences (the Romanian communist leadership, Radio Free Europe, or the UN). The bulk of the surviving documents were confiscated by the KGB during searches of the suspects’ apartments immediately before or after their arrest. Unfortunately, some of the most interesting documents in this category have not survived. They were either lost or subsequently destroyed by the KGB. This is the case of the most important and comprehensive policy statement produced by the members of the National Patriotic Front – the report of the First Congress of the underground organisation. According to the memoirs of Alexandru Usatiuc, its founder and main leader (Usatiuc-Bulgăr 1999), the congress took place in 1967 and did not have a traditional format, which means that it was not a simultaneous meeting of all its members, but a series of meetings in small groups, which were subsequently summed up in a programmatic document. This is how Usatiuc depicted this moment in his memoirs, recorded by Serafim Saka in 1995:

”Those were hard times and we held the congress over time, so to speak, and through groups of four to five people. We also had an eighty-four-page report, published a decision, an instruction, and so on. The decision focused on reunification with Romania, demanded the establishment of Romanian as the state language, and proclaimed the tricolour as the national flag, which should have a black ribbon attached alongside the three colours until reintegration. We advocated the introduction of the Latin script, of the Romanian anthem and coat of arms. But none of these demands could have a significant echo here in Bessarabia, which, at that time, was very Soviet” (Saka 1995, 114).

However, according to an interrogation held at the KGB in 1972, the First Congress of the National Patriotic Front took place in late 1969 to early 1970. The Congress’s report allegedly reviewed the history of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, and estimated the number of Romanians who had lived on those territories but had been exterminated by the Soviet authorities. It also emphasised the policy of Russification of the native population pursued in Bessarabia by the Russian empire and continued by the Soviet Union. To compile the report, the Front's members apparently used such sources as textbooks of Romanian history published before 1940, the book by Ştefan Ciobanu 106 ani sub jugul Rusesc (106 years under the Russian yoke), and Karl Marx’s work Notes on the Romanians, which had been translated into Romanian and published in Bucharest in 1964.

Another important document not accessible to current researchers and most likely destroyed by KGB operatives was the memorandum that Usatiuc intended to present to the Romanian communist leader Nicolae Ceaușescu in 1971. This document summarised the political views of the Front’s members and called for Bessarabia’s and Northern Bukovina’s unification with Romania. It also demanded Romania’s direct involvement in the “Bessarabian question,” including through such means as a military intervention, provided that the Soviet–Romanian negotiations would fail.

Despite the loss of these documents, a number of similar materials are still in existence. These served as the main basis for the group’s indictment. Among these, several memoranda addressed to Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty are especially significant. Both the members of the Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur group and the Soviet authorities were aware of the impact of the station’s broadcasts on the population of the Soviet Bloc. It is clear that the Soviet secret services were alarmed by the potential influence of the RFE/RL broadcasts on the citizens of the USSR and the satellite states, so the radio station’s “subversive activities” were taken rather seriously. In the context of the interrogations of the group members, KGB officials noted that “during the last five years” (i.e. after 1967) the RFE intensified its activities with the purpose of “subverting the unity, cohesion, and friendship between the peoples of the USSR and those of the other socialist countries, fomenting nationalism, inciting tendencies towards emigration, and spreading anti-Soviet hysteria.” During 1968–71 the RFE/RL broadcasts were allegedly paying increasing attention to the “Bessarabian question,” mentioning Romania’s “purported claims to the territory of Soviet Moldavia and the rebirth of nationalist tendencies within the [Moldavian] republic.”

Among other documents produced by the group members, one could emphasise their personal letters and notebooks, which were excellent illustrations of their ideas and personal trajectories, providing a glimpse into the initial formulation and gradual crystallisation of their “subversive ideas.” For example, Valeriu Graur’s personal notebook provided ample information on his contacts with suspicious persons during his frequent trips to Romania in the late 1960s, especially with surviving leaders of the early twentieth-century national movement in Bessarabia, such as Pan Halippa and Gherman Pântea.

