The collection presents an example of local protests and civic self-organisation against environmental pollution, which was generally considered ideologically suspect and subversive by the Yugoslav authorities in the 1980s. The expectation was that ecological problems would be solved exclusively within institutions, and not on the streets (Oštrić 1992, p. 85), so protests were unacceptable in principle. However, in the spirit of self-government, goals could be achieved by using them. This is illustrated by the media coverage and archival documents in this ad hoc collection, which combines documents from two archival collections in the Croatian State Archives in Zagreb: the records of the Parliament of the Socialist Republic of Croatia and press clippings from the newspaper publishing house Vjesnik.

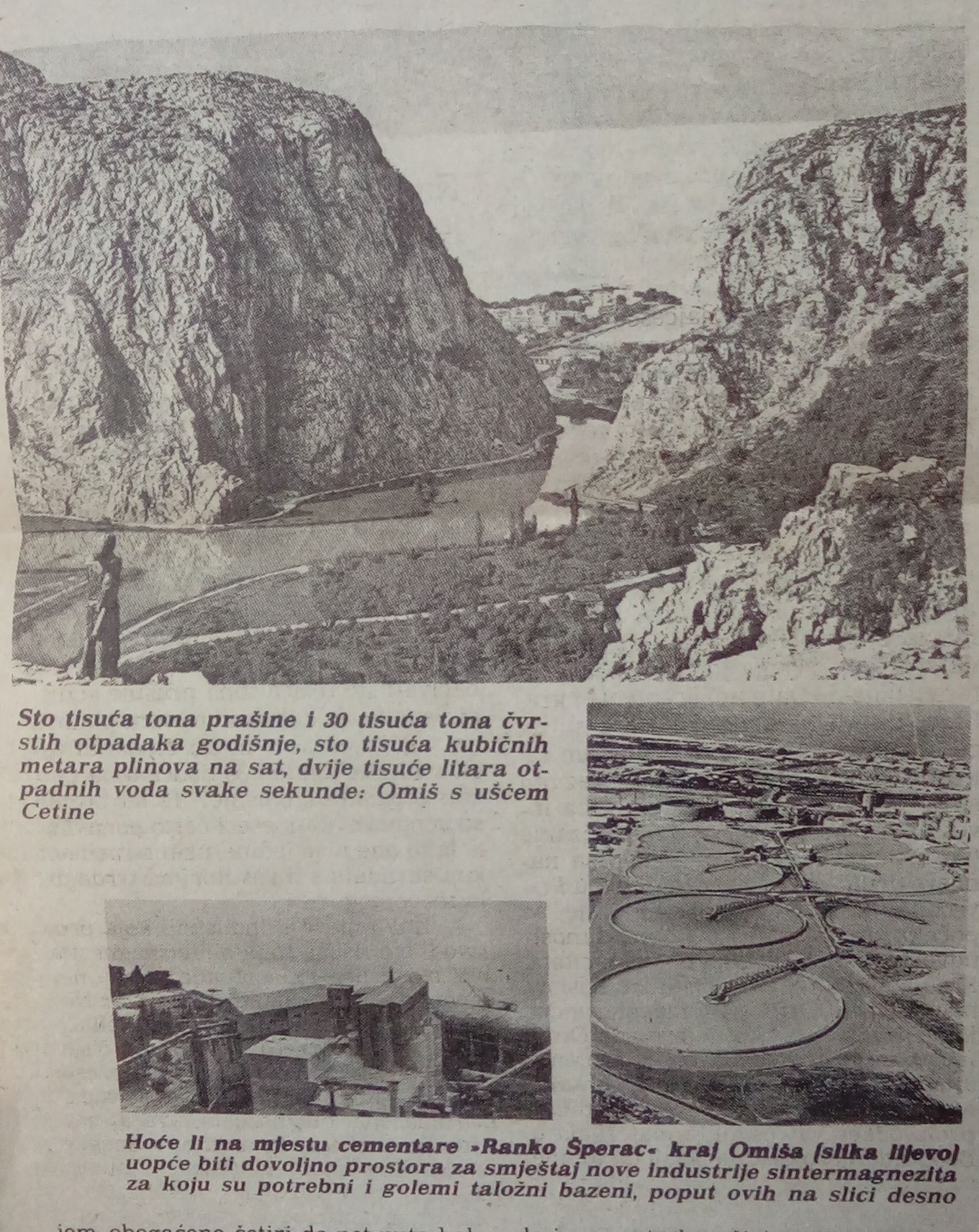

Omiš is a town in Croatia, located in the Dalmatia region at the mouth of the Cetina River into the Adriatic Sea. Since the early 20th century began, it has experienced more intense development as a centre of industry and tourism. The Kraljevac hydroelectric plant (in 1912) and several factories were built in this period, including the cement factory in Ravnice, 2 km south-east of Omiš (in 1908). Although changing owners and names several times, the factory produced cement until 1983. After the Second World War, since 1946, it operated under the name Renko Šperac cement factory, and in 1957 it was merged with all other Dalmatian cement factories, and an asbestos factory, into the single conglomerate Dalmacijacement (Žižić and Marasović 2014, p. 41). Due to low capacity and high production costs since the mid-1970s, the factory incurred losses, and Dalmacijacement formulated a project to transform the existing factory complex by setting up new operations entailing the production of sintered magnesia by using seawater, i.e., obtaining magnesium hydroxide from seawater. The size of the project is illustrated by fact that Dalmacijacement projected annual production of 100,000 tonnes, while the total global production of sintered