Phoenix was not only among the most popular rock bands in communist Romania, but also one of the most original, as it pioneered the style called ethno-rock. Established in 1961 in Timișoara as a truly multicultural band comprising members from different ethno-cultural groups, in 1962 the band took the name Phoenix and turned it into a legend of rock in communist Romania. After competing for years with the Bucharest-based band Sfinx to win contests of popularity among the public interested in alternative musical genres, Phoenix put an abrupt end to its Romanian career in 1977, when the members of the band (except for one) clandestinely left the country. The emigration not only provoked their immediate official banning, but also conferred on Phoenix a privileged status in the (semi-)clandestine world of Romanian rock: while their albums could be found only at very high prices on the black market, merely listening to their music became an act of implicit cultural opposition and the band itself an icon above any competition.

According to Béla Kamocsa, one of the founding members, Phoenix took inspiration initially from the subculture of the younger generation on the other side of the Iron Curtain: “The entire generation of young people, intellectuals of the new wave, looked towards the West, towards the artistic world that existed there. (…) It was a time when even in our country there circulated all sorts of books and all those cinematic narratives – Blowup, Z, The Day the Fish Came Out, This Sporting Life – which had as main characters young people who were not at all obedient, but furious, protesting, quite roughly; it is from them that we claimed our roots.” After a first beat period in the 1960s, when the band mostly sang adaptations of musical pieces from the repertories of famous Western bands, such as The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, Phoenix tried to experiment with new styles, pushed partially by the loss of its popular soloist Moni (Florin) Bordeianu, who emigrated to the United States and thus triggered the temporary banning of the band. His farewell concert took place in December 1969, on the occasion of the first Festival of Club A, at that time a recently-founded club of Bucharest-based students of architecture, which would go on function during the entire communist period as a veritable platform for underground concerts. After a short blues period in the early 1970s, Phoenix stabilised its membership and definitively changed its musical identity by the end of 1971.

Paradoxically enough, the members of the band, in particular the leader Nicu Covaci, were able to seize the opportunity to turn to their advantage the hostile new context announced by Ceaușescu’s Theses of July 1971, which reinforced the ideological control of the Party over culture and reoriented all cultural creations in communist Romania towards local sources of inspiration. After 1971, Phoenix created the so-called ethno-rock style by collaborating with the Institute of Ethnography and Folklore and the University of Timișoara with the purpose of discovering genuinely old traditions. Rejecting the kitsch peasant music which was heavily promoted by the official mass media, Phoenix went back to pre-Christian mythology and archaic folklore to find inspiration. Moreover, they created an original synthesis between old music related to ancestral rituals and the modern instrumentation typical of rock music.

This new style was promoted all across the country in series of very successful concerts in student clubs. Eventually, after censorship had eliminated approximately half of the pieces, Phoenix managed to record their first LP, which Electrecord, the only recording company in communist Romania, issued in 1972 under the title Cei ce ne-au dat nume (Those who gave us a name). This vinyl disc changed the status of the band, which was allowed to travel to international festivals in other communist countries and to participate in important national rock concerts. Famous to this day is the joint concert of 19 November 1973 that united the two rival bands Phoenix and Sfinx in the main concert hall of Bucharest, the Palace Hall. Those who could not find a ticket had to face the violence of the Militia, which tried to stop their desperate attempt to enter the concert hall. On this occasion, Phoenix presented some new pieces, which were performed with the help of traditional musical instruments, such as recorder, flute, pipe, and dulcimer, and were based on texts written by arguably the most gifted poets in Timișoara, Andrei Ujică and Şerban Foarță. The concert was so successful that Electrecord immediately invited them to record a new LP, which was issued in 1974 under the name Muguri de Fluier (Flute buds) and instantly became a hit.

In 1973–1975, Phoenix was rated the best band in almost all the opinion polls organised by the Romanian magazines which were popular with the fans of alternative music. The band continued to have an ambiguous position in relation to the communist authorities, in spite of apparently adapting to the official policies in the field of culture and adopting local sources of inspiration. For instance, in 1974, a major Phoenix concert took place at the site of a Dacian mountain fortress, in a highly inaccessible place, which is today a UNESCO protected site as it represents the remains of a disappeared civilisation, but was hardly a tourist attraction at that time, when no guide mentioned it. However, Ceaușescu’s regime heavily promoted the myth of origins according to which the Romanians are direct descendants of the ancient Dacians, because this proved their continuity since Antiquity on the territory of the modern state and their prior claim as inhabitants of this geographical space as compared to the ethno-cultural groups which arrived later, in particular the Hungarians, with whom Romanian historical primacy in Transylvania has been disputed since the nineteenth century. No other band organised such a concert in a place that should have been considered by the communist regime an exceptional lieu de mémoire (site of memory), given the importance conferred on the Dacians in the national historical narrative. Nevertheless, this concert was never broadcast by the Romanian TV, although it was recorded. The climax of Phoenix’s career in communist Romania occurred with the release of the 1975 double LP (the first ever in Romania), which was issued under the erroneous title Cantofabule (instead of Cantafabule). This album represented their work of artistic maturity and registered an enormous success: according to their own estimations, 500,000 copies were sold.

