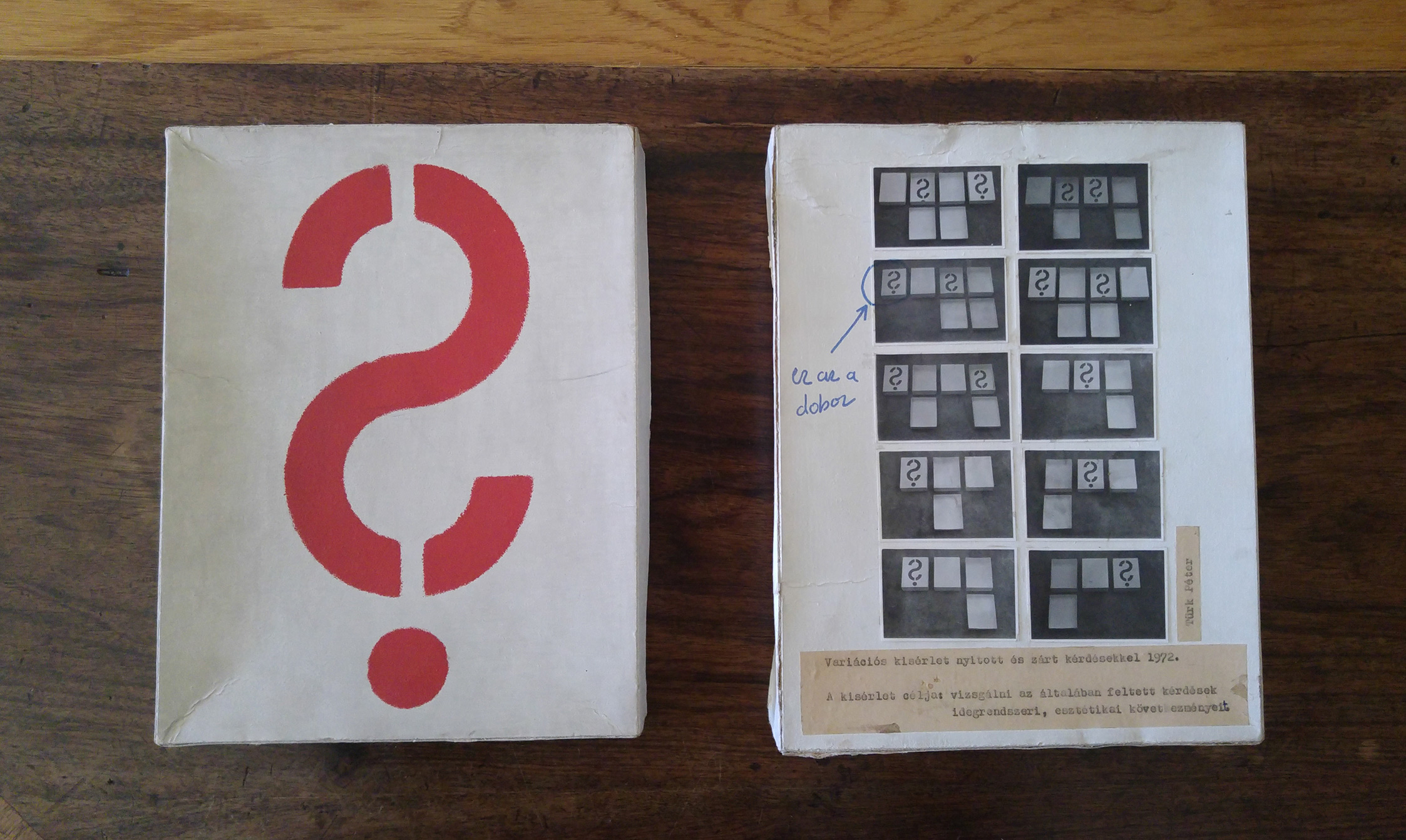

Cardboard box with a large, red, stenciled, symmetrical question mark on the outer top of one side and the inner bottom of the other side. On the outer back side, a series of ten photos arranged in a grid demonstrating the possible combinations of similar boxes in an open and closed state.

On the third photo the box on the left is marked with an arrow pointing to a handwritten caption reading “that is this box.” Under the photo appears the typewritten title of the work and the following sentence: “The aim of the experiment is to examine the sensory and esthetic effects of generally asked questions.” Beside the photos, above the label the typewritten name of the author is visible.

The handwritten commentary suggests that a box can be interpreted alone as well (this concrete example incorporates two differently positioned, painted question marks). Looking at the photos, one can conclude that more—though not necessarily identical—copies exist, which were given away (as this example got to the archive).

Politics did not constitute the primary context of Péter Türk’s oeuvre, but a subtle, sometimes ironic, criticism of the system can be observed in his works produced during the first half of the 1970s. During this period, he created geometric, but more and more conceptually oriented works, pursuing visual, semantic-logical investigations, which formed an implicit statement in the eyes of cultural politics at the time.

The question marks appearing in several series of his works are “visual conundrums,” which come into play via their color, position, material, constellation and, last but not least, their variations. Contemplating the object, the viewer becomes involved in a conceptual-associative process.

During our visit, we first wanted to define what is a generally asked question. According to professor Beke, “how are you?” or rather “what’s up?” is a good example. Hearing (or reading) a question of this type it is worth noting that this still concerns the sensory effect.

The object bears the marks of time and the consequences of its storage conditions. Dedicated wood crates or humidity control could not be provided for an item kept in a private archive, but it did not lose any of its authenticity and conceptual clarity even in its current condition.