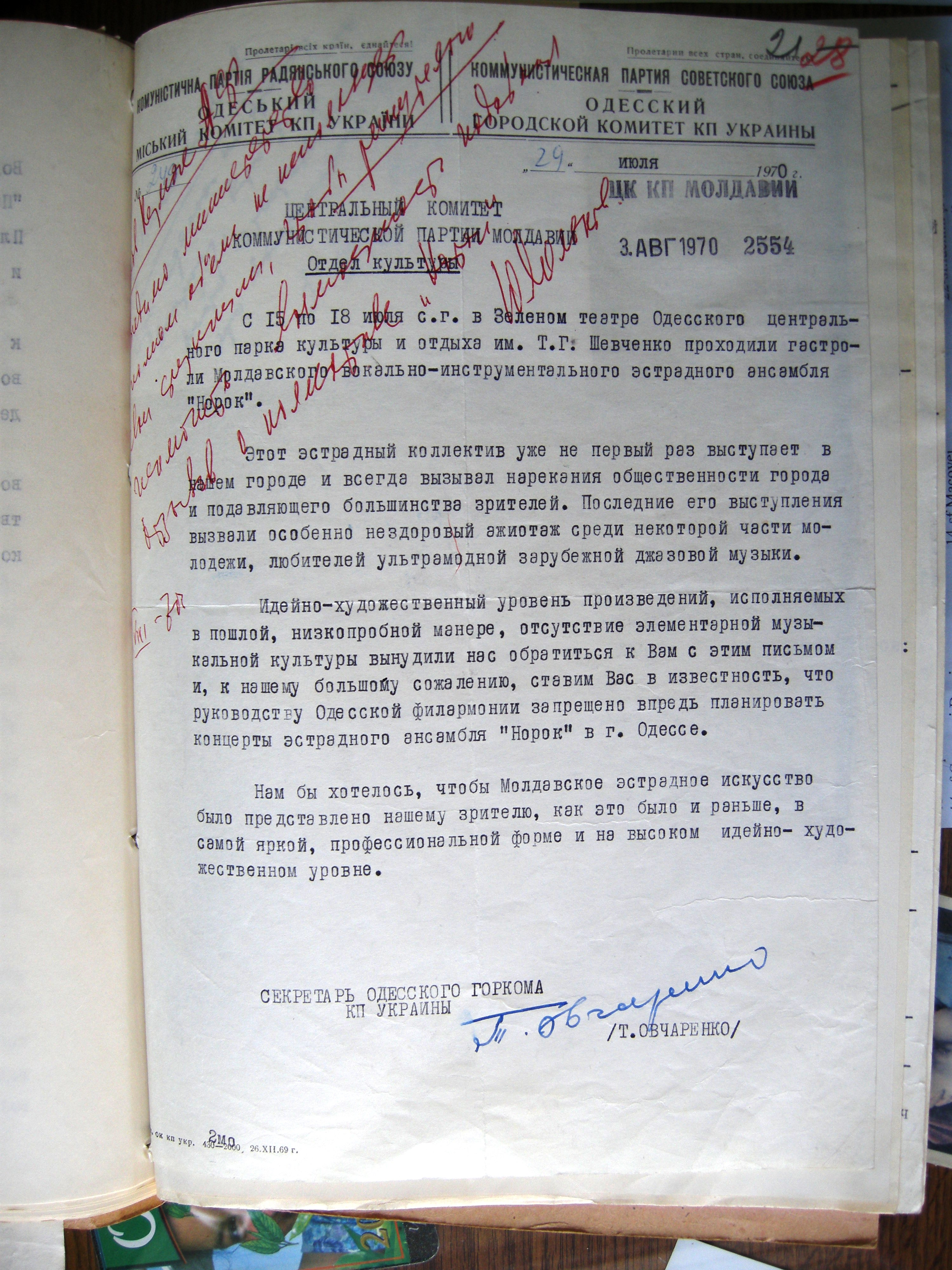

By the second half of 1970, Noroc had reached a wide and growing popularity. Its frequent tours throughout the entire Soviet Union were tolerated and encouraged by the local Moldavian leadership, including for financial reasons. However, the strategy of dissimulation applied by its members, which presupposed the existence of two parallel programmes and repertoires, led to dire consequences. Between 15 and 18 July 1970, Noroc gave a series of concerts in Odessa, a city where it had performed before and where it had received a particularly warm reception. The concerts took place in the city’s central park, at the Summer Theatre. Inspired by its recent success at the Slovak music festival Bratislavska Lira, the band unleashed a frenzied and violent reaction on the part of the Odessa audience, which included a number of “Soviet-style hippies” and other “marginal” elements representative for underground youth subculture. In its enthusiasm, the mob yelled, smashed seats and ultimately set the Summer Theatre on fire. These events, which were reminiscent of a Western rock festival, placed the party authorities on high alert. The Odessa party secretary, Ovcharenko, remarked that Noroc had “provoked the discontent of socially active citizens and of the vast majority of the audience” even during its previous performances. This time, however, things had apparently got much worse: “Its recent performances provoked a particularly unhealthy agitation among a certain part of our youth, mostly among fans of ultra-fashionable foreign jazz music.” Ovcharenko then harshly condemned “the ideological and artistic quality” of Noroc’s performance, which he found “vulgar and low-brow” [nizkoprobnaia]. He also questioned the group’s professionalism, since, in his view, the band displayed a “lack of any elementary musical culture.” Ovcharenko’s decision was rather harsh, demonstrating the genuine alarm of the Soviet authorities: “it is henceforth prohibited for the Odessa Philharmonic Orchestra to plan” Noroc’s concerts in Odessa. The band was thus effectively banned from the city. In conclusion, Ovcharenko expressed his wish to see another kind of Moldavian music, one that would exhibit “a vivid, professional form and a higher ideological and artistic level.” This attack by the Odessa party officials was coupled with a press campaign in the local newspapers in Odessa and Vinnitsa (another Ukrainian city where Noroc had performed that summer). Several letters from angry members of the audience blasted the band for its Western style and “un-Soviet” behaviour on stage. The letter from Odessa seems to have been the main argument behind the official decision to dissolve the band in September 1970. The members of Noroc were informed about their fate by the director of the Moldavian Philharmonic Orchestra, Alexandru Fedco, on 10 September 1970. However, the official decision was only issued on 16 September. The order of the minister of culture of the Moldavian SSR, Leonid Culiuc, approved by the head of the Cultural Section of the Central Committee of the CPM, Pleshko, mentioned the “frequent complaints of the public” as the ostensible reason for Noroc’s suppression. The band was purportedly dissolved for “gross violations of repertoire policy” and for transgressions of “the norms of artists’ behaviour on stage, which are in contradiction with the tasks of our youth’s communist education.” The authorities thus recognised the subversive character of Noroc’s music and, by implication, of the lifestyle it represented. Even despite the intentions of the musicians, the regime construed any deviation from the accepted cultural and social norms as a threat to be addressed and removed as soon as possible. There are obvious parallels between the musical field and similar tendencies in Moldavian literature and film, where any intimations of “Western” influence became a target for official crackdown in the early 1970s. Noroc’s emblematic musical hits were effectively banned until the Perestroika period, while its members had to find new formats for their careers. The phenomenon of “Moldavian rock” epitomised by these musicians remained, however, significant as an anticipation of things to come.