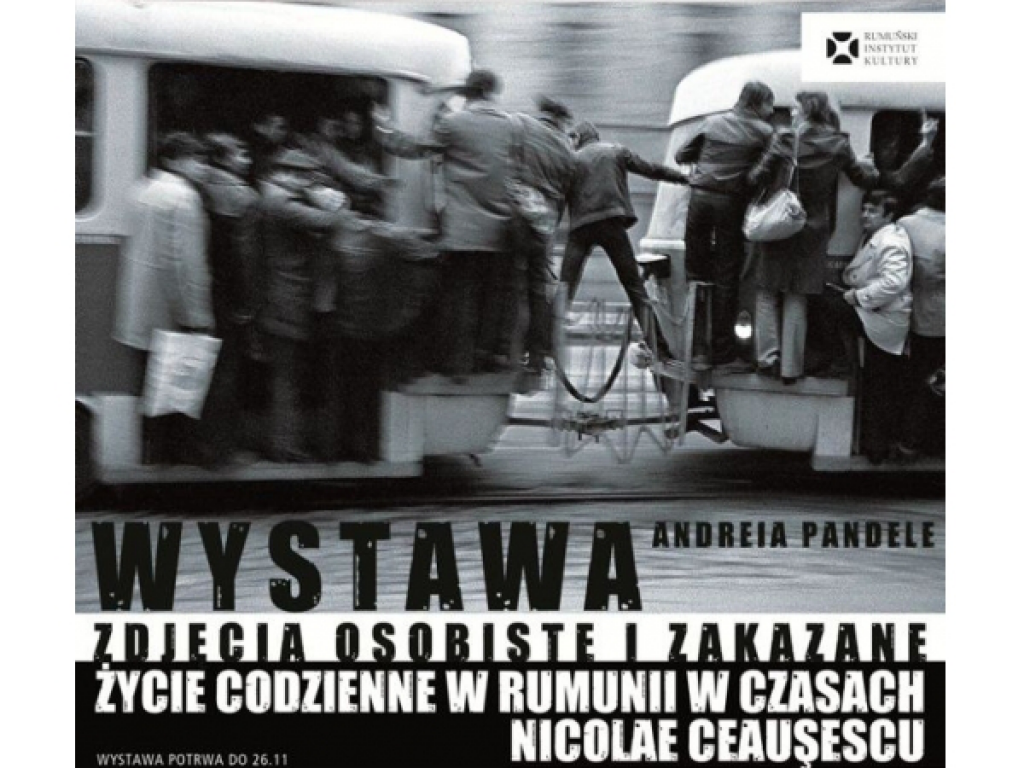

“At first, I tried to take photographs of the landmarks of the city that was going to disappear. Being an architect, I had a good idea of what was going to be done, of what would follow. I had, let’s say, a small head start, and I took some photographs that came out incredibly well compared with what I was expecting. That must have been about 1980 or 1981. Of course I had heard previously what they intended to do. Then it wasn’t long before I understood that what was going to happen was extremely serious: that our cultural heritage was being destroyed, that the support of our memory was being wiped away. The people whose houses were being demolished seemed terrorised, you know – the framework of their lives was being destroyed, their lives were being destroyed. And equally bad, I realised that everyday life had become a test of endurance, as aberration step by step replaced normality.” So Andrei Pandele describes the beginnings of a quite special passion, thanks to which his personal photographic archive is, very probably, the most generous of all those that gather the memory of the demolitions carried out by the communist regime in Bucharest in the 1970s and 1980s, and of everyday life during that period of decline and crisis. The photographs that make up this thematic collection about the demolitions in Bucharest and daily life during communism were preceded, and then alternated with another sort of snap-shot, which helped Andrei Pandele to perfect his photographic technique and at the same time to skilfully camouflage the moments in which he took pictures that would be uncomfortable for the Ceaușescu regime. To begin with, Andrei Pandele was a sports photographer – one of the most well-known and best in the last decades of communism, and indeed for a long time after the fall of the communist regime. Nowadays it is a normal thing to take photographs at any moment, thanks to the miniaturisation of cameras and especially the possibility of taking pictures with a mobile phone, which is always at hand. In the 1970s and 1980s, cameras were relatively large and were generally used on holiday to immortalise happy moments with friends and family. At the time it was very unusual to take pictures in cities, unless one was a photo-journalist. In this context, Andrei Pandele could camouflage his taking all these pictures in the streets of Bucharest behind the fact that he was always carrying a camera to various sports events anyway. “Alongside my passion for architecture,” relates Andrei Pandele, “I also have a passion for sports photography. Officially, I have been sports photographer since 1969. I generally took such photographs on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays, or at special matches. Well, this meant that I often went about with a camera on me, round my neck, so to speak. It looked unusual back then, and indeed it was, at first. But the fact that I was repeatedly seen at sports events made it normal for me to be accepted like that – always with a camera on me. It wasn’t long before no one was surprised to see me like that.”

