The backbone of the collection is made up of leaflets pertaining to the 1988–1989 issues of Kiáltó Szó (Screaming word). In order to understand their genesis one must be familiar with Sándor Balázs’s personality and the development of his views from the very beginning until the publication of the samizdat. He grew up as a Székely-Hungarian, though first and foremost as a proletarian in a simple family from Cluj. He very much hated the political system of the time, that is, the royal dictatorship of King Carol II. As Romania underwent gradual changes, he also adapted himself to these. As a result of his parents’ efforts he managed as a proletarian to enrol in the Hungarian-language Bolyai University of Cluj where his professors – among them quite a few “illegalist” communists – implanted in him the belief that “this system we are now building, this system is yours.” And indeed it appeared to be so as he had the possibility of pursuing his academic studies free of charge, and moreover, in his fourth and final year of study he was appointed assistant lecturer (statement of Sándor Balázs).

In an interview dated 1 December 2017, Balázs links the metamorphosis of his personality to the “blows” he was dealt due to the regime. The first blow consisted of the fact that after he got married, it turned out that his wife’s parents were “kulaks.” He became a black sheep as he was married to a class enemy. His professors discussed things with him. One of the professors told him “We, communists need precisely the proletarian intellectual that you happen to be, with a high forehead exactly like mine, but there is a prerequisite to this: divorce your class-enemy wife!” He did not divorce her; they had a child together, and then the situation found an unfortunate solution as his wife succumbed to a cardiac disease at the age of twenty-nine. After his wife’s death Balázs yet again became a major figure of the intellectual proletariat “though the scar was still there” (statement of Sándor Balázs).

His daughter needed a mother so he remarried. This time there were no class differences, but it soon came to light that the brother of his second wife had participated, along with his family, in the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, and consequently had had to defect to the United States. Besides, Balázs had a Székely cousin, somewhat older than himself who had been called up and had been taken prisoner by the Allied forces. Balázs knew nothing about him since they hadn’t maintained close contact; in his biography he writes that his cousin had disappeared in the War. However, the boy had not vanished but had emigrated to America as well. The real surprise was when he came to visit his Romanian relatives, including Balázs. “He came with his big Buick, stopped in front of our house and everybody could see that the American relative, Ferenc Balázs, was here.” Due to his American family members Balázs became a sort of class enemy and yet again a black sheep. This was the second blow he was dealt since it was entered in his file that he had American relatives (statement of Sándor Balázs).

In the fifties it was proposed to him that he should complete his PhD degree studies in the Soviet Union. Together with a colleague he travelled to Bucharest for the entrance examination where he declared that he had no intention of studying abroad. His refusal earned him another black mark. All this had as a consequence that despite his proletarian intellectual status he was not promoted at the university for as long as twenty-six years. He had students who became professors while he still held an inferior position. This led to the situation where “the naïve young man who had become a Marxist eventually became the enemy of the very same social system.” “Luckily” his lectures in philosophy featured subjects that did not require direct ideological commentary; he taught dialectics. One of his students, Gusztáv Molnár, an editor at the Kriterion publishing house who in 1985 organised the Limes Circle, invited him to become a member of this circle. Balázs accepted, pleased to discover that his Marxist lectures had not been so effective after all (statement of Sándor Balázs). Balázs, as the senior member, took an active role in the Limes Circle, a sort of debating club of marginalised Hungarian intellectuals unable to publish their works. This club ensured the public necessary for a minimum echo as well as providing an encouraging community. Balázs was the author of the study entitled Észrevételek és gondolatok Cs. Gyimesi Éva Gyöngy és homok című értekezése kapcsán (Remarks and thoughts about Éva Cs. Gyimesi’s Pearls and Sand) (ACNSAS, I236674/4, 155–172). The meetings always took place in private homes. The last meeting scheduled for 20–22 February 1987 was supposed to be held in Balázs’s Cluj-Napoca home. However, this did not happen because on 7 February 1987 the Securitate conducted a search at the Bucharest residence of Gusztáv Molnár, the leader of the Limes Circle. Molnár had just enough time to call Éva Cs. Gyimesi and her husband Péter Cseke and ask them to notify Balázs about the house search. After being warned, fearing a search himself, Balázs and his wife packed two suitcases full of various documents that had compromising potential, and disposed of these during the night (statement of Sándor Balázs; Balázs 2005).

