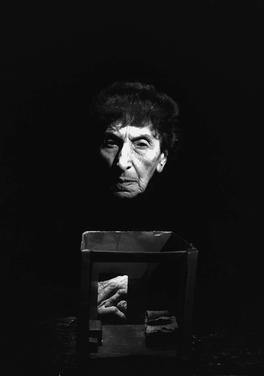

Lena Constante (b. 18 June 1909, Bucharest – d. November 2005) was a visual artist and folklorist, one of the victims of communist repression, and the author of two of the most well-known postcommunist volumes of Romanian prison memoirs, which have been published also in other languages, including French and English. Before the start of the Second World War, she was part of the multidisciplinary teams coordinated and led by Dimitrie Gusti with the aim of producing monographs of Romanian villages. As a member of the Sociological School of Bucharest, Lena Constante had the opportunity to study Romanian folk art in some of the most traditional localities in the country. Stirred by communist ideals, it was natural that she should become close to the intellectual circles at the centre of power after the War. She was a good friend of the wife of Lucreţiu Pătrăşcanu, one of the foremost communist leaders in the first years after the takeover, and contributed together with her to the founding of the first puppet theatre in Romania, the Ţăndărică Theatre in Bucharest. At the same time, her association with this privileged entourage proved dangerous to her. In 1950, she was arrested and implicated in the notorious trial of the so-called “Pătrăşcanu batch.” On the basis of the false testimonies of some members of the “batch,” she was accused, tried, and sentenced in 1954 to twelve years in prison, all of which she served. After this dramatic interval in her life, she married Harry Brauner, who had been her colleague in the teams of monographers coordinated by Dimitrie Gusti in the interwar period and her co-accused in the “Pătrăşcanu batch.” In 1968, as part of a belated process of de-Stalinization, Lena Contante was rehabilitated together with all those implicated in the trial.

After the period of repression, she managed to find her place again professionally, becoming a graphic artist and maker of puppets. With rehabilitation, she received again the right to exhibit the original tapestries for which she had been known already in the interwar period and which again became a success. As a member of the Romanian Union of Visual Artists, she again came into open conflict with the communist authorities in 1974, when she was accused of “destruction of heritage” because she had made tapestries using collages of fragments of old peasant clothes. She managed to defend herself, however, by demonstrating that she had not used items from the heritage of folk costume, but worn-out blouses, bought from or given to her by women in the countryside, who otherwise would have thrown them away or used them as rags for cleaning.

Her longevity as an artist was remarkable. She had exhibitions, both in Romania and abroad, until the last years of her remarkably long life: Lena Constante lived to the age of 96. After the fall of communism, she also published two volumes inspired by her traumatic experience in prison, Evadarea tăcută (The silent escape) and Evadarea imposibilă (The impossible escape), which enjoyed success both in Romania and abroad. Even if she only talks about communist repression, it could nevertheless be said that Lena Constante’s testimony is comparable, in the power with which she evokes the survival of a traumatic episode, with that left by Margarete Buber-Neumann.

She wrote the first book initially in French and published it under the title L'Évasion silencieuse (1990). She then rewrote it completely in Romanian as Evadarea tăcută: 3 000 de zile singură în închisorile din România (1992), and in 1995 it was translated into English as The Silent Escape: Three Thousand Days in Romanian Prisons. In it, Lena Constante states what decided her to contribute to the collective memory of communism in Romania by publishing her prison memoirs: “I want to talk about the state of imprisonment as such. In full knowledge of the facts. Everyday life in a cell. I think I have had a unique experience. A woman, alone, for many years. Years made up of hours, of minutes, of seconds. It is these seconds that I would like to recount, these 3,600 seconds in an hour, these 86,400 seconds in a day, that shuffle slowly along your body, slimy snakes climbing up you from your feet to your neck, without a pause, without mercy, morning to evening and through all too frequent nights of insomnia, one after the other without rest and without stopping, endlessly. Because I want to talk also about human dignity. And about those women, later my prison comrades, who, despite everything and everyone, remained profoundly human beings. And to affirm a hope. The hope that one far-off day, mankind will overcome its nature. Not by changing the courses of rivers, or deserts, or by conquering the cosmos, but by changing itself. Changing its heart and mind” (Constante 1992, 6-7).

These two memoirs are fundamental volumes for an understanding of the communist repression in Romania. Lena Constante received the award of the Romanian Cultural Foundation for “an exceptional destiny in Romanian culture,” and the director Thomas Ciulei dedicated to her an impressive documentary film, Nebunia capetelor (The madness of the heads) (1997).