The photographs that record the techniques of destruction and the areas of the old centre of the city of Bucharest that vanished under communist bulldozers were not just “grabbed” at random, but followed a coherent plan, as Andrei Pandele explains: “I wanted to record the life of the city, against the background of the urban landmarks that were threatened with destruction. As I was interested in the mutilation ‘works’ and in their effect on the inhabitants of the area, I returned a number of times and tried to fix direct impressions on film.” As a consequence of this plan, Andrei Pandele systematically and in real time photographed the central area of Bucharest that was subjected to “rearrangement” operations, as they were termed in the neutral communist jargon, which avoided the use of terms with negative connotations like “demolition”, not to mention “destruction.” He returned dozens of times each year and took dozens of photographs in these thematic series, with the result that his collection documenting both the communist demolitions and the everyday life of that period grew organically from 1980 onwards. From his entire photographic career, Andrei Pandele has some tens of thousands of images, including, somewhat concealed, those in the series mentioned above: “I used more than a hundred films per year, the great majority black and white, and on each film there would be one, two, maybe three images of this sort: communism, brutalisation, everyday life during communism, demolitions. Over the course of almost a decade, there were several hundred photographs of this type.”

From a thematic point of view, the metamorphoses of the urban landscape of Bucharest constituted the skeleton around which Andrei Pandele built his collection. As he recalls, the images were initially gathered on aesthetic grounds, and then gradually became testimonies to the disappearance of historic districts and buildings and the appearance of the hideous communist constructions. “At first I went at random. Later I began going to photograph areas that I had targeted as they seemed to me more suitable for photographing. Sometimes I wrote down, when I arranged them at home, the streets where I had been – Saturday, Sunday. There was a particular street that was very appealing from a photographic point of view and which I liked very much. It was called Strada Ecoului [Echo Street]. I liked it because part of it almost went in a zig-zag. It wasn’t straight. In the part where there was that zig-zag there were some houses of high quality. The light fell very well there. A splendid street for me and for what I intended to do in a photographic sense. But at a certain moment, all landmarks disappeared. At first I knew where I was going – there were houses, shops, buildings that I was familiar with. And then suddenly you were in a desert, with huts [for the construction sites] in a foreign place. It was as if you no longer knew where you were, although, physically, you could tell. But any story, any familiar context had been done away with. I took photographs of those empty places and, in the photographs, it was as if I no longer knew where I was. […] In the photographs the places become unidentifiable, or very hard to identify. […] It’s with difficulty, sometimes with great difficulty, that we can tell precisely where some photographs were taken. What exactly was there; what exactly had been there.” So Andrei Pandele recalls the landmarks of his photographic experience, which had not only a professional dimension, but also an existential-emotional one.