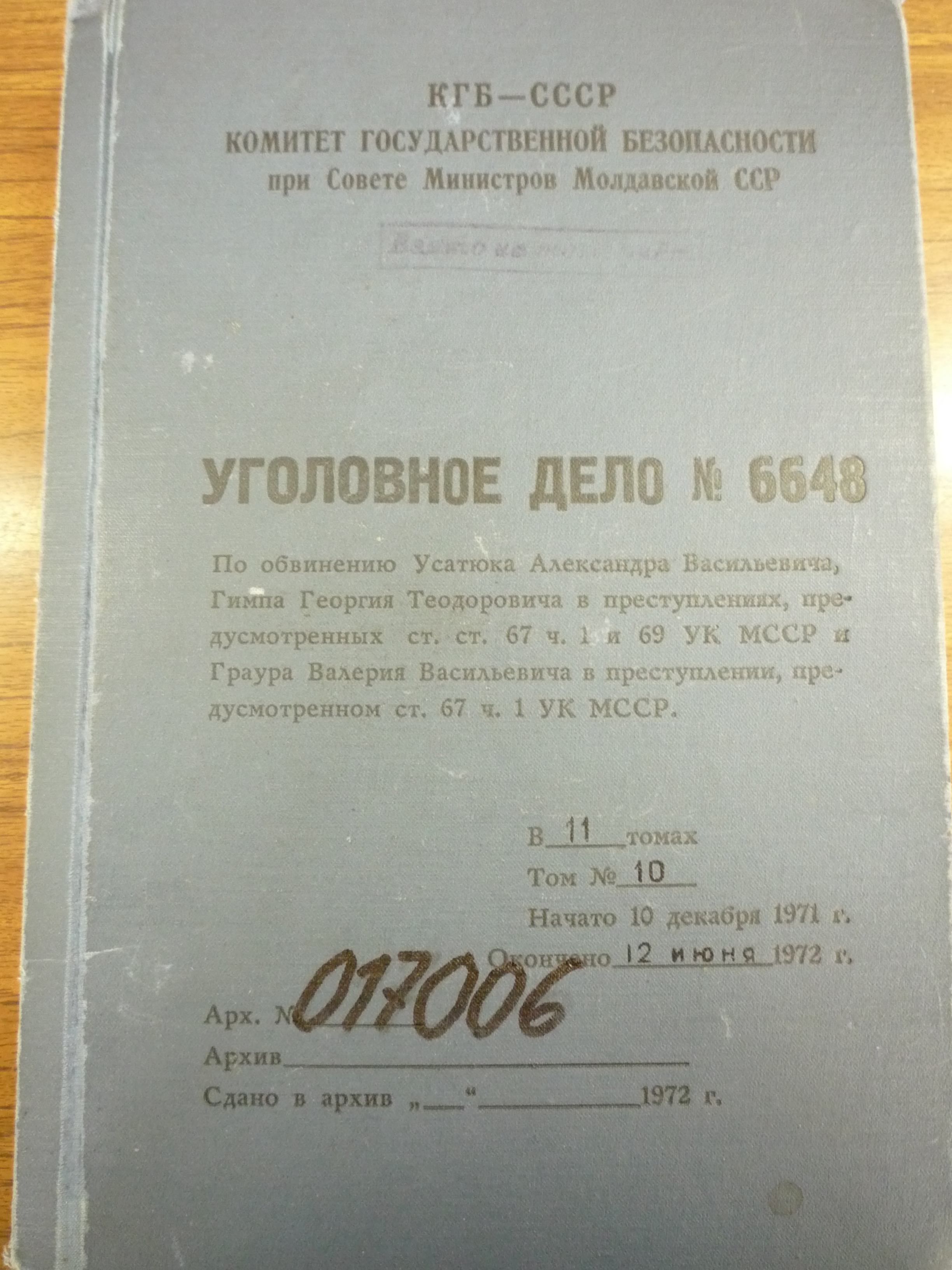

A much larger share of the collection’s documents consists of interrogations and testimonies provided by the group members after their arrest, from which only those assumed more or less willingly by the accused were selected. Although produced under pressure at the KGB headquarters, these signed testimonies can be regarded as valuable sources of information on the activities of the organisation. Above all, these documents bear witness to the existence of other materials related to the Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur group, which were originally discovered during the search at the homes of the three members, but are currently missing, because the KGB either did not preserve or did not release them. Most of these testimonies were given between late January and June 1972. The main defendants provided a detailed account of the foundation, evolution and main aims of the organisation. The KGB officials were especially interested in tracing the links between the group members, particularly between the three main protagonists – Usatiuc, Ghimpu, and Graur. The accused carefully reconstructed the story of their meetings, their contacts and the circumstances of the production and elaboration of the confiscated incriminating materials (memoranda, diary notes, personal notebooks, correspondence, etc.). According to the investigation carried out by the Soviet Moldavian secret services, both prominent leaders of the organisation, Alexandru Usatiuc and Gheorghe Ghimpu, shared to a large extent the same views regarding its programme and main objectives. However, Usatiuc and Ghimpu had different approaches to the tactics of rebuilding the state unity of Romania. Ghimpu advocated the separation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina from the Soviet Union and their unification with Romania as simple provinces. Usatiuc believed that these territories should first gain their independence from the Soviet Union and create an independent state named the Moldavian People’s Republic, while unification with Romania should take place later, as a second stage of a more protracted process. These nuances proved to be irrelevant for the KGB investigators, who based their accusation on the organisation’s intent to “sever the Moldavian SSR and part of the Ukrainian SSR from the Soviet Union.”

The Supreme Court of Justice of the MSSR completed the hearings in the case on 13 July 1972, sentencing the main leader of the National Patriotic Front, Alexandru Usatiuc, to seven years in a high-security labour correction colony in Perm’ and to five-year exile in Tyumen. Gheorghe Ghimpu was sentenced to six years in a high-security labour correction colony. Valeriu Graur was sentenced to four years in a high-security labour correction colony.