The C.A.D.D.Y. Bulletin collection comprises 106 bulletins, which one could consider as a type of human rights newsletter that aimed to support Yugoslav dissidents. The bulletins in this collection were issued from 1980 to 1992 by The Democracy International’s Committee to Aid Democratic Dissidents in Yugoslavia (C.A.D.D.Y.) based in New York City. The Committee was founded in May 1980 by Mihajlo Mihajlov, a Yugoslav scholar and writer who had to stay in exile in the United States, and other members of The Democracy International, an independent organisation whose stated mission was to assist people who seek democracy in dictatorships throughout the world. The Committee was an active branch of The Democracy International, in which Mihajlov played an important role. The vice-presidents of the Committee at that time were Franjo Tuđman and Milovan Đilas. Apart from publishing, the Committee compiled a list of academic departments and institutions, foundations and professional organisations interested in publishing the writings of or otherwise helping dissidents from Yugoslavia.

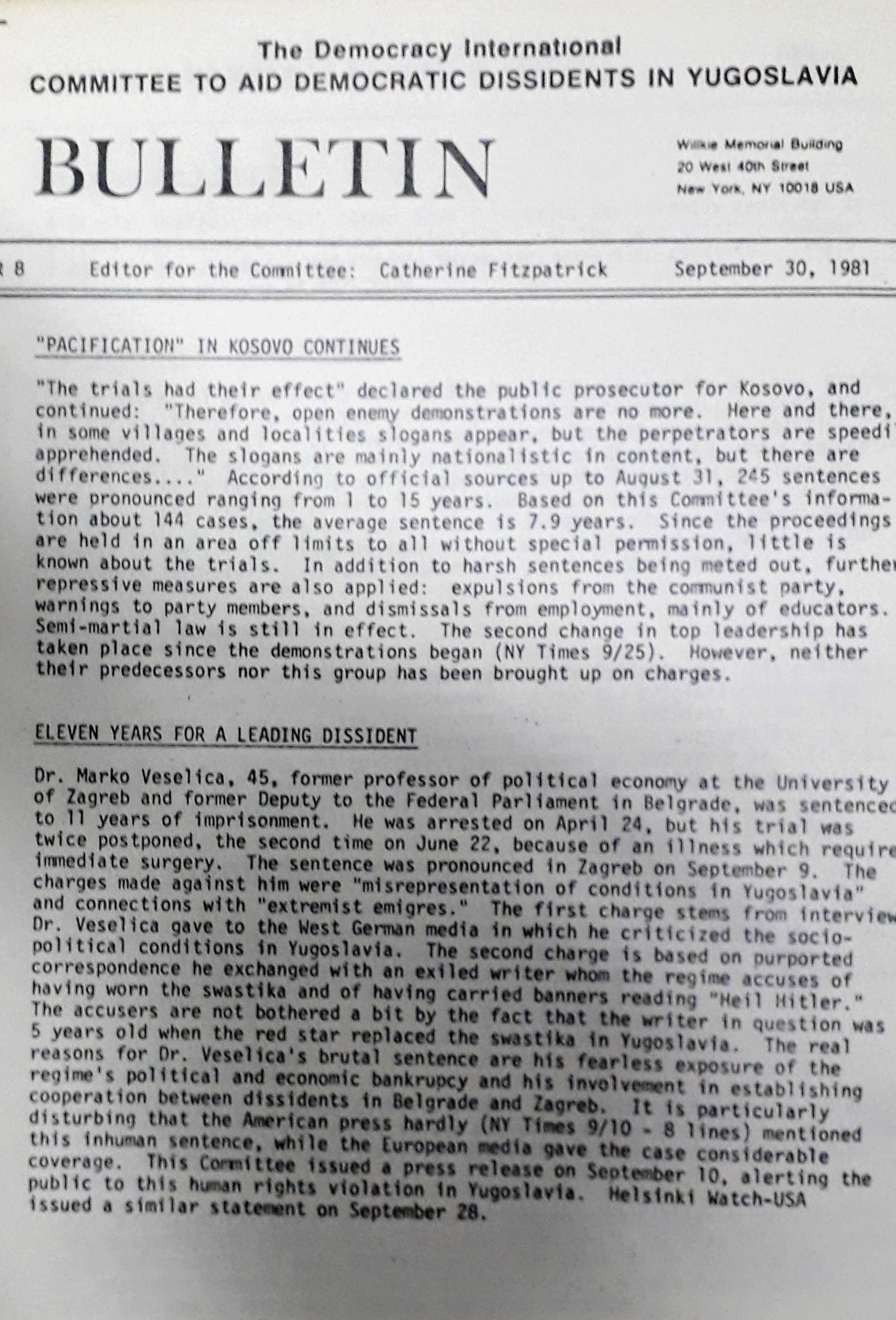

The C.A.D.D.Y. Bulletin was published irregularly. Each issue consisted of reports exhaustively listing cases of repression by the communist regime and information on arrests, trials and petitions concerning Yugoslav dissidents.

The C.A.D.D.Y. Bulletin targeted the Western public (e.g., global human rights networks and organisations such as Amnesty International, journalists and political circles). Given that the West was sympathetic to Tito after the Tito–Stalin split in 1948, Yugoslav dissidents became a sort of scapegoat of the Cold War politics. The C.A.D.D.Y. Bulletin therefore intended to draw the West’s attention to the situation of Yugoslav dissidents by pointing out the large amount of persecution taking place in Yugoslavia. Thus, the bulletins were written in English.

C.A.D.D.Y. Bulletin was established in the 1980s, at the time when the Yugoslav dissident movement was booming. Immediately following Tito’s death in May 1980, this period was marked by progressive liberalisation in some areas but also the deepening of political and economic crises. After the authority of the Yugoslav regime, personalised by the late president, was removed, a phase of political uncertainty began. Due to the struggle of the communist leadership to maintain a degree of legitimacy within their communities, the system of repression began to disintegrate. Sentences handed out at political trials were less harsh than they had been, making the regime’s opponents less