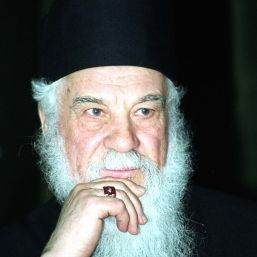

Gheorghe Calciu-Dumitreasa (1925–2006) was a Romanian Greek-Orthodox priest, an anti-communist dissident, and a fighter for human rights. He was born on 23 November 1925 in Mahmudia, Tulcea county, near the Danube Delta, in a large poor family; he was the only one of the eleven children who managed to go to school (Bourdeaux 2007). During his high school years, Calciu-Dumitreasa joined for two short periods of time Frăția de cruce (Blood Brotherhood), the youth organisation of the Romanian extreme right political party, the Iron Guard. Because of his political sympathies, he was put on trial, but he was acquitted by the Military Court of Constanța in 1942. After the end of World War II, Calciu-Dumitreasa again joined Frăția de cruce as a medical student in Bucharest. After the communist takeover in 1948, he was imprisoned and sentenced to eight years in prison because of his political allegiance to the Iron Guard. As he told The Washington Post in 1989, he was jailed because he and other like-minded friends protested against “atheism, the collectivisation of the means of production, and the destruction of the intelligentsia and the bourgeoisie”(Sullivan 2006).

In 1949, Calciu-Dumitreasa was sent to the Jilava penitentiary and then transferred to the prison in Pitești. At Pitești he participated in the infamous process of re-education that used permanent torture as the main instrument for transforming detainees into “new men.” In 1954, as the regime tried to distance itself from what happened in the Pitești prison, he was tried for his part in the re-education programme and received another sentence of fifteen years. He was released from prison in 1964 when the communist regime declared a general amnesty for all political prisoners (Deletant 1995, 39; Cătănuș 2007, 243). According to his own confession, tormented by the terrible sin of being one of the torturers at Pitești prison, Calciu-Dumitreasa found in Orthodox Christian faith a means of coming to terms with his painful past and thus decided to become a priest and distanced himself from his former political allegiances. Because on his release from prison he was forbidden from studying theology, he studied French. Then, with the consent of Patriarch Justinian of the Romanian Orthodox Church, he secretly completed his studies for the priesthood (Sullivan 2006). Ordained as a priest in 1973, he became a teacher of French and New Testament at the Orthodox Theological Seminary in Bucharest (Cătănuș 2007, 243).

Calciu-Dumitreasa’s dissident activities began in September 1977, when he deplored the demolition of churches in the centre of Bucharest, especially of the Enei church, the first such historical monument which was torn down after the earthquake of March 1977, on the grounds that it was too damaged to be consolidated. On 30 January 1978, he delivered a sermon in the Patriarchal Cathedral in Bucharest against atheism and labelled materialism as “a philosophy of despair.” One year after the earthquake of 4 March 1977, Calciu-Dumitreasa delivered another sermon to commemorate the death of the students who had died under ruins of the collapsed building of the seminary. His actions were severally sanctioned by his superiors who forbade him to preach in the Patriarchal Cathedral and questioned his decision to organise a service in memory of the seminary students (Cătănuș 2007, 244). Despite these early warnings, Calciu-Dumitreasa decided to hold a series of seven non-conformist sermons at the church of the seminary between 8 March and 19 April 1978. Targeting both seminary students and young people in general, the sermons dealt with sensitive issues for the communist regime and the Romanian Orthodox Church, such as atheist education, the relation between the state and the church, and the role of priests, who were supposed to take care of their parish communities and should thus oppose the demolition of the churches (Cătănuș 2007, 244).

The new patriarch, Justin Moisescu, considering that Father Calciu-Dumitreasa had betrayed the Church, expelled him from his teaching position at the Orthodox seminary. Harassed by the Romanian secret police, the Securitate, he endorsed in 1979 the initiative of a group of workers and intellectuals in the city of Drobeta-Turnu Severin to create the Free Trade Union of the Working People of Romania, and agreed to act as its spiritual leader. On 10 March 1979, he was arrested, put on trial, sentenced to ten years of imprisonment on the charge of “propagating fascist ideology,” and sent to the prison in Aiud. The charge was fabricated, as the communist regime tried to use his former political engagement with the Iron Guard to discredit him and justify his imprisonment. His arrest triggered a wave of international protests involving British, French, and Swiss members of parliament, members of the US Congress and international organisations such as Christian Solidarity International. Due to this international pressure, Calciu-Dumitreasa was released in 1984. As the renewal of Most Favoured Nation status for Romania by the US Congress was conditional on the observance of human rights, the authorities granted Calciu-Dumitreasa and his family exit visas in 1985 (Deletant 1995, 100, 231, 195). During his exile in the United States, he worked in construction as an unqualified worker to support himself and his family. Calciu-Dumitreasa did not abandon his fight against the communist regime and its atheism, as he continued to deliver radio sermons, to give interviews to foreign radio stations, including Radio Free Europe, to lead demonstrations, and to lobby the US Congress. All his actions were aimed at raising the awareness of international public opinion about the repressive nature of the Ceaușescu regime (Sullivan 2006; Cătănuș 2007, 246-260). From 1989 until his death in 2006 he ministered at the Holy Cross Church in Alexandria, Virginia. He is buried in Romania.