The collection comprises two main types of official documents. The first category includes the minutes of several meetings held by the Artistic Council of the Moldavian State Philharmonic Orchestra, which discussed and approved the repertoire and official artistic program of Noroc (Good luck) during 1967–1970. These documents illustrate the constant and vigilant preoccupation of the local cultural and political establishment for ideological conformity and their hostile attitude toward any innovation in style or substance, especially if the latter could be related to “pernicious Western influences.” It appears that censorship in the musical sphere was at least as strong as the similar measures applied in the literary and cinematographic milieu. The second type of documents concerns the final phase of Noroc’s activity (the summer and fall of 1970) and clarifies the direct causes of the banning of the band and its implicit disappearance in September 1970, when it was at the height of its creativity and popularity. The regime was appalled by the “un-Soviet” content and style of Noroc’s music, but even more so by the unpredictable and uncontrollable outbursts of the fans at Noroc’s concerts outside the MSSR, during which the musicians took the liberty of ignoring the officially approved programme and responded to the audience’s demand for contemporary Western rhythms and musical arrangements.

The mid- and late 1960s were a period of relative openness and cultural effervescence in the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic. On the level of everyday practices and general youth subculture, the stiliagi (roughly, the Soviet version of the hippy way of life in the West, mainly displaying unorthodox fashion and hair styles) became increasingly popular. In the musical field, the traditional genres focusing on classical orchestras and folkloric motives were gradually challenged by alternative modern tendencies. The mid-1960s witnessed the first open displays of “beatlemania,” especially within certain groups of young urban intellectuals who became familiar with the newest trends either through the “centre” (i.e., through their direct experience of the thriving youth culture in Moscow or Leningrad) or through listening to Western radio stations (mainly Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty). In the case of the Moldavian SSR, these sources of “musical subversion” were supplemented by Radio Bucharest and, particularly, by the extremely popular musical show launched by Cornel Chiriac under the name Metronom, which became famous in Moldavian intellectual circles. Chiriac was later forced into exile and left for Munich, where he worked at the RFE as the host of the new series of the Metronom musical show, which continued to be successful until his untimely and suspicious death in 1975. It was in this context of cultural transformation that, in late 1966, the director of the Chișinău Philharmonic Orchestra elaborated a project for the creation of the first “modern” band in the MSSR. Following the approval of this project by the Ministry of Culture, before the end of 1966 the future Noroc was already in the process of preparing its first official programme. The new group was officially launched in March 1967. Originally, its sponsors in the Philharmonic Orchestra, as well as its leader, Mihai Dolgan, conceived of the new group as a jazz band. However, soon it became obvious that Noroc was proposing something entirely new in the Moldavian (and general Soviet) context: an unexpected mix between Romanian folkloric themes, original pieces synthesising the local and most recent Western musical trends (mainly rock and beat), and Western musical hits borrowed from the repertoire of British, American, Italian, and French singers popular at that time. The influence of The Beatles (and their British and American epigones) and of a number of Italian pop singers, such as, for example, Marino Marini, seems to have dominated Noroc’s peculiar musical style. However, the group also launched several highly successful songs in Romanian, the most famous being De ce plâng ghitarele (Why the Guitars Cry) and Cântă un artist (An Artist is Singing). Another successful hit, Două manechine (Two Mannequins), a bold attempt to imitate the “psychedelic” style of Jimmy Hendrix, was banned by the authorities for its “subversive” elements, too far removed from the acceptable musical forms tolerated by the Soviet authorities (Poiată 2013, 207–208).

