Andrei Partoş (born 1949) is a journalist and musical commentator who practically founded Radio Vacanţa-Costineşti. Born in Braşov, Partoş graduated in psychology from the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Bucharest and practised for ten years as a clinical psychologist. In 1985, he gave up this profession to dedicate himself entirely to musical and journalistic activities.

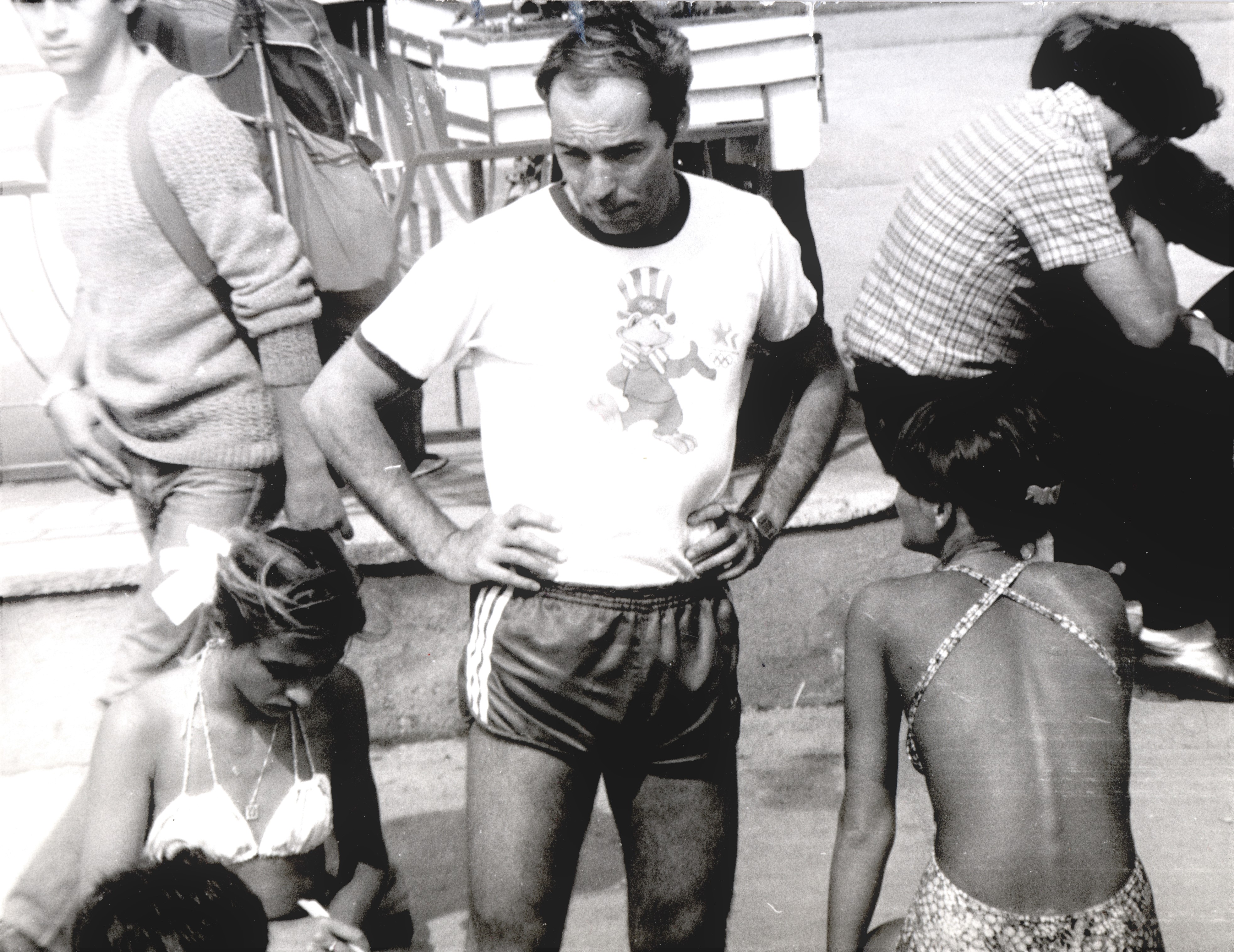

In 1979, the year in which he first set up Radio Vacanţa-Costineşti in a tiny doughnut shop, he made his first appearance on Romanian public radio, and he was soon invited to join its Youth division. After a pause of two years, he returned to Radio Vacanţa-Costineşti in 1982, and became the most representative face of the station, making an impression on a whole generation with his summer programmes through the 1980s. In the period 1985–1989, he was banned from national radio and TV.

Andrei Partoş is conscious that his activity at Radio Vacanţa-Costineşti before 1989 had a discreet but constant subversive character, which he describes in a nuanced manner: “I do not put what I did under the umbrella of a radical position. I was not an illegalist fighter. I was not a radical guy. But I was conscious that what I was doing there at Radio Vacanţa-Costineşti, together with my colleagues, was very different from what the official state culture offered. I knew, I was conscious that it was an alternative to the minus that young people got from public TV and public radio, and from public cultural institutions in general. And we were different; it was a distinct alternative.”

