A leading Romanian intellectual of Jewish origin, Nicolae Steinhardt (1912–1989) came to be known mostly for his “literary testament,” an autobiographical volume which focuses on his conversion to the Christian Orthodox faith while imprisoned under communism. Published after 1989 as Jurnalul fericirii (Diary of blissfulness), this book epitomises the idea of “resistance through culture,” a post-1989 definition of the pre-1989 mainstream intellectual reaction to the system of values imposed by the communist regime in Romania (C. Petrescu 2008). Steinhardt was a member of the so-called generation of 1927, which comprised the most prominent intellectuals of the interwar period. Although he held a doctoral degree in legal studies, he nonetheless dedicated himself to cultural activities. As a Jew, he suffered from the wave of anti-Semitic persecutions perpetrated by the extreme right Iron Guard party and the military dictatorship of Marshal Ion Antonescu. Consequently, he lost his job as editor of the state-sponsored Revista Fundațiilor Regale in 1940. Under the communist regime, Steinhardt was a political prisoner for five years following a trial which the communist authorities staged against a group of prominent intellectuals from his generation during the wave of repression unleashed in the aftermath of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

It was not because he really belonged to an opposition group that Steinhardt was imprisoned; the accused in this trial were an informal group of highly educated and cosmopolitan intellectuals, who were transformed in the vision of the Securitate into an alleged “hostile group.” Taking his Jewish origin into consideration, the secret police summoned him to testify against his Romanian friends and fellow intellectuals, for the intention of the secret police was to incriminate them as “mystic and legionary [i.e., fascist] intellectuals.” Because he refused, the Securitate put him alongside the others and set up a trial against the entire group, which later came to be known as the Noica–Pillat trial, after the names of two leading personalities in the group. Due to the prestige and number of those involved, this event was the most notorious persecution perpetrated under communism against non-political intellectuals (Tănase 1997). Sentenced to thirteen years of imprisonment, Steinhardt went through the worst prisons in communist Romania, such as Jilava, Aiud, and Gherla.

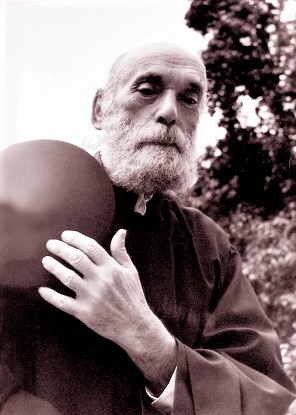

A secularised Jew, Steinhardt converted to Christianity in 1960 in the Jilava prison, following an ad-hoc religious service performed by several of his inmates who were clergy of various Christian denominations, including Roman Catholic, Greek Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox. It is worth emphasising the striking similarity between Steinhardt’s baptism and the widely known conversion to Catholicism of a Polish intellectual of Jewish origin, Aleksander Wat, while in a Soviet prison (Wat 1988). Steinhardt was released before completing his sentence, with the general amnesty of political prisoners in 1964. He resumed his literary activities as journalist and translator, managed to publish several books, and re-established himself as a reputed intellectual. A turning point in Steinhardt’s life occurred in 1980, when he became an Orthodox monk at the secluded monastery of Rohia in the northern region of Maramureș. Even there, he was continuously kept under surveillance by the Securitate. However, he dedicated himself to the writing of his secret memoirs, which he considered his literary testament. In spite of the constant surveillance, Steinhardt managed to transmit his extraordinary life experience, in particular that of his imprisonment and conversion to Christianity, through the manuscript entitled Jurnalul fericirii (Diary of blissfulness). He stubbornly rewrote the manuscript each time the secret police confiscated the version he was working on. He even managed to send some copies abroad to RFE, which broadcast them back to Romania. His funeral in March 1989, which was attended by some of the most prominent intellectuals in Romania, was also monitored by Securitate employees.

Nicolae Steinhardt was not involved directly in the making of any collection, but he is the author of one featured item from the Confiscated Manuscripts at CNSAS Collection, which seems to be a condensed version of his Jurnalul fericirii. This non-ad-hoc collection founded by the Securitate includes today only a copy, for the original was returned to his heirs in 2002, in accordance with the 2001 decision of the then Collegium of CNSAS to return confiscated materials upon request. Besides this abridged version of his memoirs and that which reached RFE, at least two other versions survived communism to be published. Before his death, Steinhardt was able to pass a version to a friend and to hide another in the monastery. Steinhardt’s memoirs became extremely influential during the time of ideological decay in the late 1980s for three reasons: (1) the author spoke about the solace of religion and proposed a different vision of the world than that based on the atheist communist system of values; (2) some versions of the manuscript, which was intended to be Steinhardt’s intellectual testament, circulated as a kind of samizdat in the intellectual circles close to the author; (3) the message of the memoirs was widely spread among Romanians via RFE. Thus, Jurnalul fericirii became after 1989 not only a bestseller, but also the epitome of what Romanian intellectuals name “resistance through culture” and claim – rightfully or not – to have been the only possible reaction against the Ceaușescu regime, which the powerful and ubiquitous Securitate defended until 1989 (C. Petrescu 2008).