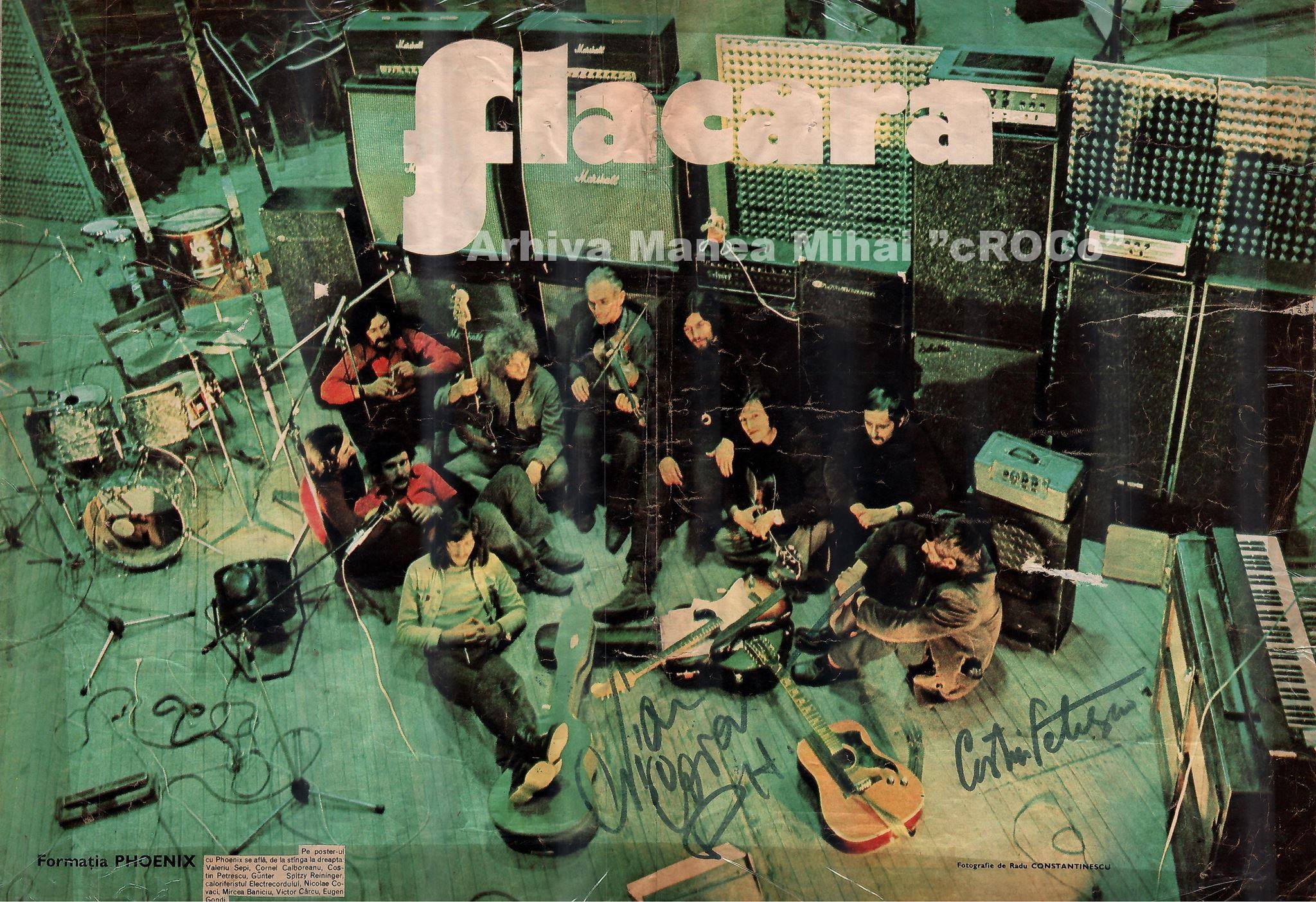

The more popular the band became, the more problems some of its members had with the secret police, the Securitate. Thus, the leader of the band, Nicu Covaci, decided to emigrate, and he accomplished this goal in 1976 by marrying a Dutch national. A year later, he returned with aid for the people in need after the devastating earthquake of 4 March 1977, and took advantage of this visit to help other members of the band to clandestinely cross the border, hidden in loudspeaker boxes. With difficulty, Phoenix continued an artistic career in the Federal Republic of Germany under the name Transylvania Phoenix. After 1990, the band returned to Romania, where it released new albums and gave a number of memorable concerts.