The case of Zaharia Doncev represented an isolated act of defiance against the Soviet regime and was not connected to larger patterns of resistance or group opposition. However, it is revealing because the protagonist was not a representative of the intelligentsia and articulated his criticism rather spontaneously. Doncev was a person of working-class background with incomplete secondary education. At the time of his arrest in December 1956 he was working as an electrician at the meat processing plant (miasokombinat) in Chișinău. However, his family background might have played a role in his critical stance toward the regime. Doncev had two brothers who settled in Romania, while his mother, Maria Doncev, was on the list of people wishing to evacuate to Romania in 1944, which was compiled by the Romanian administration shortly before the Red Army entered Bessarabia in early March 1944. For reasons which remain unclear, she failed to evacuate. Another factor which might explain Doncev’s attitude was his education within the Romanian school system in the late 1930s and early 1940s. He spent a total of eight years in school, seven of them (1936–1940 and 1941-44) in a Romanian educational institution. Although his social origins were humble – he hailed from a family of “poor peasants,” as he emphasised during the inquiry – he was born and educated in Chișinău. The urban environment also might have had an impact on his world view. At some point during the trial, he also confessed that he had a radio receiver, on which he used to listen to foreign radio stations, especially after finishing his military service in the Soviet Army in 1951. Thus, although he understandably insisted on his “healthy” social origins and impeccable credentials as a loyal Soviet citizen, his personal profile was, at best, mixed from the authorities’ point of view. Zaharia Doncev was arrested by the Chişinău KGB on 10 December 1956, and accused of anti-Soviet agitation under Article 54, paragraph 10 (“propaganda or agitation containing appeals towards overthrowing, undermining or weakening Soviet power”), of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR, which at that time extended its jurisdiction over the Moldavian SSR.

Concretely, Doncev’s “crime” consisted in writing and spreading anti-Soviet leaflets. On the night of 18/19 May 1955, he wrote four leaflets with an explicitly “anti-Soviet” content, distributing them on the premises and in the surrounding area of the Chișinău railway station. Three of these leaflets were written in Russian, while the fourth was in Romanian (in Latin script). Apparently, his discontent was triggered by the abuse to which he had been subjected by the police for refusing to pay a fine. In the leaflets, he demanded explicitly the liquidation of Soviet power in Moldavia. He also harshly criticised the Communist Party and predicted an imminent war that would “liberate” Moldavia from the “slavery” of Soviet rule. His message was unmistakably nationalist, with occasional anti-Semitic overtones. He also called for the Moldavian people to rebel against the regime and show their affection for “our beloved Romania,” to which he also referred as “our former fatherland.” Although he talked with admiration about Romania, he did not explicitly call for unification. Rather, he emphasised his desire for the Moldavians to regain their lost dignity and “be masters in their home country.” It is not surprising that on 20 December 1956, after additional questioning at the KGB headquarters, he was also accused of nationalism. Ten days later, on 30 December 1956, the KGB requested that a psychiatric assessment be carried out to decide on the state of health of Zaharia Doncev. This was one of the first cases in the MSSR when punitive psychiatry was taken into consideration as a repressive measure, anticipating the widespread use of this method in the subsequent period. The regime assumed that every Soviet citizen who questioned communism and its alleged progressive nature had mental problems. However, the result was somewhat surprising. The commission of experts concluded that Doncev was in a perfect state of health. Its report stated that the defendant was intelligent, sociable, and very attentive to everything that was happening around him. He apparently liked reading books and playing table games. As for his state of mind while writing and distributing the leaflets, the experts established that he had been aware of his deeds, working at night in order to conceal his actions.

