Tibor Philipp (1953–) was a member of the Inconnu group. He participated in and organized many oppositional events in the 1970 and 1980s. His originally worked as a pressman and, later, businessman.

He joined Inconnu in 1982. His friendship and family tie to György Krassó was very significant in the formation of of his mindset and his artistic and political activism. He lived in Krassó’s former flat in Nádor Street, which at the time was named Ferenc Münnich street (Münnich was a prominent Hungarian communist politician who served as the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the People’s Republic of Hungary from 1958 to 1961). The flat became a central, legendary site of the oppositional movement and of the performances of Inconnu, including the banned exhibition “A harcoló város/The Fighting City, 1986,” the works for which were destroyed. This flat was the main base of the hunger strike in 1988, which was organized as an oppositional gesture in response to the arbitrary revocation of passports. The apartment was also the seat of the Hungarian October Party, which was led by Krassó in 1988.

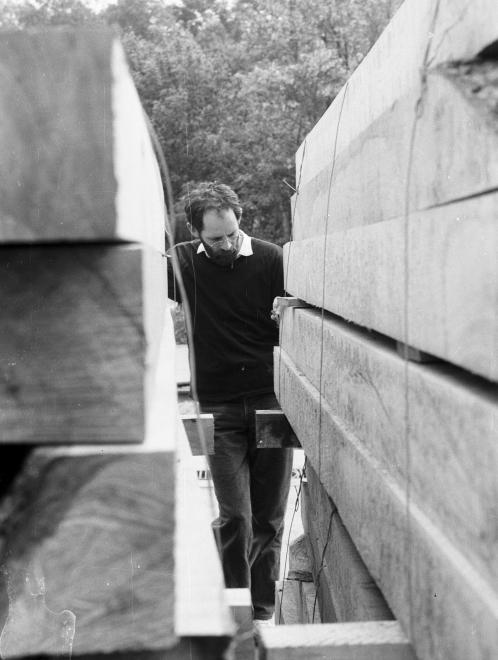

An investigation was launched by Department III of the Ministry of Home Affairs into his activities under the covername “Fraudster.” In addition to being kept under observation, Philipp was also prohibited from traveling to the West and faced difficulties finding employment and, therefore, earning an income. Members of the Inconnu group often had to accept jobs which had nothing to do with their professional qualifications. Philipp worked as a carpenter in Bálint Nagy’s illegal architecture company. Nagy had ties to the samizdat periodical Beszélő.

In an interview held in 2014, Philipp emphasized the central role of 1956 in his mindset. He criticized the commemorations of the revolution which were held in the 2010s because of the lack of genuine content. In his opinion, the way in which 1956 was remembered formed the fault line between artists like those who participated in these commemorations and the circle of Beszélő. The latter group approached the revolution in an ambivalent way. In contrast with these “elite-intellectuals,” the “plebeian” young people from rural areas followed the so-called “pesti srác,” or “Pest boys” attitude, in other words they glorified the image of young men in Pest taking up arms and fighting in the streets, heroically if also hopelessly, against the Soviet forces. The intellectuals wanted to implement reforms from within the system, while Philipp and his fellows wanted to change the system.

Philipp was a key figure because he not only organized but also diligently documented the events. He took photos of the actions and demonstrations held by democratic opposition groups, and he also took photos of György Krassó, for example when he changed the street sign for Ferenc Münnich street to Nádor street (the name which it bears today). His documents and records were given to collections, for example to Artpool and the

Open Society Archive. His photos are available on

Fortepan.