By the second half of the 1980s the samizdat paper known as Ellenpontok (Counterpoints) of 1982, Éva Cs. Gyimesi’s cultural opposition activity, and the Limes Circle “engaging in illegal discussions” had strengthened civil courage among the Hungarian minority in Romania. However, the suspension of the Limes Circle resulted in a great vacuum. Balázs, who was quite familiar with these occurrences, came up with the idea of filling this void and he suggested that a samizdat paper be launched. He suggested the title Kiáltó Szó (Screaming word), inspired by the 1921 Hungarian pamphlet known as Kiáltó Szó. He saw in the pamphlet an example to follow because after the shock of the Trianon Treaty it was the architect, writer, and politician Károly Kós and his fellows who gave hope to the Hungarians in Romania by saying, “we should be careful, let’s not despair, for we need to take action” and “we can only call our own what we obtain ourselves.” Balázs thought that this idea could be reflected in the samizdat paper. This explains the title Kiáltó Szó (statement of Sándor Balázs).

After discussing the idea with the linguist Éva Cs. Gyimesi, they reached the conclusion that unlike Ellenpontok which had been produced in Oradea, this samizdat should be published in Hungary. After they had managed to establish contact in the autumn of 1987, they found Hungarians willing to support the implementation of the project. Envisaging the possible consequences and the reaction of the Securitate, Balázs elaborated a plan which was the non-plus-ultra of conspiracy. He did not even ask the names of Hungarians who later visited him. They worked out the following scenario for getting in contact. When the young man disguised as a typical backpack-carrying tourist arrived from Hungary, he called Balázs and inquired: Is this the Mátyás residence? Balázs then answered: No, this is the Balázs family. This reassured the inquirer that he was not mistaken and an hour later they met at the statue of Mátyás Corvinus. Balázs made use of three statues in Cluj-Napoca for such meetings, namely: Matthias (Mátyás) Corvinus), Saint George (Szent György / Sfântul Gheorghe), and Michael the Brave (Mihai Viteazul) (Balázs 2005). “I wasn’t daring and courageous. I had another flaw: I was conceited. I was conceited because I had the firm belief, justified as a matter-of-fact, that I was smarter than my persecutors and I wouldn’t be caught. This is conceit in a positive sense and time proved me right since I did not betray anyone, luckily enough,” Balázs said in the interview of 1 December 2017.

The Hungarians offered the editors little financial support, but contributed to the technical side of the operation as they sent Balázs a personal computer of the brand Sinclair ZX Spectrum 48K which counted as quite a rarity in 1987–1988. He connected the PC to the small sports television set that served as a monitor and to the tape recorder that allowed the storage of data. Then he typed in the collected manuscripts on the keyboard. The small-scale device could not memorise more than one and a half lines, therefore the text had to be saved over and over again to the tape. After the entire text had been typed, he encrypted it in its entirety. After encryption the five-page text turned to one paragraph of doodle which became accessible upon entering the code. The tape had to be taken to Hungary. Balázs copied the encrypted material to tapes containing folk songs. He inserted the text into the current song, so that the listener could only hear some chirping and when it was over the song continued. This is how the manuscripts travelled to Hungary, through the intermediary of young men whose names he deliberately omitted to learn. It was a basic rule that one needed to know as little as possible so that if one got caught one could not drag the others in too.