Initially, Andrei Pandele had problems with the communist authorities because the places in the centre of Bucharest where the demolitions were carried out during the last communist decade were very strictly guarded and supervised. The mere act of taking photographs during the demolitions could not constitute an offence against communist legislation, so those who did this could not easily be arrested. However the communist authorities did not tolerate such activity because the few dissidents in 1980s Romania were using foreign radio stations to publicly criticise the Ceaușescu regime’s policy of destroying cultural heritage, and foreign journalists visiting Romania were interested precisely in this policy which, unlike any other, could not be concealed in any way: anyone who visited Bucharest could immediately notice the bulldozers and demolition sites that dominated the centre of the city. In this connection, Andrei Pandele recalls: “At first, in the first months when I took photographs of the landmarks of the city, I was stopped by the Militia several times. I was doing nothing illegal in taking photographs, but in their eyes I was doing something dubious. It was not forbidden to photograph Bucharest, but to do such a thing in the demolished areas was not viewed at all positively. I know a lot of people who were held for hours, whose film was taken out of their cameras for an act of this sort.” Andrei Pandele thus had to develop a technique of going unnoticed while he was taking photographs: “It was all the more difficult to pass unnoticed when you were, like me, almost 1.90 metres tall. I couldn’t hide, but I could do something, or rather pretend to be doing it while in reality doing something else. Well, that was the case with many of the photographs in these thematic series. I practised taking photographs without holding the camera to my eye. I failed with a lot of pictures, but plenty did come out well under these difficult conditions.” On top of this, Andrea Pandele had the cover provided by his sports photographer’s card. For all that, what many times saved from destruction the pictures he took in strictly supervised places was the presumed protection of individuals in the hierarchy of the Interior Ministry. The protection, in essence abusive, of such figures in the communist elite, who were in a position to cause trouble for subalterns who “upset” their protégés, was essential for those who tried to do something on the edge of legality. This applied equally whether someone wanted to do something for their personal good, for example procuring products on the black market that could not be found otherwise, or for the common good, for example immortalising for future generations images of a historic city about to disappear. As Andrei Pandele recalls: “With the authorities – I may as well admit – I was lucky. They stopped me frequently in the first years, but they couldn’t find anything out of order about me. And there was something else. I taught a course in advanced photography. And the photographer from the Interior Ministry magazine […] whom I knew quite well gave me three names – the names of one major and two lieutenant-colonels. They were people in the Militia who did training. If I mentioned those names, the men on duty in the street would freeze. It was a great protection, a reference to a ‘contact’ that was of use to me.” And in the same connection, he adds: “And even if a Militia-man did stop me sometimes, I was covered by my sports photographer’s card. Together with the “ins” I mentioned earlier, this too, my status as a sports photographer, frequently simplified things.”

In many of his photographs, people appear. The reactions of many of them when they saw the camera were not of the most positive. Andrei Pandele recalls his experience of taking snapshots of everyday life: “They generally reacted badly. They didn’t feel very comfortable about appearing in photographs. Let me tell you something: I was working at the House of the People [today the Palace of the Parliament], and I came from Drumul Taberei district, where I lived, to work. I came by trolleybus, got off at the University, and went on foot to the House of the People. At a certain moment, somewhere around Children’s Romarta [shop – today the head office of BRD–Société Générale], in December, I took some pictures. It was raining. I was holding the camera under my coat, so it wouldn’t get wet. I continued towards my workplace and, at a certain moment, I noticed that I was being followed by three Militia-men and a woman ‘comrade.’ She pointed towards me and said: ‘That’s the spy, that’s the spy.’ […] Suspicion counted for a lot in those days,” Andrei Pandele emphasises. The collection that he had begun to capture the degradation of the last years of communism continued to grow after the fall of communism too. Andrei Pandele is still taking photographs that speak of the urbanistic and architectural suffering of Bucharest. He is of the opinion that: “the seeds of the uglification of Bucharest sown during communism are even now, unfortunately, bearing fruit. Agreed, my photographs are pictures that concern the past, our recent history. But they also have a certain present, they have dismal echoes even now, in our time. Unfortunately…”