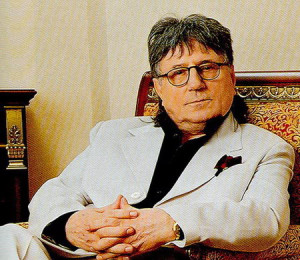

Mihai Dolgan (b. 14 March 1942, Vladimirești / Vladimireuca, Sângerei district – d. 16 March 2008, Chișinău) was a prominent Moldavian composer and singer, who became famous as the founder and uncontested leader of the musical band Noroc in 1966. Dolgan’s family was deported to the Buriat ASSR in 1949, as part of the wave of massive deportations affecting the MSSR during the late 1940s and early 1950s. After his family returned to Soviet Moldavia in 1956, Dolgan worked as an accordionist in his native Sângerei (1958–1959). In the late 1950s, he enrolled in the Ștefan Neaga Musical College in Chișinău (1959–1962). Although he was not allowed to study the accordion due to the lack of this specialisation at the college, he became one of the most accomplished accordionists in Soviet Moldavia, being part of several groups organised under the aegis of the Chișinău Philharmonic Orchestra (1964–1967). With the crucial support of the Philharmonic’s director, Alexandru Fedco, in 1966 Dolgan was allowed to form his own band, which was meant to perform “Moldavian songs with a modern rhythm” (as the Soviet press of the era phrased it). In fact, Dolgan’s initial idea was to create a jazz band, following his earlier experience as a jazz performer during his service in the Soviet Army, when he had been a member of the military orchestra in Kiev (1962–1964). However, under the influence of his colleagues and fellow Noroc members Valentin Goga and Alexandru Cazacu, Dolgan gradually understood the public’s demand for contemporary “commercial” music. Noroc thus came under the sway of British and American beat and rock music, notably The Beatles. Dolgan’s band pursued a “double strategy” during its performances within and outside the MSSR. While in Soviet Moldavia the singers had to abide by strict censorship rules and a pre-approved official programme, during their shows in other Soviet cities they deviated significantly from this model, peppering their performances with fashionable Western hits and their own songs. This strategy ultimately backfired in the summer of 1970, during Noroc’s tour of Ukraine, when the Party authorities in Odessa and Vinnitsa were appalled by the violent incidents at their concerts and by the “unacceptable” contents and stage behaviour of the band. Noroc was dissolved by a special order of the Minister of Culture on 16 September 1970. After Noroc’s banning in the MSSR, Dolgan worked in various philharmonic orchestras in Russia and Ukraine (notably Tambov and Cherkassy, 1971–1974). In 1974, he was allowed to return to Chișinău and to form another musical group, called Contemporanul (The Contemporary), this time under closer supervision by the authorities. Although the new band included many of the original Noroc members (notably, the brothers Alexandru and Anatol Cazacu and Ștefan Petrache), it never reached the heights of popularity achieved by its predecessor. Dolgan continued to enjoy a high reputation in musical circles throughout the 1970s and 1980s, while Contemporanul helped launch a number of prominent Moldovan artists, some of them still active. However, he was never entirely “rehabilitated” in the eyes of the communist regime, receiving public recognition only during the Perestroika period, when he was made a People’s Artist of the Moldavian SSR (1988). In the late 1980s, Dolgan and his colleagues were also active in the national movement. In 1987, they launched one of the first patriotic songs with a clear pro-Romanian message – Basarabia (lyrics by Dumitru Matcovschi, music by Mihai Dolgan). Although Dolgan collaborated, during his musical career, with a number of politically conscious poets and song writers (e.g., Andrei Strâmbeanu and Efim Krimerman), he rarely expressed an openly anti-Soviet stance. However, as he noted in a later interview, music was for him an unmistakable form of protest: “How can one play The Beatles and be a communist at the same time?” Dolgan’s music was emblematic for the tendency of the “last Soviet generation” to live outside of official constraints and norms. He remained famous as the author of such hits as: De ce plâng ghitarele? (Why the Guitars Cry), Dor, dorule (O, Longing), Cântă un artist (An Artist is Singing), Primăvara (Spring), etc. In the 1990s, Dolgan became less visible as a public figure, struggling to keep afloat the revamped Noroc project (Contemporanul had reverted to the old name in 1985), but with little success. In 2001, he was decorated with the highest Moldovan state distinction, the Order of the Republic, for his entire musical career. Two years after his death, in 2010, a commemorative plaque was installed on his apartment building in central Chișinău (executed by the sculptor Valerian Doicov). Mihai Dolgan remains one of the most original Moldavian musicians of the last fifty years, symbolising the creative synthesis of local musical traditions and Western-style modernity.