The distinctly unique group identity of the Hungarian veterans’ circle in Provence is visible in the fact that their members took an active part in both of the hottest armed conflicts of the Cold War: as teenage insurrectionists in 1956 Hungary, and a few years later as volunteers of the French Foreign Legion in the final phase of the devastating Algerian war. Due to much more powerful counter-forces, finally they lost both their fights; however, as the lucky survivors, they managed to win the peace. Thus today they are among the few witnesses who have been given the chance to recall those troubling events that took many of their generational fellows, who died young or disappeared worldwide some 60 years ago.

A conservative estimate of these youngest recruits of the Legion, a few of them still underage at that time, is 500 among well over of 3,000 Hungarian volunteers total, who, following 1956 served in Algeria under the French tricolor and the red-green banners of the Legion. As a result of five years of archival and oral history research both in Hungary and France, more than the half of them, 269 members of the younger age group, have been identified by name and personal data. Finally, some two dozen Hungarian veterans were found in Provence and Corsica, and nine of them volunteered to share their memories with the wider public as the main characters of a feature length documentary film and a 500-page documentary book. (See Béla Nóvé’s film and book of the same title and subject, Patria nostra, published in late 2016.)

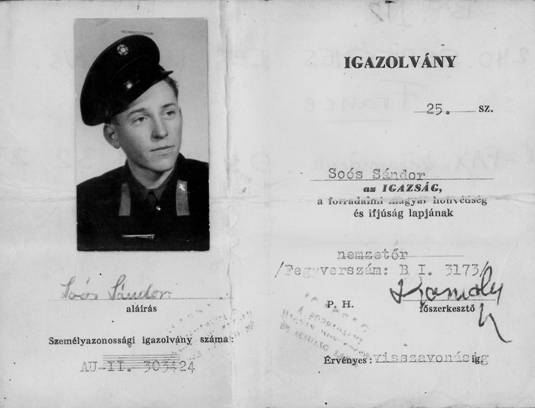

Even the first interviews and questionnaires of the veterans proved with shocking evidence how deeply and decisively their 1956 experience was etched in their memories. For various personal, biographical reasons, in the autumn of 1956 they all joined the protest demonstrations and the revolutionary unrest with great enthusiasm. Now nearing the age of 80, they still remember this time as their “baptism by fire.” The then thirteen-year-old János Spátay volunteered as a courier, passing secret messages sewed in a football from the isolated revolutionary troops across the bridges of Budapest that were blocked by Russian tanks. Fourteen-year-old Béla Huber from Sopron was the first to throw a hand grenade at the local headquarters of the ÁVH (the communist secret police); he continued to hide out in the woods along the Western border with other teenage boys for a month after the adult insurgents had all fled to Austria. Sixteen-year-old Gyula Sorbán took up arms on the first night at the siege of the Radio headquarters and for days was busy producing Molotov cocktails until he was gravely injured in the leg by a Russian tank grenade. Sándor Soós, a 17-year-old apprentice miner in Oroszlány protected the entrance of the New York Palace, a hotel and press center in downtown Budapest, with a light machine gun and only fled to the West with the last groups of insurgents one week after the second Soviet invasion.

He was the one, who, at the request of the researcher, described his 1956 memories in a twenty-page manuscript (the brief selection here is an excerpt), and then discussed his fighting experiences in detail on camera when visiting Budapest with László Eörsi, an expert of freedom fighter groups of 1956. His testimony was all the more appreciated by the historian Eörsi, since there are hardly any archival records left behind by the group that defended the New York Palace in Budapest.