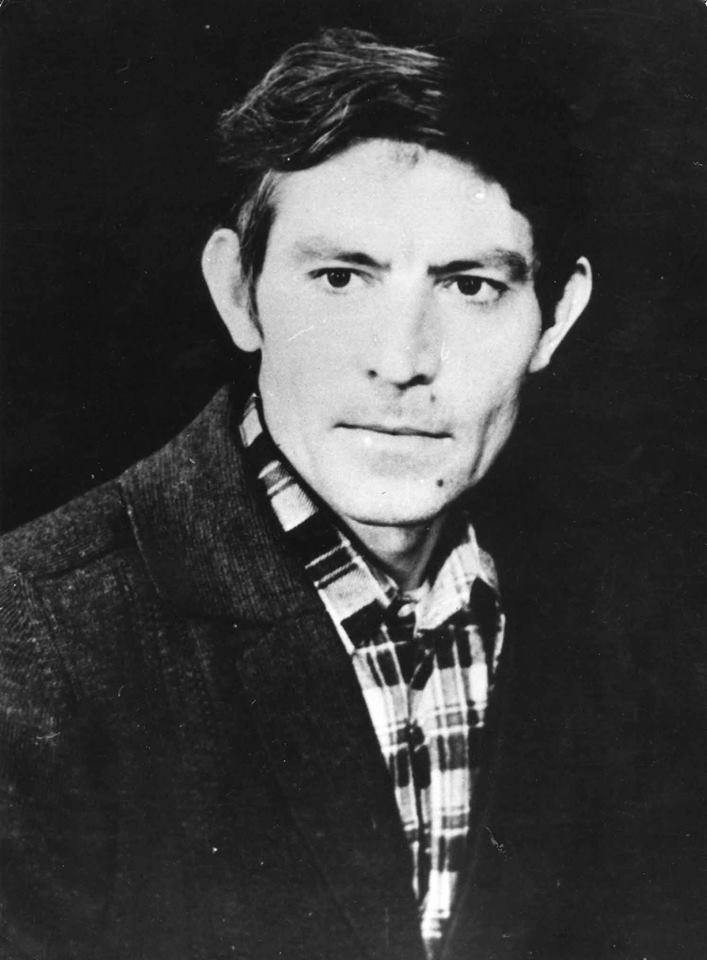

Vasyl Stus was born in the village of Rakhnivka, in the Haisynskyi district of the Vinnitsa region in Ukraine in 1938, moving with his family to Stalino (now Donetsk) the following year. Stus spent his formative years in Donetsk, later studying history and philology at Donetsk State University and teaching Ukrainian in the village of Tauzhne in Kirovograd oblast in 1959, before two years of service in the army. When he returned, Stus taught Ukrainian at a school in Makeevka in Donetsk oblast. In 1963, he matriculated to the Institute of Literature named after Taras Shevchenko in Kyiv, which was an important turning point in his personal history. There he became involved in the literary scene and the sixtiers movement, turning a quiet poet into a political figure.

Along with Viacheslav Chornovil and Ivan Dziuba, Stus spoke out against arbitrary arrests of artists, writers and human rights activists, which had taken place as part of the post-Khrushchev crackdown on the intelligentsia in 1964-1965. They used as their platform the Kyiv screening of Sergei Parajanov’s internationally acclaimed film “Shadow of Forgotten Ancestors,” based on a novel written by Ukrainian writer Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky. Dziuba spoke first, denouncing the arrests, but the KGB did not let him finish speaking. They chased him off the stage and switched on sirens to drown out his voice. According to Nadia Svitlychna, who was also in attendance, Stus stood up and shouted: "All those against tyranny, rise!" Only a few people out of several hundred stood up and they paid dearly for doing so. The philologist Yuriy Badzio and the literary critic Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska both lost their party memberships. Badzio was fired from his job and then in 1979 imprisoned for his work "The Right to Live," while Kotsiubynska's career as a gifted literary specialist and translator was over. In her recollections, Kotsiubynska remembered this episode vividly, noting that when Stus sat down, he was shaking, making Kotsiubynska wonder how a gentle soul like this would make it in such a harsh world. Indeed what sets Stus apart from so many others was the source of his intellectual resistance to the Soviet regime. It seemed to well up from a deeply principled core, which despite his gentle nature was the source of incredible intransigence in the face of myriad indignities forced upon Soviet citizens.

For his participation in this protest, Stus was kicked out of the Institute of Literature in Kyiv, after which he tried to have his poetry published through official channels to no avail. His volume "Kruhovert" ("Maelstrom") was rejected by Soviet censors, as was “Zymovi dereva" (“Winter trees”), despite generally positive reviews from his colleagues, the poet Ivan Drach and the literary critic Yevhen Adelheim. Both these volumes were published unofficially and circulated through underground networks. The publication of "Zymovi Dereva" in Brussels in 1970 was one of the charges levied against Stus during his trial, which took place in January-September 1972. During the trial, Stus was imprisoned in a cell at KGB headquarters on Volodymyrska St. in Kyiv, where he wrote "Chas Tvorchosti" ("Time of Creativity"). Total isolation fueled Stus's creativity rather than stymieing it, one of many reasons he proved so difficult to break.

Stus was sentenced to 5 years of hard labor and three years of exile, which he spent in Mordovia and the Matrosov settlement in Magadan oblast. His sentence ended in 1979, after which Stus returned to Kyiv and immediately took to defending members of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group who had fallen under scrutiny. In May 1980, he was arrested again and given another 10 years of hard labor and 5 years of exile, which he served in Perm-36, a forced labor camp for political prisoners. He staged hunger strikes to protest his treatment in the camp, but managed to write and smuggle out a number of poems.

In an interview with several members of the Kharkiv Human Rights Group (KHPG) in 1999, Armenian political prisoner Paruyr Haykiryan, who also served two sentences in Perm, recalled that neither Chornovil nor Stus behaved as though they were prisoners in a concentration camp. They lived for the sake of literature, art, and Ukrainian history. Hayrikyan said that Stus’ Ukrainian comrades deliberately shielded him from the banal language of Soviet protest, at times insisting that he not sign petitions, so that his poetry could speak for itself.

The Stus he describes is someone who maintained his humanity, never resorting to violence even when attacked by other prisoners. When his manuscripts were confiscated Hayrikyan helped organize a hunger strike demanding that Stus’ papers be returned to him. The camp administrators returned the nearly 100 manuscripts taken from Stus, indicating that indicates that they were trying to prevent Stus’ private principled rebellion from spreading to other inmates. Even so, his last collection of poems "Ptakh Duzhi" (close to 300 poems) was destroyed in Kuchino.

As powerful a force as Stus was in unofficial circles, among Soviet internal exiles comingling in hard labour camps and in émigré communities, he was not that well known in his own country until the late 1980s, when the policies of glasnost and perestroika lifted the veil on the suppressed recent past. In an interview with Mykhailyna Kotsiubynska, Yevhen Zakharov, director of KHPG, said the first time he had heard of Stus was in 1988, when he managed to get his hands on a volume published outside the Soviet Union. Zakharov was floored by how much Stus’ poetry pushed past what was imaginable in Soviet Ukraine.

On August 28, 1985, Stus was once again thrown into solitary confinement, because whilst reading a book he leaned his elbow on the bars in his room, which was a violation of the prison code. In response, he staged another hunger strike, which he vowed to keep to the end. He died during the night on September 4, under suspicious circumstances. Stus was buried in Perm before being repatriated to Ukraine in 1989, he now lies in repose at the Baikovo cemetery in Kyiv.