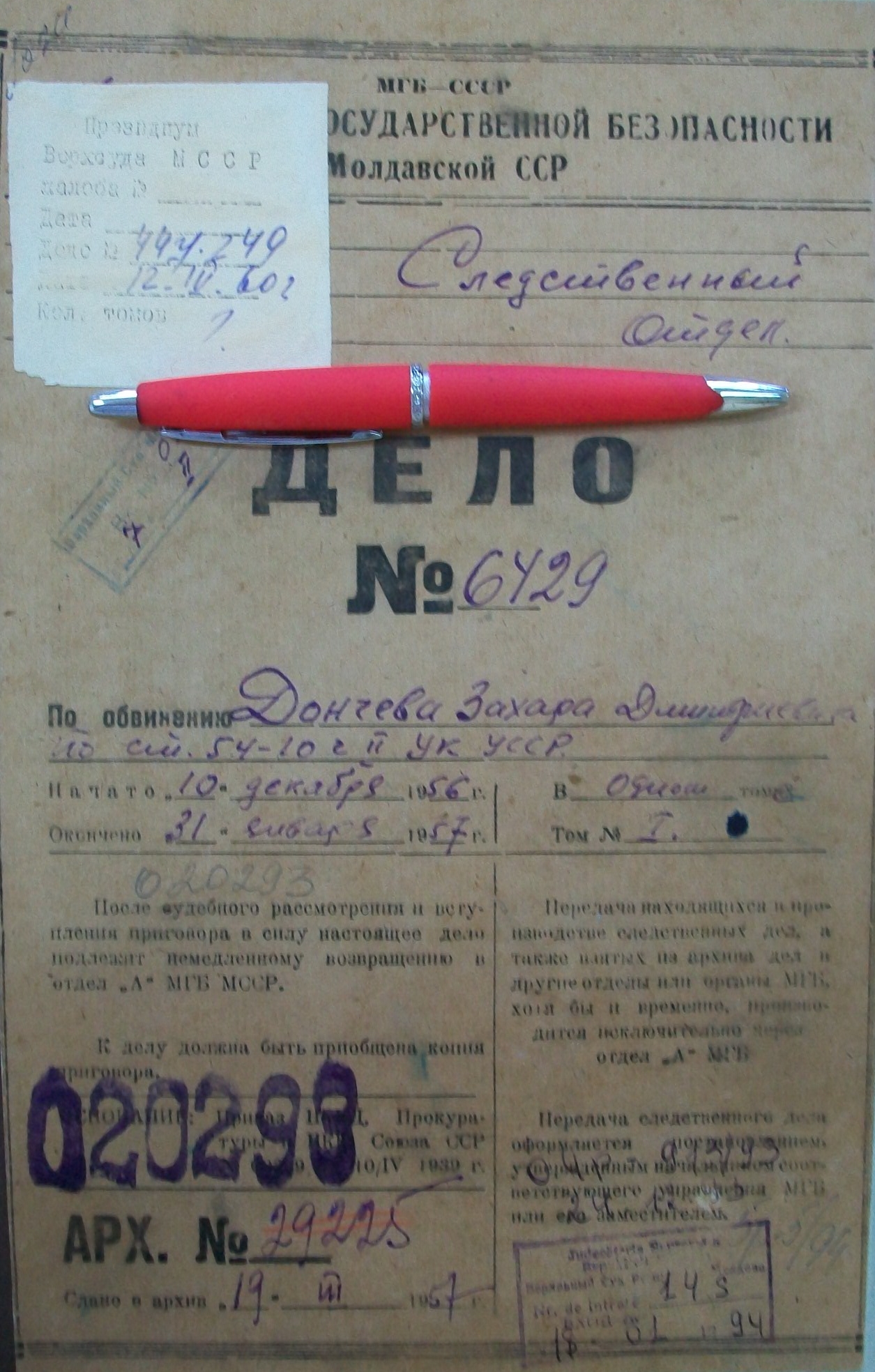

The file on Zaharia Doncev’s case was opened by the Inquiry Section of the KGB on 10 December 1956, and officially closed on 31 January 1957, after the end of the official investigation procedures. It was registered under No. 6429. It is interesting to note that it took the Soviet police and KGB over a year and a half to identify Doncev as the perpetrator, based on expert analysis of the handwriting on the leaflets. Doncev’s one-volume file (amounting to 266 pages) contains the following items: 1) various procedural papers concerning Doncev’s arrest, his transfer to the jurisdiction of the KGB and the search of his house (pp. 1–27); 2) detailed interrogations of the accused, including the concrete circumstances of his actions, his family and professional background (pp. 28–87); 3) interrogations of the four main witnesses, mainly the police officers who discovered the leaflets and reported the case to the KGB, as well as of the railway station employees who identified Doncev (pp. 88–156); 4) various papers characterising Doncev’s professional activity and trustworthiness as a Soviet citizen (pp. 157–162); 5) papers relating to the expertise performed on Doncev’s handwriting, including originals and copies of the leaflets he produced (pp. 163–193); 6) papers concerning Doncev’s mental health, including the conclusions of the medical experts confirming Doncev’s sanity (pp. 194–200); 7) various investigative materials concerning Doncev’s family members (pp. 200–210); 8) the official accusatory act concerning Doncev’s case (pp. 212–215); 9) various papers relating to Doncev’s trial, including the judicial session and the sentence (pp. 216–246); 10) the protest filed by Doncev in January 1960 requesting the reduction of his prison term, the favourable resolution of the Prosecutor General’s Office and the decision of the Supreme Court of the USSR of 4 May 1960 commuting his sentence to four years in prison (pp. 247–260); 11) the appeal and final decision of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Moldova, adopted in April 1994, on Doncev’s final rehabilitation and the annulment of his sentence (pp. 261–266). For the purposes of this collection, the most important documents are those relating to Doncev’s testimony (which he confirmed by his own signature) and the incriminating material evidence collected by the KGB, mainly the copies and originals of the leaflets written by Doncev (in Russian and Romanian).