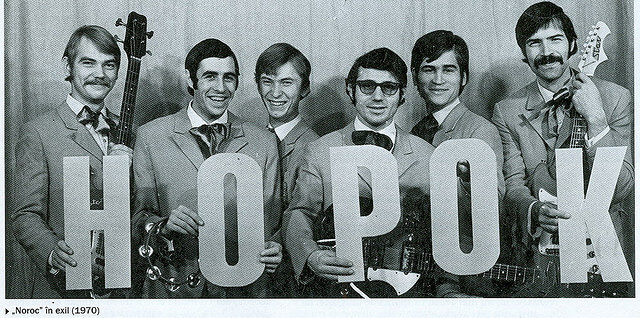

Noroc reached the apex of its popularity in 1968–1970, when it frequently toured various Soviet cities and enjoyed a warm reception from the Soviet public, mainly from young audiences. It was especially popular in Ukraine (particularly in Odessa, Dnepropetrovsk, Vinnitsa, and Kiev) and in Russia, where its unusual style and the fact that it performed mostly in Romanian and the main Western European languages added a touch of exoticism to its programme. According to the accounts of its surviving members, Noroc’s success was also due, to a large extent, to the strategy of dissimulation pursued by the band. While performing in Moldavia, it was forced to abide closely by the approved programme, which included a number of Soviet patriotic songs, folkloric motives and “neutral” musical arrangements in a traditional key. However, during its concerts in other Soviet cities, Noroc performed an “alternative” programme, heavily featuring Western hits and its own musical productions, which received an enthusiastic reception from Russian-language audiences craving for something different. In 1969 and 1970, the band succeeded in recording two vinyl disks (with two original songs each) with the Soviet specialised recording company – Melodiia. Noroc’s success can be assessed by the fact, that the group sold an astonishing 2.5 million disks, which was unprecedented by Soviet standards. During the spring of 1970, Noroc had the opportunity to participate in its only musical festival beyond Soviet borders – Bratislavska lira (Slovakia), where it won the first prize. In the summer of 1970, it looked as if Noroc’s fortunes were at its height. The Moldavian Philharmonic Orchestra, the band’s official employer, was in negotiations with German concert halls (for a projected tour in East Germany and West Berlin) and even Latin American partners. However, two events in the summer of 1970 alerted the Soviet authorities to the covert political message of the band’s Western-style music and to its very real destabilising consequences, thus sealing the band’s fate. The first event was a performance in Odessa in mid-July 1970. Noroc was extremely popular in the city, which also featured a very active community of “Soviet hippies” and a thriving underground culture. During the performance, the audience turned violent, setting fire to the premises of the Summer Theatre, where it was held. It also displayed “unacceptable behaviour” during its enthusiastic reaction to Noroc’s “Western-style” performance. The incidents in Odessa provoked the angry reaction of the city party committee, whose secretary sent an angry letter to Chișinău demanding immediate reprisals and banning the group from Odessa. The second event was linked to the tour of the Romanian band Mondial to Chișinău on 31 August and 1 September 1970, which proved to be extremely popular among young Moldavians, who filled the concert hall to the brim and even shouted “Unification!” (Unire!) during the performance (Stratone 2016, 100). Although Noroc was not directly involved in this project, its members held a number of informal meetings with their Romanian peers. Moreover, the cultural watchdogs noticed alarming similarities between the performing styles of the two bands. In the context of the ongoing campaign against “local nationalism,” this was especially ominous. The Minister of Culture was officially rebuked for allowing Mondial to visit Chișinău and urged (probably by the first secretary of the CPM, Ivan Bodiul, although no direct evidence survives) to act decisively against Noroc. On 10 September 1970, its members were summoned by the Minister of Culture of the MSSR, Leonid Culiuc, and informed that the band was dissolved. The official order to that effect was published six days later, on 16 September 1970. The band’s members attempted to circumvent the system by temporarily moving to the Tambov Philharmonic Orchestra in Central Russia, but after three months an official letter from Chișinău instructed the Tambov Philharmonic to fire the exiled musicians. Noroc’s existence thus definitively ended in December 1970, although part of its former members came together four years later to form another band under Mihai Dolgan’s leadership, Contemporanul (The Contemporary). Although Noroc’s musical style and message was devoid of any open political references or agenda, the significance of this cultural phenomenon can hardly be overstated. It marked an attempt at initiating an unprecedented musical experiment in the Moldavian (and Soviet) context, which aimed at synchronising the local trends with Western mainstream currents while keeping a close connection to the local musical folkloric tradition and heritage. Noroc’s popularity was due to its innovative musical style, but even more so to the perception of its performances in terms of a „musical revolution” and „a musical protest against the Communist regime” (Poiată 2013: 169). This perception was shared both by the audience and by the Soviet authorities, who were quick to grasp the subversive potential of the „imitation of Western bourgeois decadent lifestyles” for the stability of the regime. Although Noroc’s influence should not be exaggerated, their music constructed an alternative social space and a distinctive subculture, breaching the official monopoly on cultural matters. Many of the young intellectuals in the MSSR at the time felt a deep affinity with the tendency toward musical emancipation exhibited by Noroc. Together with similar manifestations in the fields of literature and film making, the ”modernist” trends in the musical sphere in the late 1960s tested the limits of the regime’s tolerance and articulated a radical alternative vision of cultural production deviating from the stifling official canon imposed from above. The Noroc phenomenon was also dangerous to the regime due to its remarkable potential for collective mobilisation. The huge crowds gathering for the band’s performances were perceived as possible hotbeds for unrest and even for fomenting rebellious tendencies among Soviet youth. Besides constructing an alternative cultural space, Noroc was viewed by the authorities as a potential catalyst for a wider political destabilisation of the regime.