With regard to what he did consciously and subversively, Andrei Partoș comments: “above all I let the music speak instead of me.” As far as Romanian music was concerned, it was obtained through official channels: shops dealing specifically with music, the Electrecord record company, public radio, public TV. However, Romanian groups that were banned at the time were also played on Radio Vacanţa-Costineşti, and this was observed with displeasure by those charged with monitoring the radio station. “I would play Phoenix,” says Andrei Partoş, “although I wasn’t allowed to [they had been banned since they left for the West in 1976] – and I said I was playing Mircea Baniciu [the only member of the group who had not emigrated]. There was no proof cassette, but there were records and tapes there. Sometimes they came and scolded me for playing that sort of thing. They said they had ‘taken note’ – and they wanted to show that they were clever too. If they had wanted to make things very nasty, they could have done so – they would have found arguments for it. At the same time, what we had there was an outlet. A zone that functioned by a more permissive logic.” The group Phoenix was one of the most influential rock groups in pre-1989 Romania. It was first banned from radio and TV following the departure of Moni Bordeianu, one of the group members, to the USA in 1970. Then, the group reinvented itself, switching from being a Western-oriented rock group to becoming the main promoter of ethno-rock in Romania, which was apparently in tune with the cultural policy of the regime. They registered a huge success with this type of music, which was accompanied by verses inspired from pre-Christian folklore, and formulated in such a way as to imply double meanings. After their emigration and final interdiction, Phoenix reached a mythical status among Romanian rock groups, while their vinyl records were only sold on the black market.

When it comes to foreign music, however, the story of how it was acquired is itself an exemplary tale of Romanian communism. There were various methods, as Andrei Partoş recalls: “sometimes [it came] from the American Library: everything on the Top 100 Billboard. They would always give you the new songs that appeared in the charts. They wouldn’t give the tapes to just anyone – but they did give them to me. Generally I took them home, copied them, and took them back. The irony is that there was a Securitate investigation room just ten metres away. Then there was a trade in tapes copied by various guys that they used to call ‘mafiosos’ at the time because they didn’t know what the Mafia really was. I also had very good relations with some people who received music on vinyl records, and I copied those too. I should also mention the connection through people on aeroplanes and ships. Pilots, stewardesses, sailors – I gave them money and a list of what exactly I needed, and they would come with the music. In addition, around 1984, even the BTT (Biroul de Turism pentru Tineret – Youth Tourism Office) started to order music, through a contract with a company in Germany. They brought in singles, small vinyl discs, good ones. I was at a discotheque where you paid in hard currency, and when I was leaving, the boss there let me have several hundred singles.” At times this activity was not without its risks: “Those of us who bought foreign music, of course we were followed. But I had no problems with the people who were on the watch – because I wasn’t selling, just broadcasting. I was, so to speak, in the accepted zone.” Even some of the Securitate people asked for music from the West. It was said that one of those who gave approval, tacitly, to the large-scale broadcasting of foreign music was Nicu Ceauşescu, the eldest son of the presidential couple Elena and Nicolae Ceauşescu, who was practically a sort of unofficial “patron” of Radio Vacanța-Costinești. It is a fact that the acquisition of the latest-generation equipment that made the Vox Maris discotheque in Costineşti the most advanced and most sought-after discotheque in the summer season in Romania before 1989 was approved by the son of the then Romanian dictator.

Andrei Partoş was not a member of the Romanian Communist Party. “Seemingly my Hungarian and Jewish origins didn’t inspire sufficient trust, and I didn’t ask or want to be a member of the party anyway.” As regards his relations with various institutions of the communist regime, Andre Partoş adds: “I had a tense relationship with the Securitate. I always felt they were nearby, and sometimes I had dealings with them. In 1976, my sister emigrated to the USA – so I had an additional vulnerability. I don’t say of myself that I was a hero. Perhaps I was just a bit reckless, but no way a hero. I didn’t make crazy, radical gestures; I was a lucid, calculated, rational person. The music I played was my constant way of being subversive towards that regime. When I played ‘I want to break free’ [by Queen] at a discotheque or on Radio Vacanţa, everyone knew what we were referring to. And at the discotheque they sang along from the heart. Or on 23 August [the national day of Romania before 1989] I would put on ‘Paranoid’ by Black Sabbath. What more was there for me to say? There was no need to say any more.”

Andrei Partoş believes in the benefits of recovering the memory of problematic times, and pleads this cause: “It is important to know what it was like then – both for us and for the generation that will come after us, because otherwise the history of this country will not be understood. For example, there were lots of drastic restrictions – and perhaps those of us who experienced the Costineşti episode are in a position to appreciate freedom differently. And to talk about it as something very precious. Apart from that place, Costineşti, you had all sorts of restrictions – the problem with water, with light, with food. At Costineşti you forgot them, you were in another world. And the memory of that world has to be told.”

Currently, Andrei Partoş is the presenter of a well-known marathon programme on Romanian public radio. This, he says, is a natural continuation of what he did, in the summers of the 1980s, on Radio Vacanţa. He believed then and now he is convinced that “radio must be dialogue. Not talking on your own, but talking with people, for people.”