magnesia at the time was approximately 300,000 tonnes per year. It is a raw material mostly used in the production of basic refractory materials, essential to heavy industry, especially for blast furnaces in steel production. The planned production technology consisted of adding limestone or dolomite to seawater, thereby inducing sedimentation of magnesium hydroxide – a semi-finished product from which sintered magnesia is derived by firing it in kilns. That process also includes neutralisation of seawater alkalinity with sulphuric acid. The Omiš Municipality endorsed the project and incorporated it into its long term development plan. On the other hand, the project was met with strong resistance by the local population. Through appeal letters to municipal and republic-wide governing bodies, local referendums and public demonstrations, they articulated strong opposition to the project's implementation, including construction of a pilot installation and its trial operation. They continually issued warnings about the potential harm to sea life, as well as pollution from gaseous emissions, dust and solid waste.

During a town meeting held in Omiš on 6 April 1979, the decision was made to stand against construction of the sintered magnesia factory and against any similar dirty industry factory “vigorously and forever.ˮ In six points, citizens demanded observance of the constitutional principles on environmental protection and prevention of activities that could give rise to pollution and endanger the health of citizens (Article 87 of the 1974 Constitution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia , Article 121 of the 1974 Constitution of the Socialist Republic of Croatia). Instead of a factory, they proposed the construction of a hotel complex in that area. They claimed that in principle they did not oppose industry and construction of a factory, “but such that they shall not harm the development of tourism, for which there are exemplary conditionsˮ (HR-HDA-1081. Parliament of the SRC. 13.3. Cabinet of the Parliament's President, File no. 3076/1979).

