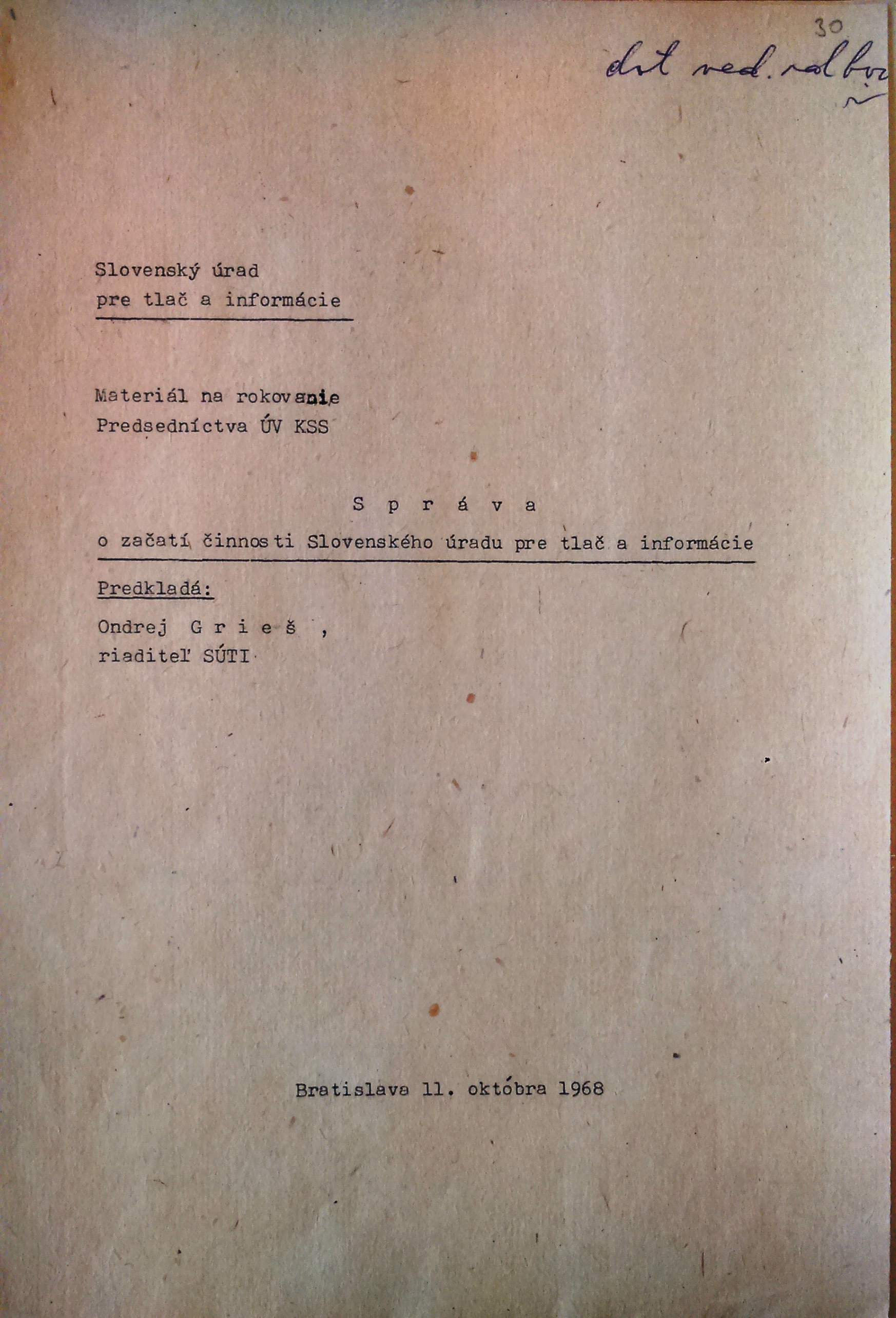

The origins of the Slovak Office for Press and Information (Slovenský úrad pre tlač a informácie, SÚTI) fund/collection go back to August 1968, when, as one of the first acknowledgments of “normalization” precautions, SÚTI was established. Its leading task was to regain total control over Czechoslovak official mass media which during the liberalising atmosphere of the Prague Spring, experienced an unexpected degree of freedom of speech, and a release from censorship and Party guidance. The Soviet Union, with Leonid Brezhnev in charge, looked at the situation in Czechoslovakia with resentment from the beginning. However, it was able to enforce its will only after the intervention of military forces of the Warsaw Pact in August 1968. SÚTI functioned as a state censorship and propaganda bureau. In the registers of SÚTI, reports and assessments of the stories published in the press, in radio broadcasts or on TV were collected. The primary aim of the systematic production of critical reports was to constantly regulate and eliminate all forms of “ideological impurity.” Along with these assessments, a system of sanctions against publishers or individual journalists was also installed (and could lead, for example, to a loss of registration), which was executed by the Department of Party Affairs in Mass Media (Oddelenie straníckej práce v informačných prostriedkoch) of the Central Committee of the Czechoslovak Communist Party. After the government decision had been issued on 4 September 1968, two institutions were established – the Czech and Slovak Offices for Press and Information (ČÚTI and SÚTI), coordinated by a federal board.

The process of producing assessements is well illustrated by an extract from the external reports. In 1969 the magazine Matičné čítanie was accused of being too “nationally-oriented”. This characteristic could be allegedly ascribed to every article. According to the author of the report, this could be seen as evidence of an “obvious anti-soviet stance.” The official party daily Pravda also came under scrutiny: the January 1969 issue contained an article that was criticised for similar reasons. The article was written by an employee of the Ľudovít Štúr Institute of Linguistics and depicted the period of the first Slovak state (1939–1945) as beneficial for the development of the Slovak language. According to the author of the critical assessment, the era after the Soviet liberation was then perceived as having a negative impact on the Slovak language, which cast a bad light on the Soviet regime. Other notable assessments include those in which authors accused the media of being too eager to commemorate Jan Palach’s death, such stories were published without an accompanying “critical commentary,” which was particularly desirable in those times. In February 1969, Pravda released an article about an Italian student who set himself on fire as a symbol of solidarity with Palach and in protest against the situation in Czechoslovakia. According to the author of the report, “it only repeats already published news about the attempted suicide of a 58-year-old worker, though this incident was not politically motivated.” The primary goal of producing such assessments was to blur the “delicate” facts, those which might have distorted an image of the normalization rhetoric, and subsequently to disqualify the “guilty” journalists. Nowadays, the collection of assessments and journalistic analyses in the SÚTI fund is freely accessible in the Slovak National Archive.