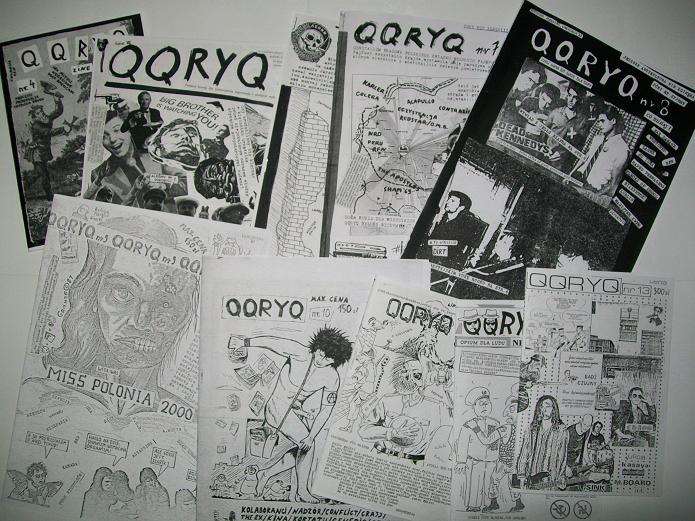

The beginnings of the collection of Piotr ‘Pietia’ Wierzbicki were related to the launch of ‘QQRYQ’ fanzine in 1985. Although the publication of the first two issues of the zine had been unsuccessful, after the third one ‘QQRYQ’ became a popular punk magazine in Poland. As an editor and publisher of the zine, Wierzbicki has built a broad network of contributors, correspondents, distributors, and readers both from Poland and from abroad. The readers of the fanzines came mostly from the middle class, but in the late 1980s, the punk movement was strong also among young proletarians. According to the popular song 'My punki' ('We, the punks') by the Vavel Underground band, there were a lot of the punks from the housebuilding vocational school ('punki z budowlanki'). But zines like 'QQRYQ' were to some extent exclusive and addressed mainly to the punk pupils and students with some "intellectual" interest in the movement.

The fanzines were sent via post, as well as sold on concerts. A social institution of buying and selling the fanzines, cassettes, and records was called "czadgiełda" or "giełda czadowa", the expression that means "hardcore market" or "hardcore exchange". Due to lots of contacts, which Wierzbicki had directly and correspondently, he could gather a substantial archive of music fanzines and other papers present in the third circuit, mostly anarchist ones. He collected also some printing matrices and many cassettes with hardcore punk music.

After the transition toward liberal democracy, Wierzbicki established an enterprise based on the ‘QQRYQ’ for a legal continuation of issuing the fanzine and cassettes. The business was named QQRYQ Productions and through the 1990s released almost one hundred cassettes, mainly with hardcore punk and reggae genres, so there are many fanzines, cassettes, and CDs from that decade in the collection. However, in 1999 Wierzbicki had to cease the enterprise because of sharp competition on the Polish music market.

The collection has never been institutionalized nor officially accessible for the public. It is seldom shown to the audience; last time zines from Wierzbicki's collection were shown as a part of the exhibition "Warsaw Punk Pact" in Leipzig in May 2017. The collection is still a private property of Wierzbicki and is held in his flat in Warsaw. Nonetheless, nearly every issue of ‘QQRYQ’ fanzine is nowadays digitally available on the zinelibrary.pl, a website dedicated to the documentation of the third circuit press in Polish People’s Republic.

In 1985, a few years after the first punk wave in Polish People’s Republic, the popularity of new hardcore style was rising. One of the most famous bands of that style was Dezerter, founded as SS-21 in May 1981 and renamed as Dezerter in September 1982. Piotr ‘Pietia’ Wierzbicki had been a friend of the group and had got inspired by Dezerter’s fanzine ‘Azotox’ before he launched his own punk magazine. Indeed, Zbigniew Matera, the brother of the Dezerter’s guitar player Robert Matera, was the closest friend of Wierzbicki and a member of ‘QQRYQ’ staff. Due to the friendship with Dezerter and other connections on Warsaw punk scene, it was quite easy for Wierzbicki to get in touch with punk bands and fan crews. Then he got contacts with punk in other Polish cities and abroad, mostly in the Western Europe and USA, but also in GDR and other socialist countries.

The punk scene in Poland was a predominantly underground phenomenon with strong anarchist and anti-communist inclination. But punk musicians, fanzines’ editors, and concerts’ audience were far from political engagement in ‘Solidarity’ union or any other oppositional group. They were more interested in constructing the autonomy of their own underground community and the communicational circuit than in official politics and ‘serious’ social conflicts. They put their energy in building durable connections among local scenes in cities of Poland and abroad, what they perceived as a way to achieve their collective independence as punks. The problem of the scene was, for example, lack of professional musical instruments and equipment. Another question was the music industry, reluctant to publish punk albums or give accreditations to punk musicians.

Moreover, the fanzines like ‘Azotox’ and ‘QQRYQ’ were issued in hundred or two hundred copies, so their publishers usually did not have troubles with censorship. Publishing low print number (not more than 100 copies) was free from the censorship, regardless of the subject of the issue. The higher number had to go to the censorship before the publication but secret police usually did not bother to seek for the editors of the fanzines.

On the other hand, the underground alternative scene was divided because of different aspirations of its members. Some groups aspired to perform publicly on official festivals and put their songs on radio charts, while others cultivated the DIY attitude and strictly obeyed the anti-commercial rules. Another problem emerged in the late 1980s, with the hostility and aggression of skinheads toward punks. In the first years of the 1980s, the skinheads and punks stayed colleagues; they represented different styles in clothing but had the similar taste in music. When after a few years, skinheads had turned to neo-fascist ideology, while punks had become openly libertarian or anarchistic, many fights or even street clashes between skinheads and punks began, with the most renowned in Nowa Huta.