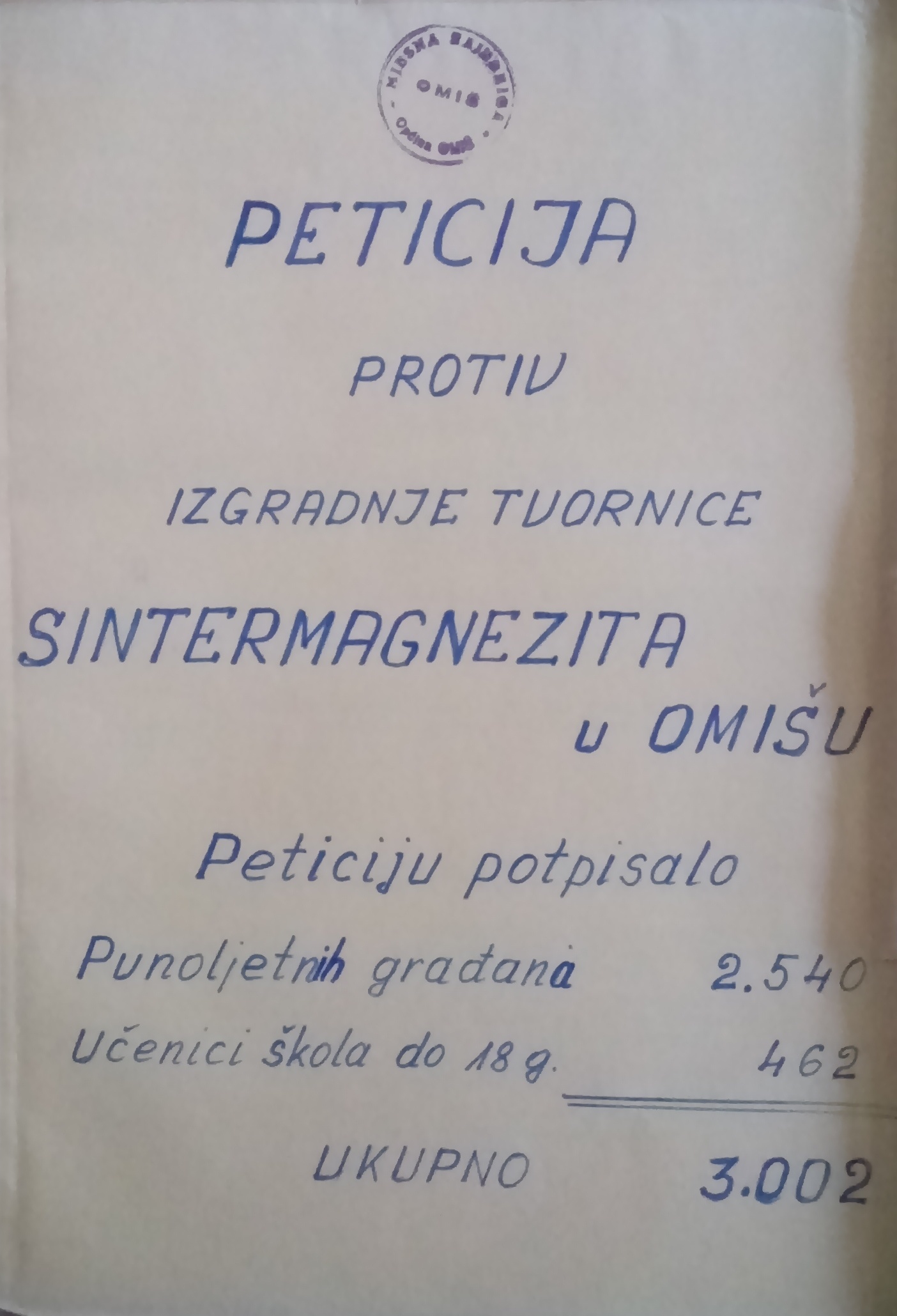

A petition drive was organised in Omiš on the next day, on 7 April 1979. It was signed by 3,002 persons: 2,540 eligible voters and 462 students under 18 years of age. By comparison, it should be mentioned that based on the population census, in 1971 the narrower Omiš area had 3,731 inhabitants, and in 1981 it had 4,800 inhabitants. The conclusions from the town meeting and the petition with copies of all 3,002 signatures were sent to the Omiš Municipal Assembly and to a range of republic-level institutions, including the Parliament of the Socialist Republic of Croatia, formally the highest constitutional state and governing institution in Croatia. According to the file cover, Parliament received the petition on 12 April 1979, and placed it ad acta ten days later, on 24 April. The petition was also sent to the participants of Second Conference on Adriatic Protection, held at the time on the island of Hvar, which resulted in further discussion on that subject among the professional and general public. Throughout the summer, referendums were organised decisions against construction of the sintered magnesia factory and pilot installation were adopted with considerable popular support in Omiš and the surrounding settlements. An example is the decision submitted to the Parliament of the Socialist Republic of Croatia on 3 August 1979 by the local community of Duće (a settlement near Omiš, along the Omiš-Split road). According to information in that decision, 539 of 665 eligible voters, or 81.05%, participated in the referendum in Duće . Out of that number, 532 voters, i.e. 98.70% declared that they opposed construction of the factory.

The press covered this subject and the activities of the local population in Omiš extensively. Articles written by Vesna Kusin in the daily newspaper Vjesnik during that and subsequent years are particularly noteworthy. In an interview in the newsmagazine Globus in 2015, she recalled that at that time she “consistently travelled to Omiš, where the demonstrations occurred, and wrote a plethora of articles on this matter, and ultimately the plant wasn't builtˮ (Museums of Hrvatsko Zagorje, Media report 08.04.2015).

Along with demands for environmental protection, the public statements from the local population and newspaper articles also contained criticism of local and republic institutions, as well as the investor, Dalmacijacement, because of they “went behind [the people’s] back,ˮ i.e. bypassed “the principle of self-governmentˮ and the opinion of the local community in the decision-making process. Responding several years later (1984) in Vjesnik to one negative article about the referendum held in 1979, a few residents of Omiš who took part in it said that “they are proud, especially because that referendum was the true expression of popular will against considerable pressure and manipulation from various social and economic structures.ˮ

As already noted, the sintered magnesia factory was not built, production of cement in the industrial plant at Ravnice was brought to an end in 1983, and in 2006 that location was transformed for tourism activities (Žižić and Marasović 2014, p. 47).

All documents are available for use and copying.