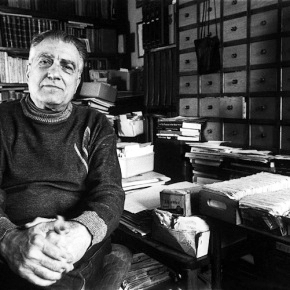

Adrian Marino was a Romanian literary historian and critic, who succeeded in gaining a notable international visibility, despite the fact – truly unique in communist Romania – that he had never worked for a state institution. Born in Iaşi on 5 September 1921 in a middle class family, Marino, at his parents’ initiative, attended a military high school, and experience he remembered as traumatizing because of his incapacity to adapt to the principles of military life. His early intellectual formation took place at the end of the 1930s and the mid 1940s, when he attended classes at the universities of Iaşi and Bucharest. His literary debut occurred in 1939, in Jurnalul literar (The Literary Magazine), when he was still a high school student. Professor and literary critic George Călinescu noticed him as a student, and Marino became his teaching assistant at the University of Bucharest in the period 1944–1947. George Călinescu’s option to support the new communist regime for opportunistic reasons, as well as Marino’s criticism of his professor’s vision – which dominated literary history and criticism in communist Romania – led to a separation from Călinescu and the end of his activity at the University of Bucharest in 1947. In 1945, Marino became a member of the youth organization of the National Peasants’ Party (PNŢ), one of the dominant parties in the inter-war Romanian political system. In the context of the repression by the communist regime of the so-called “historical parties,” Marino, along with other young members of PNŢ, tried to continue to publish illegally the party newspaper Dreptatea (Justice), and contributed to drafting certain ideological texts for PNŢ. Because of this youthful political activity he was arrested in 1949, and spent eight years in communist political prisons (1949–1957) and six years of house arrest in the Bărăgan (1957–1963).

In 1965, when political prisoners in Romania were gradually being freed and socially reintegrated, Marino was given the right to publish, and in 1969 he was legally rehabilitated. Consequently, he resumed his editorial activity in 1965 with the volume Viaţa lui Alexandru Macedonski (The life of Alexandru Macedonski). In an attempt to make up for his years of detention, he engaged in intense cultural activity in the period 1964–1989, both in Romania and abroad, publishing in 1980 his first book in France at Gallimard Publishing House under the title L'herméneutique de Mircea Eliade. In order to preserve his intellectual freedom, Marino carried out this intense activity outside the institutional framework of the communist state. In this respect, Marino confessed in his memoirs: “I have been since my release from prison (1963) a complete freelancer, with no ‘employment record,’ not listed on any ‘payroll,’ etc.” (Manuscript, 309; Marino 2010, 255). This special situation was made possible by the high royalties paid by the Romanian and foreign publishing houses. In addition, he carried out a vast correspondence with Romanian intellectuals in Romania and abroad, for example, Mircea Eliade, Emil Cioran, Constantin Noica, Matei Călinescu, and Mircea Carp. In recognition of his cultural activity, Marino received the Herder award in 1985.

After 1989 he asserted himself as an ideologist of the democratisation process in Romania and as a civic activist. In 1990, he founded in Cluj, together with dissident Doina Cornea, the Anti-totalitarian Democratic Front, and he was a founding member of the Association of Professional Writers of Romania, an alternative to the Writers’ Union of Romania, created during the communist regime. In 2010, five years after his death, his memoirs were published under the title Viaţa unui om singur (The life of a lonely man). The publication of these memoirs, which represent a well-structured and virulent attack against intellectual life in communist and post-communist Romania, generated heated debates in the Romanian cultural press.

The debates also covered the topic of opposition to Romanian intellectuals who collaborated with the regime, and raised the problem of Marino’s relationship with the former Securitate. These controversies were initiated by a series of articles published in one of the most important Romanian newspapers in the first half of 2010. The articles were based on information from a file of the Department of External Information (DIE), one of the Romanian secret services during the Ceauşescu period, which stated that Adrian Marino had been an informer and “influence agent” of the Securitate and subsequently of DIE in its actions concerning the Romanian immigration towards the West, in the period 1970–1980. The file in question contained no documents signed by Marino, only reports and notes of the secret service officers concerning Marino’s activity as an informer. These revelations divided Romanian public intellectuals into Marino’s accusers and his defenders. Among the former, Vladimir Tismăneanu stated his disappointment that such a very active public intellectual as Adrian Marino had collaborated in any way with the Securitate. Among the latter, Gabriel Andreescu, former dissident and civic activist, claimed that, in the absence of a signed pledge or of notes signed by Marino, Marino’s true relationship was with the Securitate cannot be evaluated with certainty (Andreescu 2012, 26-28). Marino himself admitted in his memoirs to having discussed and supplied information to certain secret police officers, without signing a pledge: “I only answered certain imperative questions. As many other political prisoners were forced to do. At least, I gave no written statements, as Corneliu Coposu and many others did. Above all, there was no official ‘pledge,’ written, signed, and dated. It was a very special relationship, specific for my category. I couldn’t refuse to answer one question or another. Only that the ‘answer’ had many possible nuances and interpretations; and, from my point of view and that of my interlocutors, it was without any real ‘political’ information, to which I had no access.” (Manuscript, 291; Marino 2010, 239). Given his notoriety, but also the nature of the documents preserved in the archives of the former Securitate, the Marino case represented one of the most significant controversies in post-communist Romania on the topic of the collaboration with the communist secret police. Beyond these debates, Marino’s memoirs remain a detailed confession and one of the most elaborated criticisms concerning the relationship between the intellectual and the authorities in communist Romania.