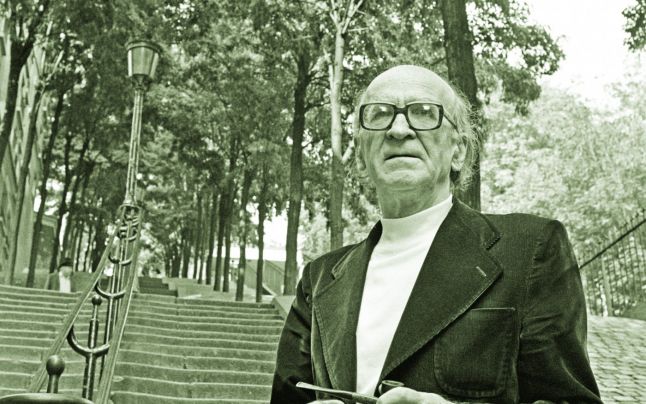

Mircea Eliade (born 28 February 1907, Bucharest, Romania - died 22 April 1986, Chicago, USA) was a Romanian historian of religions, philosopher, and writer who decided to prolong his activity in the West after 1945, where he became one of the most well-known Romanian intellectuals in exile. He was born into a middle-class family. From an early age, Eliade showed a remarkable literary talent, as well as an interest in science. His early debut took place in 1921 at the age of fourteen, with an article in a magazine for scientific popularisation. From 1926 to 1934, he published numerous articles on cultural themes in the daily newspaper Cuvântul, among those worth mentioning being “Itinerariu spiritual” (Spiritual itinerary), which appeared in several issues of the paper in 1927. The literary historian Zigu Ornea considered this text a “programme” for the young generation of intellectuals, through which Eliade prompted them to “unity and common goals” (Ornea 1995, 147). Intellectuals such as Petru Comarnescu, Constantin Noica, Emil Cioran, Mircea Vulcănescu, Sandu Tudor, and Mihail Polihroniade belonged to this generation. The young group came together in 1932–1934 under the aegis of Criterion, an association that organised cultural conferences on various themes. The adherence of some Criterion members to the Legion of the Archangel Michael led to the association’s dissolution (Ornea 1995, 150–151).

From 1925 to 1928, Eliade attended philosophy courses at the University of Bucharest, where he had the opportunity to meet Nae Ionescu, professor of logic and metaphysics, who had a strong influence not only on Eliade’s intellectual development, but on the entire group he belonged to. Nae Ionescu played an important part in the shaping of both his scholarly and political interests and ideas. Furthermore, between 1928 and 1938, Eliade was an assistant to Nae Ionescu at the University of Bucharest. Influenced by Nae Ionescu, but also by his reading of James George Frazer, Eliade decided to devote his career to the history of religions. In 1927, he travelled to Italy, where he met the Italian Indologist Giuseppe Tucci. Their meeting had a major influence in his decision to leave for India to study Sanskrit and Indian philosophy. As a beneficiary of a scholarship offered by the Maharaja of Kassimbazar, Eliade spent the years between 1928 and 1931 in India studying Indian philosophy with professor Surendranath Dasgupta at the University of Calcutta. Based on his research there, in 1936, he published Yoga. Essai sur les origines de la mystique indienne, a paper on the history of religions which put him on the map among Orientalists outside Romania. His personal experience in India inspired Maitreyi (1933 – published in English translation as Bengal Nights, 1994), the novel he would be acclaimed for in the Romanian literary world. Several other novels which appeared in Romania followed, i.e. Domnișoara Christina (Miss Christina, 1936) and Nuntă în cer (Marriage in Heaven, 1938).

During the second part of the 1930s, Eliade’s political thoughts and attitudes became radicalised. Like other intellectuals of his generation, Eliade adhered to the Legionary Movement. According to Florin Ţurcanu, one of Eliade’s biographers, his political radicalisation happened gradually from 1935 to 1937, with the intellectual influence of Nae Ionescu playing a major part (Ţurcanu 2006, 312–318). Between 1937 and 1938, Eliade wrote numerous articles in the Legionary press, some of them bearing virulent undertones of anti-Semitism, and even participated in the Iron Guard’s election campaign (Ţurcanu 2006, 347, 357–358).