Doncev’s case is interesting and revealing for several reasons. He was far from a typical dissenter by Soviet standards. Materially, he was well off, receiving a higher wage compared with other social categories. The regime was apparently alarmed by his actions because they had not been provoked by everyday discontent, as in many other cases. It should be noted that Doncev wrote the four leaflets in May 1955, that is, in the early phase of Khrushchev’s Thaw, when the Soviet authorities initiated the first stage of recognising Stalin’s crimes and tacitly rehabilitating the victims of Stalinism. Doncev probably hoped that he would not be punished for his stance as severely as would have been the case under Stalin. As he frequently read the Soviet press and listened to foreign radio stations, he was aware of the tendency of the Soviet authorities in general, and of Nikita Khrushchev personally, to restore a certain “Socialist” legitimacy to the regime and to distance themselves from the Stalinist legacy. However, Doncev’s family background aggravated his situation in the eyes of the Soviet authorities. The fact that his two brothers resided in Romania and that his mother had applied for evacuation to Romania in 1944 were weighty arguments for the authorities to accuse him not only of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda, but also of nationalism. The ethnic and national dimension of the oppositional message was perceived by the regime as much more serious than simple political criticism, especially on the Soviet periphery. Any hint of the Moldavians’ historical, linguistic and cultural proximity to the Romanian nation was seen as potentially dangerous. In another context, Zaharia Doncev’s arrest on 11 December 1956, eight days before the Central Committee of the CPSU adopted a decision to combat anti-Soviet activities, may indicate that the KGB had suggested this idea earlier, while its adoption by the party leadership on 19 December 1956 merely legitimised a practice that had already been applied by the Soviet political police. Zaharia Doncev was sentenced to seven years in prison for anti-Soviet propaganda and agitation and for nationalism, under the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR, Article 54, paragraphs 10 and 2. In January 1960, he filed an official protest requesting a significant reduction of his prison term on the grounds of his loyalty to the regime and exemplary behaviour. The Supreme Court of the USSR approved his request on 4 May 1960. Doncev was legally rehabilitated by the Supreme Court of the Republic of Moldova in April 1994. His sentence was annulled due to the “lack of any criminal component” in his actions.