fearful. At the onset of the 1980s, the intellectual opposition, although still timid, resorted to new, more visible forms of protest: various discussions, “protest evenings” and gatherings took place. Over the decade, the intellectual opposition grew in strength and organisation, although it was made up of representatives from across the entire political spectrum – from “New Left” activists, to liberals to nationalists. It resulted in the formation of various committees (such as the Committee for the Protection of Artistic Freedom founded in 1982 and the Committee for the Defence of Freedom of Thought and Expression created in 1984) and independent organisations (such as Solidarity Fund). Their public criticism was, in general, focused on civil rights. However, it also occasionally extended to questioning the ideological impeccability of the Yugoslav Communist Party and thus the very legitimacy of the regime, even calling for the abolition of the one-party system.

Although the liberalisation of the public sphere was set into motion, persecution by the communist regime did not disappear. The most famous examples include the trial of Gojko Đogo, a poet who allegedly insulted Tito through his poems, the trial of Vojislav Šešelj, sentenced to eight years in prison for a series of “counter-revolutionary” activities of nationalist character, and the trial of the “Belgrade Six”, which included six members of an informal dissident group which held discussions and gatherings in private apartments – the so-called “Free University” (a Yugoslav counterpart to the Polish dissident Flying University). These three judicial processes contributed significantly to the formation and strengthening of the intellectual opposition both locally (in Belgrade) and regionally (connecting main Yugoslav centres: Belgrade, Zagreb, Ljubljana, Sarajevo). The above-mentioned trials, alongside many others, were reported concurrently in the C.A.D.D.Y. Bulletin, which aimed at extending “moral and political support to those who are persecuted in Yugoslavia for their views and beliefs” (C.A.D.D.Y. Bulletin 1981, 8: 5).

In 2007, Mihajlo Mihajlov, the founder and one of the authors of the C.A.D.D.Y. Bulletin, donated the collection to Srđan Cvetković, a Serbian historian and expert on Yugoslav dissidents. By handing the collection over to Cvetković, an affiliate of the Institute for Contemporary History, Mihajlov aimed to make the collection available to researchers in the future.

The collection is slated for the digitalisation at the Documentation Center of the Institute for Contemporary History in Belgrade.