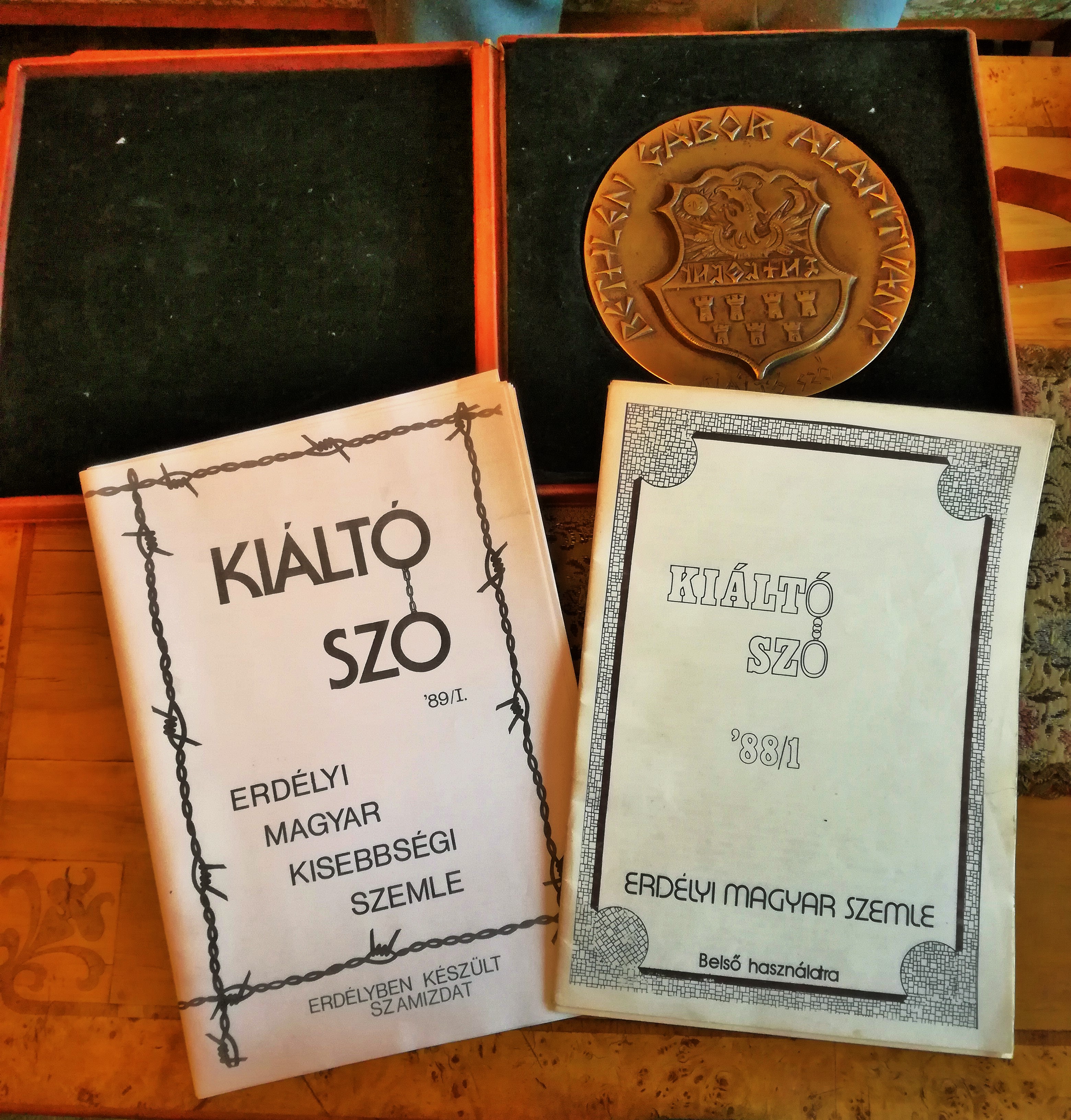

Balázs did not know the Hungarian publishers; he was deliberately guided by ignorance. He did not know who designed the general layout of the samizdat or who transcribed the texts, and nor did he know the editors themselves. After the issues had been printed (only two were published but a further seven issues disappeared), the samizdat material numbering over a thousand copies was returned to Transylvania. Balázs was on good terms with the Hungarian consul in Cluj-Napoca, Emil Popovics, and, since they lived close to each other, they met almost on a daily basis. He discussed the issue with the consul and the Cluj-Napoca consulate agreed to bring the copies back from Hungary, whereas distribution was to be carried out privately by locals. The fact that seven issues were not published can be linked to the closing of the Hungarian consulate in Cluj-Napoca in August 1988. In the spring of 1989, when the second issue was brought into the country, the consulate was still operating; later however, this channel was closed.