In the aftermath of the Iron Guard’s rapid rise to power and its violent actions, King Carol II’s regime took repressive measures against the Legionary elite in 1938. In July 1938, Mircea Eliade was imprisoned for his political activity in an internment camp at Miercurea Ciuc, where he remained until October 1938. He was released through the intercession of some relatives. They also succeeded in getting him appointed as cultural attaché at the Romanian Embassy in London. Consequent to Romania’s entering the war on the side of the Axis and breaking its diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom, Eliade was moved to Lisbon, where he served as cultural attaché until his discharge in 1944.

Finding himself on Western European soil, Eliade had since 1943 decided not to go back to his homeland. In 1945 he moved to Paris, where the kernel of the Romanian cultural emigration was. The French capital was regarded by many Romanian intellectuals as a starting point for an international career. With the help of Georges Dumézil, Eliade managed to get access to the École Pratique des Hautes Études, where he taught the history of religions, although for a limited period of time. At the time of his arrival in Paris, French society was undergoing a purge of intellectuals who had sided with right-wing extremism. Eliade kept his Legionary past a secret for fear it might endanger his access to an academic career in the West (Laignel-Lavastine 2004, 470–471). The descent of the Iron Curtain enabled him to conceal his past, as Eliade’s pro-legionary publications were no longer available in the West. When details of it emerged, Eliade “deliberately chose to reinvent his past rather than face it” (Ţurcanu 2006, 603). According to Norman Manea, in his autobiographical writings Eliade missed a good chance openly to face his past and to own up to his mistakes (Manea 1992, 94). Trying to explain this attitude, Laignel-Lavastine compares Eliade to Heidegger and argues that Eliade “does not seem to have understood ‘the gravity of his error’” (Laignel-Lavastine 2004, 476).

During his time in France (1945–1956), Eliade published three books for which he was internationally recognised in the field of history of religions: Techniques du Yoga (1948), Traité d'histoire des religions (1949) and Le Mythe de l'Éternel Retour (1949). Thus, in 1956 he was invited to the USA by the Divinity School of the University of Chicago to give the esteemed Haskell Lectures and to be a visiting professor. He later accepted the offer to become a professor at this institution, and in the period 1957–1968, Eliade was the head of the Divinity School’s History of Religions department, where he also launched the academic journal History of Religions. There he made a fundamental contribution to consolidating the history of religions as an academic field in the USA. Subsequent to his moving to the US, several of his works were published in English: The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion (1959; initially published in German: Das Heilige und das Profane, 1957) and A History of Religious Ideas (three volumes: 1978, 1982, 1985, initially published in French).

At first, the Romanian communist regime banned Eliade’s work on account of his political involvement in the 1930s. In February 1960, a military court in communist Romania convicted a group of twenty-three intellectuals in the so-called Noica-Pillat political trial. One of the charges was the fact that two copies of Eliade’s Noaptea de sânziene (published in English translation as The Forbidden Forest, 1978) had been brought by actress Marietta Sadova from Paris and circulated clandestinely among her acquaintances (Tănase 2009a, 370–379). However, the attitude of the communist regime towards Eliade changed in the 1960s when the regime detached itself from Moscow and shifted towards national communism. As he was one of the most renowned Romanian intellectuals in exile, Eliade was regarded in an ambivalent manner by Ceauşescu’s regime, which was interested in reclaiming the part of Eliade’s work dedicated to the “Thraco-Dacian lineage”, which could legitimate it (Laignel-Lavastine 2004, 548). The greater part of his work, however, remained inaccessible to the Romanian public under communism. Eliade generally refrained from taking a critical stance towards the communist regime, apart from occasional gestures, such as taking part in the formation of a support group for exiled anti-communist General Rădescu in December 1947. Alexandra Laignel-Lavastine argues that Eliade or Cioran’s muted attitude towards the communist regime could be easily explained by fear of their pro-fascist past being revealed through press campaigns in the West initiated by the communist authorities (Laignel-Lavastine 2004, 547).