Balázs divided the staff of the samizdat into two categories. One group was that of the editors who performed the actual operations, sorted out the manuscripts, translated them, etc. The second category included the so-called external collaborators who simply sent in the manuscripts. The inner team of editors consisted of eight to ten people, for the most part university staff members and journalists. In this respect mention must be made of Éva Cs. Gyimesi and her husband Péter Cseke, Sándor Balázs and his second wife, the philosopher György Nagy, the journalists László Pillich and Árpád Páll, the writer György Beke, and the chemist Róbert Schwartz and his wife Anikó.

The external collaborators included Ágnes Bende Farkas and her husband Sándor, the historian Ernő Fábián, the librarian Tibor Horváth, the journalist Tamás Jakabffy, the literary critic Lajos Kántor, the biologist Zoltán Kiss, the university professor Zoltán Nagy, the politologist Levente Salat, the archivist Gábor Sipos, the linguist Sándor N. Szilágyi, the philosopher Sándor Tóth, and the poet-dramaturge András Visky. Balázs includes also the dissident Doina Cornea and Marius Tabacu in this category. As far as the former was concerned, they translated several of her letters broadcast by Radio Free Europe and also published a personal interview with her. From Marius Tabacu they published a letter addressed to Cornea. Also active in this group were the reporter, radio and TV editor Sándor Csép, the physician Zsolt Mester, who also worked as a writer and was related to Balázs, as well as two Reformed pastors, László Tőkés and his father István Tőkés. László Tőkés wrote about village destruction and his piece was also published, whereas his father discussed the problems pertaining to the Reformed church. Irrespective of confessional adherence, the editors also included the complaints of the Greek Catholic Church in the publication. Apart from the Hungarian–Romanian relationship, they ensured that the German community was also represented through Pillich. The magazine also contained a part dedicated to literature, introduced by Péter Cseke who rendered an analysis of one of István Horváth’s poems (statement of Sándor Balázs; Balázs 2005).

In the period that followed, the Hungarian desk of Radio Free Europe broadcast Kiáltó Szó’s programme-launching article entitled “A Ceaușescu-korszak után” (After the Ceaușescu Era) in which the editors offered a presentation of their views regarding post-dictatorial times. The programme-launching text jointly formulated by the editors stated as a goal the creation of a society functioning in a multi-party system and based on private property. Balázs and his peers did not see the solution in one single political party but preferred democracy. They did not elaborate a party programme and had no intention of forming a political party. They were working on a broader scale, which included political issues, church matters, and also a little literature, among other things. Beyond this, the purpose of the samizdat was the establishment of a dialogue, the elimination of isolation, the presentation of the situation of Hungarians in Romania, and the forging of an alliance with democratically oriented Romanian individuals and groups as far as possibilities allowed (statement of Sándor Balázs).

In 1989 the Bethlen Gábor Foundation in Budapest distinguished the editors of Kiáltó Szó with the Márton Áron Medallion. By offering the medallion from 1988 to persons and institutions in recognition of their outstanding achievements in the service of Christian Hungarians, the foundation wished to perpetuate the memory of the Transylvanian bishop (Márton Áron Medallion 1989). In his published studies in the 1990s Balázs presented the illegal edition published in the last years of the Communist regime and the opposition activity in its background. With his volume entitled Kiáltó Szó: Volt egyszer egy szamizdat (Kiáltó Szó: Once there was a samizdat) presented in 2006 he raised public awareness about the last significant underground manifestation of Transylvanian Hungarian dissidence.